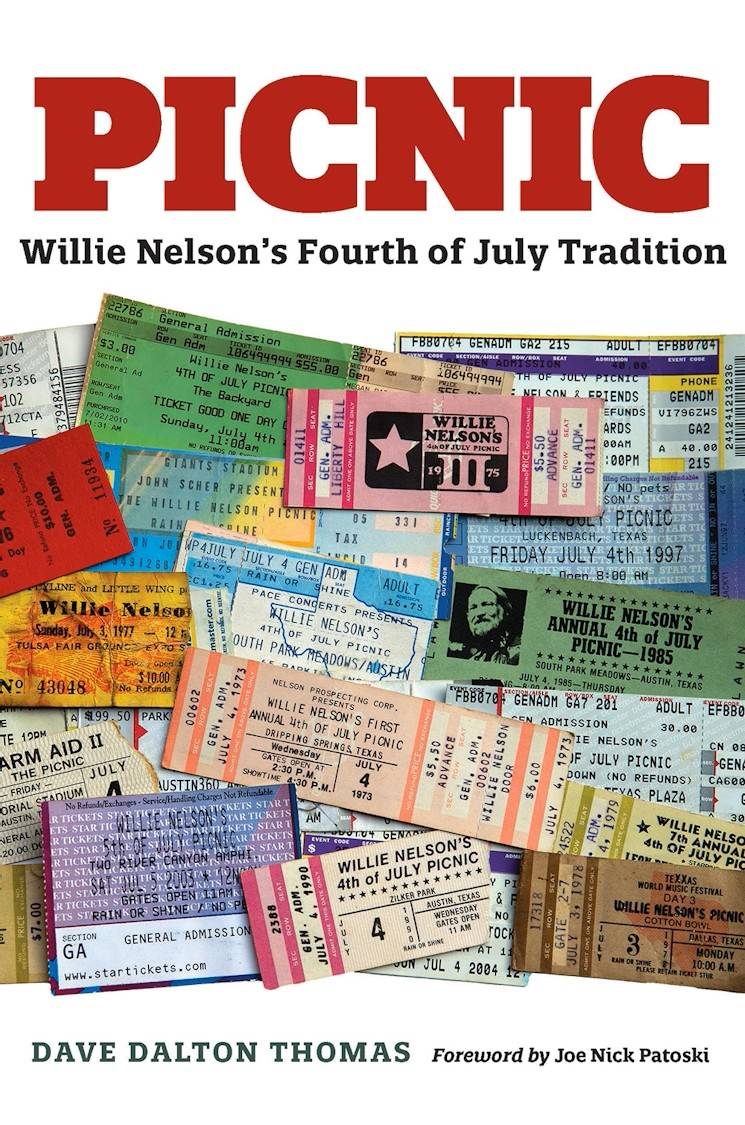

Picnic: Willie Nelson's Fourth of July Tradition

By Dave Dalton Thomas (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2024)

In the pantheon of Willie Nelson literature comes a new staple with Dave Dalton Thomas’s Picnic, detailing the institutional history of Nelson’s own brand of musical “get-together” that’s lasted for over fifty years. The book fittingly begins a foreword by Joe Nick Patoski, exalted Willie Nelson biographer and preeminent cultural guru of Texas. A writer of all things Texas culture and history himself, Thomas manages to trace and illustrate, in breathtaking detail, the chronological lineage of each picnic from 1973 to 2023. While the festival itself has become a kind of living and breathing cultural artifact for Central Texas heritage, his work offers an up-close look at what many may consider a lesser-known part of Nelson’s legacy.

Thomas maintains a straightforward structure throughout the text, with each chapter examining a handful of festival years. While he zeroes in on a few of the picnics at length, Thomas interweaves them with the state of Nelson and friends’ careers, personal lives, and the larger narrative of popular music. The chapters outline years of picnics as they follow the annual tradition’s mission, to present a progressive music festival that showcased Texas-centric sound yet faced the harder realities of fluctuating business models and legal troubles with local government. Thomas makes great use of rarely seen photographs. To see an image of rocker Leon Russell playing alongside Kenneth Threadgill on one page, only to turn a new leaf and find the likes of Doug Sahm, Ray Wylie Hubbard, and Little Joe y La Familia speaks to how Nelson’s picnics were reflective of Texas music’s hybridity. Thomas illustrates multiple perspectives from patrons, lawmakers, and bartenders to musicians and promoters using oral histories and interviews, and provides the lineups and estimated attendance for each picnic along the way. Even for those few years when the festival did not take place, Thomas still gives readers the insider details as to why. Any vantage point relative to the Fourth of July Picnic, he does his due diligence to historicize it.

While some histories of mid-twentieth century Texas music culture often draw hard lines in the sand about the break away from the Nashville sound or the rejection of the creatively stifling machine of popular country music, this work strikes an interesting balance. Thomas acknowledges the uniqueness and mystique of Willie as a cultural icon of Texas music and Americana, but he also centers his storytelling on the idea of the picnics as a literal and figurative landscape of economic, cultural, and regional inclusivity. It was not for “just the hippies and the rednecks, but the working class and the executives, the rural and the urban” were all welcome (236). Thomas succeeds in taking the history of Willie Nelson’s Fourth of July Picnic and framing the event as a deep well of cultural memory.

—Jennifer Ruch Young

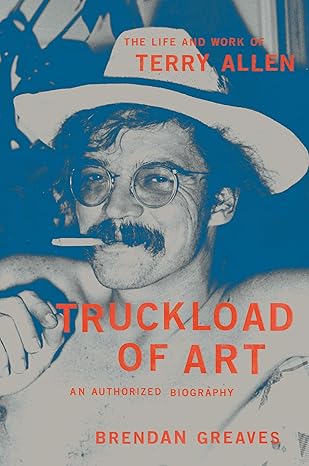

Truckload of Art: The Life and Work of Terry Allen – An Authorized Biography

By Brendan Greaves (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2024)

Terry Allen is a unicorn. Against conventional wisdom, Allen has forged a respectable career that melds music with visual art conjured from stories from the flatlands of the Texas Panhandle. This is highly improbable, although not entirely unheard of, and geniuses who amalgamate often come from parts little known. Robert Rauschenberg, hailing from the swamps of Port Arthur, Texas, comes to mind, but Rauschenberg and others like him did not center their art practice in stories. Allen’s work springs from yarns spun about the places he lived in and the people he cared about.

Allen was born in Lubbock, Texas, just three years before my mother and father were born there, and about three decades before I was. We learn about his birth, his tumultuous and yet enchanting upbringing, his loves, high school hijinks, move to art school in Los Angeles, brushes with Marcel Duchamp, TV appearances, bad and better record deals, domestic fights and reconciliations, many deaths, career struggles and triumphs in a highly detailed, very comprehensive authorized biography by Brendan Greaves, Truckload of Art: The Life and Art of Terry Allen.

The hardback version weighs in at 541 pages. I read and listened to this book from November to April. My mother had fallen desperately ill, and I listened to the book on the way to her apartment, many hospitals, rehabs, and eventually to the hospice care facility where she passed in May. My father also passed the month prior, so as I was finishing this book, I was carrying a heavy load of loss. Greaves’ book and Allen’s life gave my mother and me a lot to talk and laugh about, and I am grateful for that. In full disclosure, this surely colors my review in partisan hues.

Lives are, by nature, complicated, and Allen’s is especially complex. Greaves, who is new to the genre of biography, deliberately employs a circuitous methodology to tell Allen’s story. Greaves’ timeline mostly tracks along a cradle-to-near-present trajectory, but necessarily and admirably details Allen’s artistic and musical practices in a more elliptical pattern, reflecting Allen’s habit of looping back to revisit, augment, expand, and adapt bodies of work such as DUGOUT, Juarez, and Warboy over a period spanning decades. Greaves maps Allen’s life onto three geographic sections, beginning in Lubbock, followed by California, and finally Santa Fe, where Allen currently resides. The Lubbock section provided Mom and me a lot to talk about. She attended his rival high school, her dad played in the same baseball league as Allen’s, and she saw the same UFO that Allen had spied from the rear window of his family’s 1949 Hudson Hornet at the drive-in.

The stories about Allen’s parents are essential and fascinating. His dad was a minor-league baseball player and manager who later turned to music and wrestling promotion, and his mom, Pauline (my mother’s name was Paula), was a hard-living brilliant pianist with a penchant for alcohol, birds, things twinned, and a hazardous habit of kindling several cigarettes around the house at once. As crucial to Allen’s story as his childhood and adolescent escapades are, the art monster in me perked up when he moved to California to attend art school. Allen goes from naming Norman Rockwell as his favorite artist on his Chouinard (now known as Cal Arts) application to meeting Marcel Duchamp. He takes a dare to play “St. Louis Blues” at the Tiffany Club for fifty bucks, and he breathlessly proposes marriage via payphone to a woman he has known from childhood, the inestimable heroine of the book, Jo Harvey. Jo Harvey plays a huge role and is such a towering figure that she deserves a five-hundred-plus-page biography of her own or, perhaps more fittingly, an epic biopic. Allen’s set of charmed circumstances, however, is hard-earned. Greaves provides ample insight into the anxiety, anguish, and ups and downs of Allen’s psyche, physical health, and frequently turbulent relationships. This is heartening and endearing. Greaves paints a portrait of Allen as a multidimensional person, bruised and beautifully complex.

Greaves deploys some purple prose to convey the gnarled highways and byways that inform Allen’s life and art. He betrays his artworld background by using an unnecessarily turgid vocabulary. About a third of the way through, Greaves quotes at length the “marble-mouthed torrent of tortuous clauses” from an early Artforum review of Allen’s work, whose elaborate writing mirrors the author’s own sometimes pedantic voice. This is especially evident in the audio version. I found myself straining through oceans of Greaves’s interpretations of artworks and finding relief in the islands of quotes provided by Terry or Jo Harvey. Thankfully, Greaves’s well-researched book offers an abundance of archipelagos of citations of witticisms and reflections from Allen and Jo Harvey and others, including Dave Hickey, Guy Clark, and Lloyd Maines, that stem the tedious tide of Greaves’ lapses into swollen textual analysis.

The book’s strength lies in the discoveries it reveals. In all honesty, I slept on Allen, which is insane, but typical of artists who track so closely to our own endeavors that we turn a blind eye to them, partially out of hubris but mostly from fear of coming up short. My favorite moments document Allen’s early encounters with Walter Hopps and Dave Hickey. Discovering the radio show, Rawhide and Roses, that Terry and Jo Harvey hosted at a community radio station in Pasadena, a few recordings of which, thanks to Greaves’s record label, Paradise of Bachelors, are preserved on Soundcloud for free, was a revelation. The details of Allen’s songwriting and recording successes and failures were fascinating. I had no idea the barbecue sauce and Austin music venue namesake Christopher B. Stubblefield, aka “Stubb,” was from Lubbock and played such a pivotal role in Texas music. I also learned that an early demo of Allen’s songs was recently released on cassette as Cowboy and the Stranger, and that Allen packaged editions of his album Juarez with a suite of editioned prints, all of which you can see in the archives at Texas Tech University. At Texas State University, where I teach, sitting by the entrance to the Wittliff Collections, which famously combines music history, writerly archives, and photographs, is Allen’s memorial sculpture Caw Caw Blues, dedicated to his friend Guy Clark, with which Greaves begins the book.

This book is long, but it is also one for the ages. Set in ink and in canon are Allen’s fixations, wordplay, rigor, playfulness, singularity, crucial relationships, integrity, irreverence, savvy, stubbornness, anxiety, care, capriciousness, and intuition. This essential book maps the life of a reluctant legend who crafted the stories around him and expressed them in equal measure through art and music. Greaves offers a comprehensive look at a way of being sustained by art through luck, hard work, and connections to the world and the ones we love, and we are so much the better for it.

—Barry Stone