Abstract

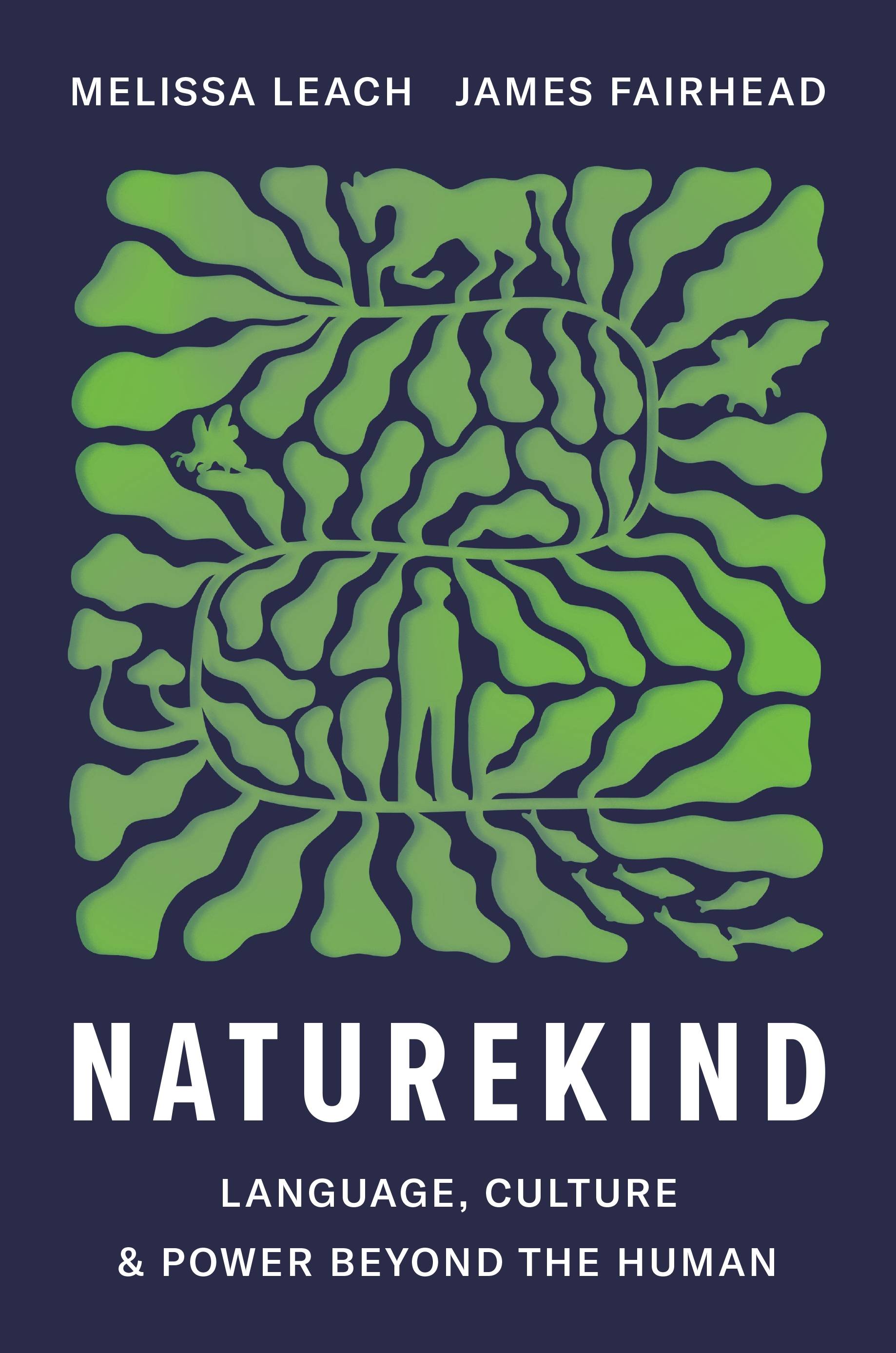

The era in which culture and language can be presumed uniquely human is finally over. Biologists are showing that cultures extend to chimpanzees, but do not stop with primates or mammals, extending too to insects, plants and fungi. The arbitrary meanings of signs and their ordering – languages with symbolism and grammars - are learned by whales, but are also demonstrated right down the phyla. And if language and culture extend beyond the human, so does society itself, so anthropology and other social sciences can no longer peddle human exceptionalism but must reconfigure to embrace interspecies social worlds. Biologists are constrained, however, by the mechanistic ways communication is understood. Drawing on a just-published book (Melissa Leach and James Fairhead, Naturekind, Princeton University Press) this talk explores how this impasse can be addressed by extending insights from structural linguistics, social semiotics, anthropology and Indigenous theorization into wider life, integrating them with new biological findings to develop a novel ‘structural biosemiotics’ paradigm. Illustrations from people’s communicative encounters with both non-human companions and assemblages of living and nonliving entities – focusing here on horses, bats and soils – suggest both a unified theory of meaning-making across all of nature, or “naturekind”, and a set of powerful insights and implications for living well with wider life on a shared planet.