Robert Thomas Ashford: The Life and Legacy of an Unheralded Texas Music Figure

Jaclyn Zapata

Blind Lemon Jefferson is a legendary name in blues history, yet the man who helped secure his first recording remains largely unknown.

Born in Navasota, Texas, on January 2, 1883, Robert Thomas Ashford moved to Dallas in 1910. In 1918, he opened the city’s first Black-owned shoeshine parlor in the Deep Ellum district. When blues recordings gained national popularity in the early 1920s, Ashford seized upon the opportunity afforded to Black entrepreneurs to go into business selling what were known as “race records,” or music sung by and for Black Americans. In 1922, he transitioned the shoeshine parlor into the city’s first Black-owned record store. Through the remainder of the 1920s, Ashford served as a regional talent scout and brought to the attention of northern recording companies many Black artists, including Blind Lemon Jefferson, Willard and Jesse Thomas, and Lillian Glinn. Ashford left Dallas in the early 1930s and went on to become a leading member of the Nation of Islam. This article explores Ashford’s life and contributions to Texas music and the nation’s popular music landscape. It also touches on the emergence of Deep Ellum as an entertainment and cultural district, as well as the use of “race records” as a means of social and cultural uplift for Black Americans.

In 1872, the Houston & Texas Central Railroad reached Dallas, followed a year later by the arrival of the Texas & Pacific Railroad. By the turn of the century, the Missouri-Kansas- Texas, Gulf Colorado & Sante Fe, and the Texas & New Orleans railroads all extended into the city. The introduction of the railroad transformed Dallas into the regional epicenter of trade for cotton and wheat, while connecting larger consumer markets in the east with goods moving from regions to the north, south, and west.1 With the devastation of the boll weevil and decline in the sharecropping system, Dallas became a city of opportunity for Black and white Southerners migrating in search of social and economic advancement in its rapidly growing economy.2 Black men could find employment in construction, transportation, and industrial fields, with convenient access via train to neighboring agricultural areas to work as day laborers.3

Dallas’s population increase lent to the development of the city’s Deep Ellum district, located just east of downtown and encompassing the area near the intersection of Elm Street and Central Avenue. Established in the 1870s as a Freedmen’s town, the railroad helped to define its borders, with the Houston & Texas Central to the west, the Texas & Pacific to the south, and the Texas & New Orleans to the east.4 The railroad brought about an influx of Eastern European Jewish immigrants and Black Americans to Deep Ellum, who played a significant role in shaping its diverse cultural landscape. As described by Alan Govenar and Jay Brakefield:

In the 1870s, soon after the railroads came, the future Deep Ellum was a ragtag collection of pastures, cornfields, cattle and hog pens, restaurants, lodging houses, and saloons. . . The newly settled Eastern European and Black residents quickly transformed Deep Ellum into a thriving business district. Elm Street became lined with predominately white-owned businesses, although they also catered to Black patrons, while Central Avenue was predominantly Black.5

In 1870, Dallas had a population of 2,967.6 Ten years later, it was 10,358. By 1910, the population had jumped to 92,104, of which 18,024 were Black.7

Ashford was among the many Black men in 1910 who relocated their families to Dallas. Prior to his time in the city, Ashford spent his formative years in Navasota working as a farm laborer, where he met his wife, Ruth Richards. Consistent with his timeline, a Robert Ashford first appeared in the 1904-1905 Fort Worth City Directory, working as a Pullman porter, with his residence at 309 South Main Street.8 In the 1905-1906 directory, Ashford is listed as working alongside Sidney S. Shepard at Shepard & Ashford, a tailoring company serving gentlemen’s furnishings, located at 111 East 10th Street.9 By 1907, Ashford’s brother, Ephraim, had joined him in the city, and the two were residing at 1207 East 11th Street.10 It was reported in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in May 1909 that Shepard filed for bankruptcy in June of the previous year.11 By 1910, the Shepard & Ashford tailoring company had ceased operations, and Ashford was no longer listed in the directory.

Ashford and Ruth are first recorded as residents of Dallas in the 1910 Worley’s Directory. His occupation is listed as a tailor at the S.T. Simpson Tailoring Company, located at 406 North Central Avenue, with his residence at 498 Juliette Street.12 From 1912 to 1913, he worked as a porter at the Elks Club before taking a similar role at the Sanger Brothers department store through 1917.13 In an interview with Alan Govenar, Ashford’s daughter Lurline Holland stated that her father established the city’s first Black-owned shoeshine parlor sometime “around the 1920s,” which featured “sixteen chairs, one for each man.”14 Holland’s claim is supported by the 1918 directory, in which Ashford is listed as the owner of a shoeshine parlor located at 408 North Central Avenue, neighboring his former employer, S.T. Simpson.15

By the time Ashford opened his store, Deep Ellum had undergone a major transformation. As its population expanded and businesses flourished, several entertainment venues emerged to serve the Black community. Among the earliest was the Black Elephant Variety Theatre that opened in the 1880s at Young Street and Central Avenue, before relocating to Commerce Street. Others included the Grand Central Theatre on North Central Avenue in the late 1880s, the Standard Theatre on Elm Street in 1908, the Mammoth Theatre on Elm Street in 1914, and the High School Theatre on Cochran in 1915.16 Govenar and Brakefield argue that by 1920, Deep Ellum had established itself as an entertainment district that “paralleled the growth of theatres offering films or high-class vaudeville entertainment, or both, in cities all over the country.”17 These venues would soon become central to Deep Ellum’s identity, fostering a vibrant Black music scene that attracted local, statewide, and national performers.

The national emergence of Black entertainment districts like Deep Ellum in the early twentieth century echoed the rising popularity of music being made by and for Black Americans. A turning point in this history came in 1920, when white vaudeville singer Sophie Tucker was meant to record for OKeh Records in New York. After Tucker was forced to cancel, she was replaced by Black vaudeville singer Mamie Smith. Smith’s recording of “You Can’t Keep a Good Man Down,” sold over 7,500 copies within a month of its release.18 Upon her initial success, Smith was asked back to the studio to record “Crazy Blues,” which sold ten times as many copies than her first release.19 Harlem record stores had trouble keeping copies of Smith’s recordings on their shelves, and Black railway porters began running lucrative business buying up copies for redistribution in the South.20 This led OKeh’s Ralph S. Peer to travel south to investigate.21 What he discovered was that not only could Southern record dealers not meet the demand for Smith’s recordings, but that Black audiences were requesting more songs from Black artists. In response, Peer returned to New York and began recruiting talent for what became known as “race records,” or music sung by Black artists advertised specifically for sale to Black listeners.22 This untapped market prompted other recording companies including Paramount, Columbia, and Black Swan to seek out their own artists to expand their musical catalogs.

Among the 1920s recording companies to enter this newly established market, Black Swan Records stood out as a driving force for music as a means of social and economic uplift for Black Americans. Founded by Harry Pace in Harlem, New York, under the Pace Phonograph Corporation, Black Swan was the nation’s first major Black-owned record label. The label gained national notoriety in 1921, when it signed popular Black recording artist Ethel Waters. Not only did Black Swan push for fair compensation and royalties for its artists, but it also utilized its catalogs as a means of challenging racial musical bias that had taken hold in American popular culture by the 1920s. Karl Hagstrom Miller argues these stereotypes were influenced by early blackface minstrelsy and the American Folklore Society, the latter of which drew from fantasized imagery of Black culture to help define and distinguish “Black music” and “white music.”23 Davis Suisman argues Black Swan aimed to change these stereotypes by expanding beyond simply recording blues, ragtime, and comic records to include operas, spirituals, and classical music.24

Black Swan also echoed the contemporary philosophies of influential Black leader Booker T. Washington. In his 1895 Atlanta Compromise speech, Washington argued the path to racial progress and Black social mobility was through self-determination and vocational training. He urged Black Americans to focus on developing skills in agriculture, industry, and business as a means of achieving long term respect and equality within American society.25 As a leading advocate among 1920s recording companies, Black Swan embodied Washington’s teachings by encouraging Black Americans to strive for economic self-sufficiency by starting their own businesses selling popular music. With this, Black Swan served as more than a recording company, but also as a platform for Black-owned businesses to create tangible social and economic change in the early 20th century.

Ashford was among the Black entrepreneurs who seized upon this business opportunity to sell the latest in popular music recordings. In 1922, he leveraged Deep Ellum’s reputation as a hub for entertainment and transitioned his shoeshine parlor into Dallas’ first Black-owned record store. The store stood at a convenient location across from the Grand Central Theatre, operating at the time as a cinema, and within walking distance to the Negro Theatre Cinema & Vaudeville.26 The store was also located adjacent to the Houston & Texas Central Railroad Platform #4, which allowed convenient access for neighboring musicians and tourists travelling to Deep Ellum for entertainment. In discussing her father’s business, Holland stated,

The store had all the black and white artists - mostly black blues singers - the records, Columbia, Paramount, Okeh - the singers were Ethel Waters, Bessie Smith, Ida Cox, and Sara Martin. In the music shop were three soundproof rooms-called booths or cubicles-to play the Victrola before buying the records. Two or three people could sit in and hear. They always bought three or more records, at the cost of seventy-five cents each.27

One of the earliest advertisements for the record store was listed in the Dallas Express on December 30, 1922. In this advertisement, Ashford played upon the popularity of Black Swan Records and cleverly named the store The Black Swan Record Shop. He would change it in later advertisements to the R.T. Ashford Music Shop.28

Blind Lemon Jefferson had already made a name for himself playing in Deep Ellum’s venues and street corners by the time Ashford opened his record store. Born in Couchman, Texas, in 1893, it is uncertain if Jefferson was visually impaired since birth or if his impairment was brought on by accident or illness in childhood. By the time he was twenty, Jefferson had made a living in Freestone County playing on street corners and at community picnics and parties.29 Around 1912, he left for Dallas to take advantage of its growing opportunities for Black artists to make a living making music. Speaking to Jefferson’s time in Deep Ellum, Ashford’s employee and jazz piano player, Sammy Price, claims Jefferson would “start out from South Dallas about eleven o’clock in the morning and follow the railroad tracks to Deep Ellum, and he’d get to the corner where Central Track crossed Elm about one or two in the afternoon and he’d play guitar and sing until about ten o’clock at night.”30 It was early into Jefferson’s time in Dallas that he met Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, and the two took advantage of the expanded rail system to perform together at establishments across the state.

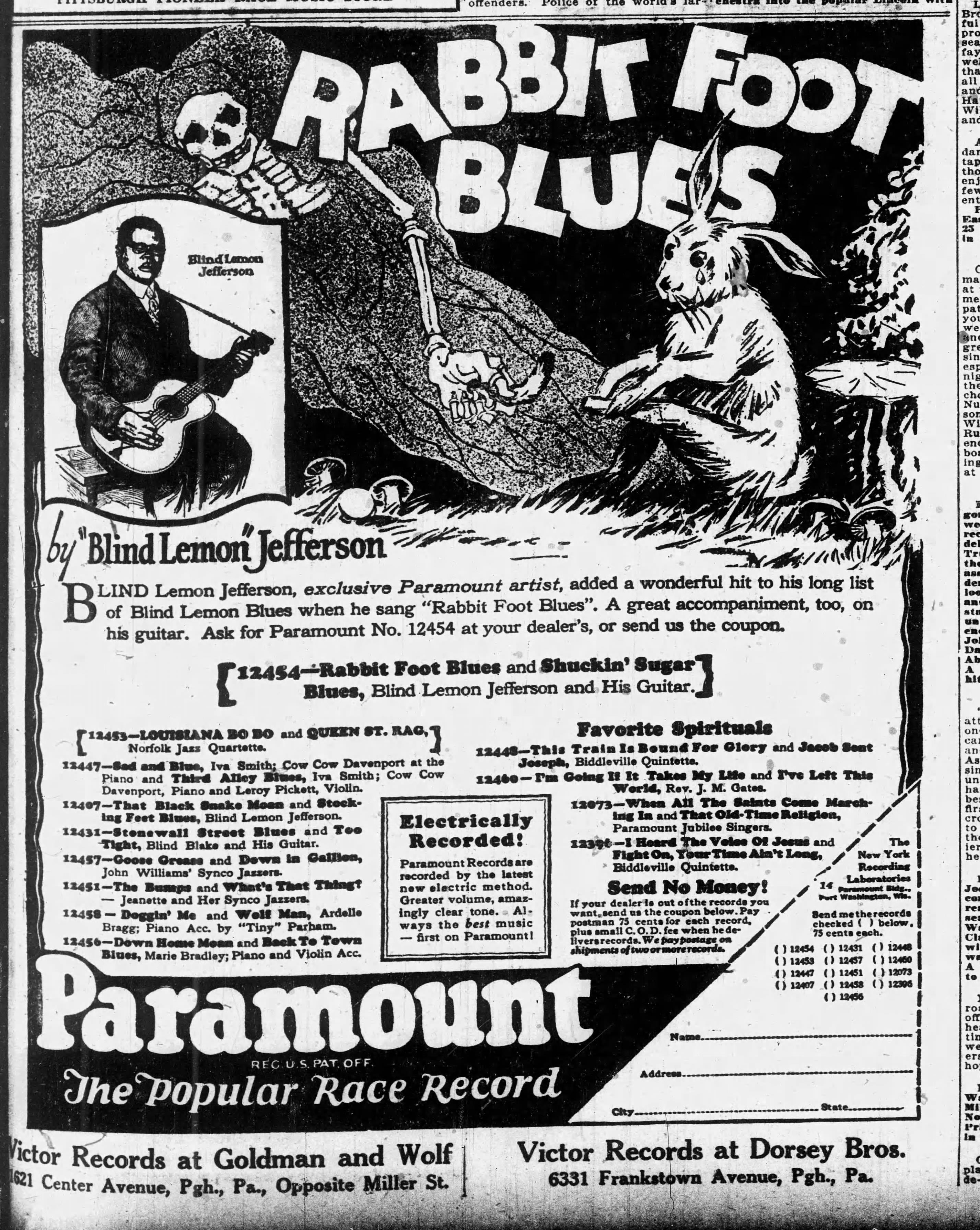

In his autobiography, Price claims he introduced Jefferson to Ashford stating, “Blind Lemon Jefferson had been the first blues singer that I paid attention to, so I went to Mr. Ashford one day and said, ‘You know, Mr. Ashford, I think Blind Lemon Jefferson would sound good on records.’ And he said, ‘Mmmmh.’”31 Elijah Wald argues that Ashford, who was serving at the time as a regional talent scout, then wrote to Paramount’s J. Mayo Williams, manager of the company’s “Race Artists Series,” to see if he might be interested in recording Jefferson.32 As a result, Jefferson received his first recording contract with Paramount in Chicago in 1925, in which Ashford accompanied him.33 Ashford’s assistance in securing Jefferson’s first recording contract led to him becoming one of the most nationally popular male blues recording artists of the 1920s. He recorded over 110 sides throughout this career, including hits “I Want to be Like Jesus in My Heart” and “All I Want is That Pure Religion.”34 Jefferson’s life was cut short in 1929, when he died in Chicago. Historians have disputed the circumstances of his demise, and it was not until his death certificate was found, mistakenly filed under the name George Jefferson, that it was determined he passed on December 19, 1929, from what is listed as “probably chronic myocarditis.”35

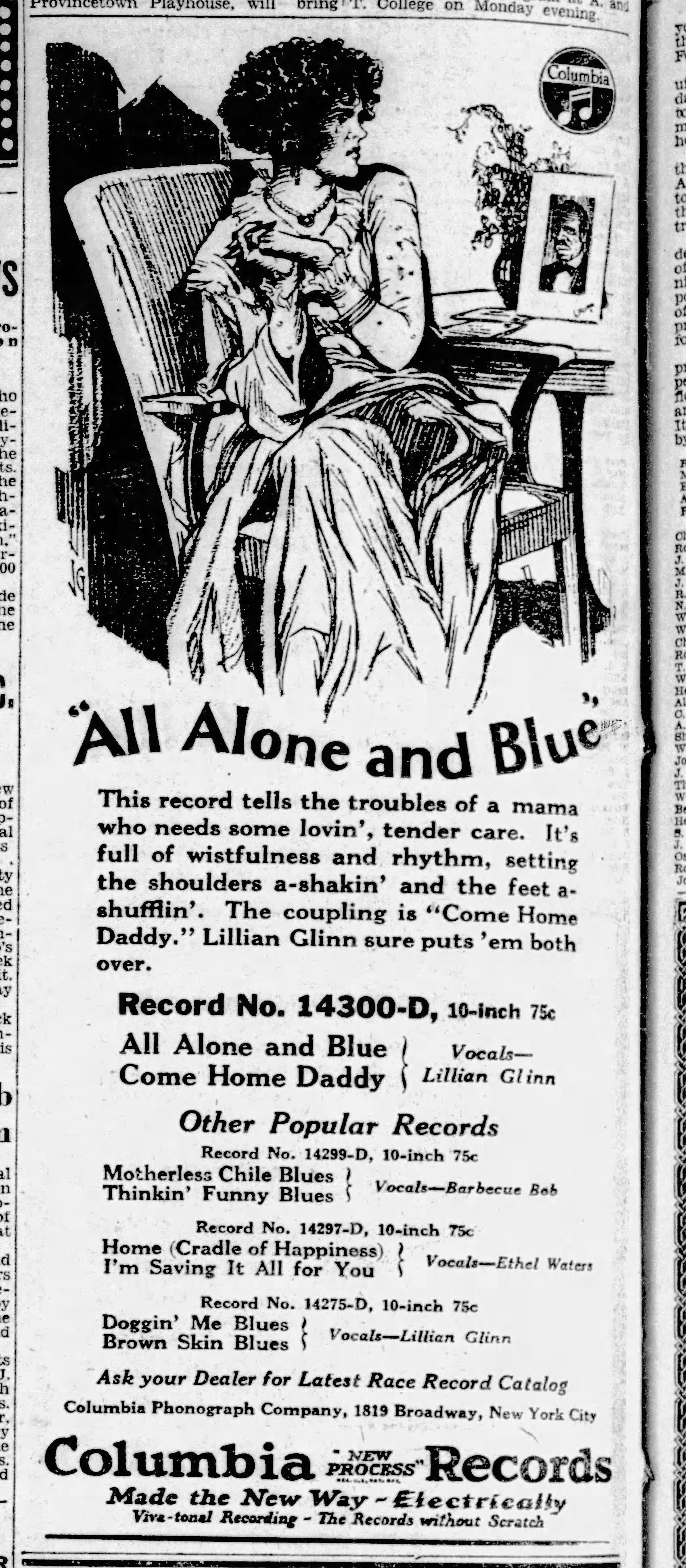

In addition to Jefferson, Ashford promoted and managed Lillian Glinn. Born in Hillsboro, Texas, Glinn was the most famous female blues singer in Dallas in the 1920s.36 Governar and Brakefield argue it was her performance at Dallas’s Park Theatre that led Ashford to take on managing her, helping to negotiate her recording contract with Columbia Records in 1927.37 In an interview with Paul Oliver, Glinn spoke of Ashford’s promotion of her recording “Doggin’ Me Blues”

R.T. Ashford, Mr. Ashford- he had a big record shop. I knowed my record was in ‘cause they done told me it was. I couldn’t get through Central ‘cause there was so many people in there, and when I did get a chance to come in there I just stood, waiting in the crowd to see what they was going. And you know Mr. Ashford just kept on playin’ ‘He’s doggin’ me, and I’m getting’ mighty tired of the way my daddy’s doggin’ me.38

Glinn recorded 22 songs throughout her career with hits including “Cravin’ a Man Blues” and “Shake It Down.” She left the music industry in 1929.

Other artists Ashford helped secure recording contracts for included Louisiana natives and brothers Willard and Jesse Thomas. Willard “Ramblin” Thomas relocated to Deep Ellum in the 1920s, where he met and performed with Jefferson.39 Governar and Brakefield argue it was Willard’s affiliation with Jefferson that most likely introduced him to Ashford. Like he did with Jefferson and Glinn, Ashford helped secure Willard a recording contract with Paramount in Chicago in 1928. Willard would also record for Victor in Dallas in 1932.40 His hits included “Hard to Rule Woman Blues” and “Hard Dallas Blues.” Ashford also helped secure Willard’s younger brother, Jesse “Babyface” Thomas, an audition with Paramount in 1928, although he would go on to record for Victor the following year.41 Jesse would have a longstanding career in the blues until he passed away in August 1995.42 Ashford would continue to promote and manage local and regional artists throughout the 1920s.

By 1932, the R.T. Ashford Music Shop was no longer in operation. Although the circumstances as to why Ashford closed his store are unknown, the economic downturn caused by the Great Depression in 1929 had a profound impact on the music industry. With most families unable to afford luxury items, record sales plummeted, forcing many stores to close. As the country shifted away from leisurely spending, many sought alternative forms of entertainment. The site of Ashford’s record store remained vacant until 1933, when the directory listed it as being occupied by the Radio GospelMissions through 1934.43 The site was once again vacant until 1936, when S.T. Simpson took over the space.44

Holland stated that Ashford left Dallas sometime after 1936 and started a business in Tulsa. He is no longer listed as a Dallas resident in the 1937 directory.46 However, Ashford first appeared in the Polk’s Tulsa City Directory as early as 1932, residing in the city’s historic Greenwood District, indicating he may have moved earlier than suggested.47 It is unclear as to why Ashford moved to Tulsa, although his decision to settle in the Greenwood District was logical, as it had been nationally known as a hub for Black entrepreneurship. In the early 20th century, Greenwood had established itself as predominantly Black cultural and business district, known as the “Negro Wall Street of America” or “Black Wall Street.”48 Most of the district was destroyed in the 1921 Tulsa Massacre, a violent racial attack in which hundreds of Black residents were killed and businesses decimated.

Ashford was among the many Black entrepreneurs who helped reestablish the Greenwood District, operating multiple businesses throughout the 1930s and 1940s. The 1932 directory listed Ashford working in men’s clothing at 123 North Greenwood Avenue.49 By 1936, he is listed as the manager of the Greenwood Haberdashery and residing with Emma Shaw at 323 North Rosedale Avenue.50 In 1942, his draft card recorded him as the manager of the Mid-West Grocery & Market located at 607 East Archer Street, with his residence at 615 East Archer Street.51 An article in the January 1944 issue of the Tulsa Tribune stated that 60-year-old Ashford and 56-year-old Shaw obtained a marriage license the year prior in Sapulpa, Oklahoma.52 It is unclear as to when Ashford left Tulsa, but he is no longer listed in the directory after 1951.53

Following Tulsa, Ashford moved to Chicago where he became a prominent member of the Nation of Islam. A United States Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation report on Wallace Fard Muhammad and the Nation of Islam stated that Ashford, recognized by the alias “R.T.X.,” had served as the minister of Chicago’s Temple #2, also known as Muhammad Mosque #2 or Mosque Maryam.54 The temple was formerly a Greek Orthodox Church before it was purchased by the Nation of Islam and remodeled to serve as a mosque and the organization’s national headquarters.55 During his time as a minister, Ashford became a colleague of Malcolm X.56 He also continued to operate Black-owned businesses, working at the Temple #2 Grocery Store in Chicago alongside Clarence G. Barnes, John Hassan, and Elijah Muhammad’s son, Akbar Muhammad.57 Following Chicago, Ashford moved to San Francisco, where he was a member of the Nation of Islam Temple #26.58 Ashford passed away on June 24, 1976. His obituary in the San Francisco Examiner listed his alias as “Aaron Ali.” He is buried at the Woodlawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Coma, California.59

Ashford’s story is one of the many hidden histories of Black cultural pioneers and advocates who utilized their business acumen to advance Black progress in their communities. Drawing on the philosophies of Booker T. Washington and the Nation of Islam, Ashford sought out and took advantage of opportunities for Black Americans to create social and economic change through self-determination and business ownership. He played a significant role in establishing Deep Ellum as a Black cultural and entertainment district and shaped Texas music and the nation’s popular music landscape by promoting and managing local and regional artists. In December 2024, the Texas Historical Commission erected a State Historical Marker commemorating Ashford’s contribution to Texas music. The marker stands near the site of his record store, located at the corner of Swiss and Central Avenue in Deep Ellum.

Notes

1. Leon J. Rosenberg and Grant M. Davis. “Dallas and Its First Railroad.” Railroad History, no. 135, 40. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43520604 (accessed January 20, 2025).

2. Robert Uzzel, Blind Lemon Jefferson: His Life, His Death, and His Legacy (Austin: Eakin Press, 2002), 20.

3. United Stated Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, “Deep Ellum Historical District.” 2023, Texas Historical Commission, 49.

4. United Stated Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, “Deep Ellum Historical District.” 2023, Texas Historical Commission, 48.

5. Alan Govenar and Jay Brakefield, Deep Ellum: The Other Side of Dallas, (College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2013), 36.

6. Edwin J. Foscue, “The Growth of Dallas from 1850 to 1930,” 16, https://scholar.smu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1053&context=fieldandlab (accessed January 4, 2025).

7. US Census Bureau, “Supplement for Texas: Population, Agriculture, Manufactures, Mines, and Quarries,” 1910, Supplement for Texas, Table II.- Composition and Characteristics of the Population for the State and for Counties. See page 569 for Dallas population from 1880-1910. See page 650 for Dallas’s Black population in 1910. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1910/abstract/supplement-tx-p1.pdf (accessed December 14, 2024).

8. “U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995,” Fort Worth City Directory: 1904-1905, Ancestry.com, 53, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2469/images/4938125?usePUB=true&_phsrc=dIA18&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true&pId=398577083 (accessed November 28, 2024).

9. “U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995,” Fort Worth City Directory: 1905-1906, Ancestry.com, 55, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2469/images/4964461?usePUB=true&_phsrc=dIA18&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true&pId=398577083 (accessed November 28, 2024).

10. “U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995,” Fort Worth City Directory: 1907-1908, Ancestry.com, 93, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2469/images/4966161usePUB=true&_phsrc=dIA18&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true&pId=398577083

11. “Notice in Bankruptcy,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, May 12, 1902, Newspapers.com, 12, https://www.newspapers.com/image/634044851/?match=1&terms=%22Sidney%20Shepard%22 (accessed November 7, 2024).

12. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2469/images/4859237?treeid=&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true&usePUBJs=true&_ga=2.153619128.1848339279.1573934892-1325098692.1564710791&pId=394609776

13. “U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995,” Dallas City Directory: 1912, Ancestry.com, 304. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/406506284:2469?tid=&pid=&queryId=16fd05cca7b29f3e39c26a8e847e3285&_phsrc=WEp15&_phstart=successSource (accessed December 7, 2024).

14. Govenar and Brakefield, Deep Ellum: The Other Side of Dallas, 92.

15. “U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995,” Dallas City Directory: 1918, Ancestry.com, 635, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/1119699679:2469?tid=&pid=&queryId=b69fc36226376ed011e8ea51ae66ec83&_phsrc=WEp24&_phstart=successSource (accessed December 7, 2024).

16. D. Troy Sherrod, Images of America: Historic Dallas Theatres (Arcadia Publishing, 2014), see chapter 3 for information on early segregated Black theatres in Dallas, 49-58.

17. Govenar and Brakefield, Deep Ellum: The Other Side of Dallas, 51-52.

18. Barry Mazor, Ralph Peer and the Making of Popular Roots Music, (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2015), 37.

19. Barry Mazor, Ralph Peer and the Making of Popular Roots Music, 37.

20. Adam Gussow, “‘Shoot Myself a Cop’: Mamie Smith’s ‘Crazy Blues’ as Social Text.” Callaloo 25, no. 1 (2002): 9. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3300383 (accessed January 7, 2025).

21. Barry Mazor, Ralph Peer and the Making of Popular Roots Music, 38.

22. Barry Mazor, Ralph Peer and the Making of Popular Roots Music, 39.

23. Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 41. Miller discusses the influence of early black face minstrelsy and the singing of “coon songs” on Black culture and musical stereotypes on page 41. Miller argue the intersection of academic folklore and the American popular ideas of race, music, and commerce in Chapter 3.

24. David Suisman, “Co-Workers in the Kingdom of Culture: Black Swan Records and the Political Economy of African American Music.” The Journal of American History, vol. 90, no. 4, 2004, pp. 1295–1324. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3660349 (accessed Jan 4, 2025).

25. Louis R. Harlan, ed., The Booker T. Washington Papers, Vol. 3, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1974), 583–587.

26. “Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps- Texas (1877-1922),” Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection, The University of Texas at Austin, University of Texas Libraries, Dallas 1921, Sheet 14, https://maps.lib.utexas.edu/maps/sanborn/d-f/txu-sanborn-dallas-1921-14.jpg (accessed January 7, 2024).

27. Govenar and Brakefield, Deep Ellum: The Other Side of Dallas, Lurline Holland interview with Alan Govenar, May 15, 1999, 92.

28. The Dallas Express (Dallas, Tex.), Vol. 30, No. 10, Ed. 1 Saturday, December 30, 1922, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth278424/m1/2/q=%22black%20swan%22 (accessed February 17, 2025).

29. Uzzel, Blind Lemon Jefferson: His Life, His Death, and His Legacy, 15.

30. Uzzel, Blind Lemon Jefferson: His Life, His Death, and His Legacy, 22.

31. Sammy Price, What Do They Want?: A Jazz Autobiography, edited by Caroline Richmond, chronological discography compiled by Bob Weir (Bayou Press, 1989), 27. It has been disputed if Price or Ashford wrote to Paramount. Price claims that he told Ashford about Jefferson, and that Jefferson then wrote to Paramount.

32. Elijah Wald, Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues (Amistad, 2004), 29. See also citation 34 in which Wald attempts to clarify confusion on whether Price or Ashford wrote to Paramount on Jefferson’s behalf.

33. Govenar and Brakefield, Deep Ellum: The Other Side of Dallas, 92.

34. Alan Govenar, “Jefferson, Blind Lemon,” Handbook of Texas Online, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/jefferson-blind-lemon (accessed February 1, 2025).

35. “George Jefferson,” State of Illinois, Cook County, Chicago, Department of Public Health- Division of Vital Statistics, Standard Certificate of Death.

36. Govenar and Brakefield, Deep Ellum: The Other Side of Dallas, 57.

37. Govenar and Brakefield, Deep Ellum: The Other Side of Dallas, 57-58.

38. Paul Oliver and Mack McCormick, edited by Alan Govenar, The Blues Come to Texas: Paul Oliver and Mack McCormick’s Unfinished Book (College Station: Texas A&M Univ. Press, 2019), 1141.

39. Alan Govenar and Jay Brakefield, Images of America: The Dallas Music Scene 1920s-1960s (Arcadia Publishing, 2014), 32.

40. Govenar and Brakefield, Images of America: The Dallas Music Scene 1920s-1960s, 32.

41. Govenar and Brakefield, Deep Ellum: The Other Side of Dallas, 107.

42. Guido Van Rijn, “Jesse “Babyface” Thomas,” Encyclopedia of the Blues, vol 2, k-z index, edited by Edward Komara (2006), 986.

43. “John F. Worley Directory Co. Dallas City Directory, 1933- 34,” University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, crediting Dallas Public Library, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth806915/m1/1638/?q=ashford (accessed February 2, 2025).

44. “John F. Worley Directory Co. Dallas City Directory, 1936,” University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, crediting Dallas Public Library, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth806921/m1/1539/ (accessed February 17, 2025).

45. Govenar and Brakefield, Deep Ellum: The Other Side of Dallas, 208..

46. “John F. Worley Directory Co. Dallas City Directory, 1937,” University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, crediting Dallas Public Library, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth806912/m1/79/?q=ashford, (accessed February 1, 2025).

47. “U.S. City Directories,” Polk’s Tulsa City Directory: 1932, Tulsa, Oklahoma, Vol. XXIV, Myheritage.com, 49, https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-10705-208926344/robert-t-ashford-in-us-citydirectories#fullscreen (accessed January 7, 2025).

48. Hannibal B. Johnson, “Greenwood: Rebirth,” TulsaPeople.com, March 1, 2021, https://www.tulsapeople.com/city-desk/greenwood-rebirth/article_fed896dc-787c-11eb-9716-2bb94f6d99ac.html (accessed February 22, 2025).

49. “U.S. City Directories,” Polk’s Tulsa City Directory: 1932, Tulsa, Oklahoma, Vol. XXIV, Myheritage.com, 49, https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-10705-208926344/robert-t-ashford-in-us-citydirectories#fullscreen (accessed January 7, 2025).

50. “U.S. City Directories,” Polk’s Tulsa City Directory: 1936, Tulsa, Oklahoma, Myheritage.com, 48, https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-10705-208926319-S/robert-t-ashford-in-us-citydirectories#fullscreen (accessed January 7, 2025).

51. “U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942, Oklahoma,” Robert Thomas Ashford, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1002/images/004139774_00509?usePUB=true&_phsrc=uhD4&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true&_ga=2.48635939.424058123.1572807800-1325098692.1564710791&pId=11959065 (accessed December 7, 2024).

52. “591 Tulsans Wed at Sapulpa,” The Tulsa Tribune, Wednesday, January 12, 1944, 8, Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/image/902425322/match=1&terms=%22Robert%20Ashford%22 (accessed February 3, 2025).

53. “U.S. City Directories,” Polk’s Tulsa City Directory: 1951, Tulsa, Oklahoma, Myheritage.com, 20, https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-10705-208926346-S/emma-ashford-in-us-citydirectories#fullscreen (accessed January 7, 2025).

54. “FBI Documents on Wallace Fard Muhammad by U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI),” Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/FBI-Wallace-Fard-Muhammad/100-CG-33683/mode/2up?q=ashford (accessed November 3, 2024).

55. “Visiting Hours, Tickets, and History of Mosque Maryam in Chicago,” Audiala. Accessed January 13, 2025. https://audiala.com/en/unitedstates/chicago/mosque-maryam.

56. Govenar and Brakefield, Deep Ellum: The Other Side of Dallas, 208.

57. Vivian Azziez, “Testamony of a Muslim American Pioneer,” Muslim Journal, Chicago, Illinois, 20 April 2018: 7. Accessed via ProQuest, February 16, 2025. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2063294706/FE5445F9E154049PQ/10?sourcetype=Newspapers

58. Govenar and Brakefield, Deep Ellum: The Other Side of Dallas, 208.

59. “Funerals,” The San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco, California, Sunday, June 27, 1976. Newspaperscom. https://www.newspapers.com/image/460632572/?terms=%22ashford%22&match=1 (accessed October 31, 2024).