The Making of the Lost Gonzo Band, One of Austin’s Most Essential Musical Groups

Avery Armstrong

Musicologist Travis Stimeling describes Austin’s progressive country music scene in the 1970s as a “Texan renaissance.”1

Participants in the scene actively reconstructed Texan roots to express their desire for a local, self-sustaining cultural scene that encouraged the production of experimental, creative, and anti-commercial music – which, in turn, developed an organic, grassroots music industry built on local talent. Members of one band in particular, the Lost Gonzo Band, would prove to be key players in Austin’s musical revolution.

Though hardly a household name, the Lost Gonzo Band helped to establish the foundation of the modern Austin music scene that has done so much to build the city’s cultural reputation on the national and world stage. While so often only narrowly known for their contributions backing Jerry Jeff Walker and Michael Martin Murphey on albums like ¡Viva Terlingua! and Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir, the Gonzos’ influence on the Texas sound expands far beyond these crucial moments in the state’s music history. Coming from diverse backgrounds, this group of musicians effectively combined their varying expertise to create a unique, hybrid genre of Austin music that became reflective of their own experiences of race, class, gender, and geography during the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War.2 This genre, which would come to be known as “progressive country,” left a lasting impact on the Austin music scene in terms of musical production, recording approaches, and live performance. As a backbone of this movement, the Lost Gonzo Band have remained pillars in the Austin music scene and have been influential in building what is thought of today as the “Live Music Capital of the World.”

This article highlights the lives and musical careers of the members of the Lost Gonzo Band and demonstrates their foundational role in shaping Austin’s cultural image. Through the lens of oral history, my research documents the individual stories of each member of the Lost Gonzo Band. Their personal stories reveal that they privileged authenticity and spontaneity in the live experience over virtuosity or ambition in getting ahead in the music business – ushering in a new era of cultural confluence in Texas’s capital city. This musical approach, coupled with their continued commitment to their local scene, molded the Lost Gonzo Band into fixtures in the city’s cultural history and the larger legacy of Texas music. Coming from a variety of upbringings and musical backgrounds, and migrating from hometowns nationally – and internationally – widespread, this group of kindred musical spirits would change the scope and tenor of Texas music.

Austin’s Live Music Scene: A Brief History

Folksinging – a musical style whose youthful practitioners attempted to recreate a vernacular, precommercial cultural practice – saw a resurgence in national popularity in the 1960s; in Austin, the folk music style set into motion a series of events and collection of ideas that would shape the city’s approach to popular music. Because collegiate folksingers indicated an interest in musical pleasure for its own sake, with no profit or fame involved, historian Barry Shank argues that it created an “aura of authenticity.”3 This musical expression of noncommercialized “authenticity” quickly became a way for countercultural young people in Austin to differentiate themselves from conforming, conservative crowds at the University of Texas.

By the 1960s, Threadgill’s Tavern was arguably the most influential folksinging club in the city and was the genesis of Austin’s local music scene. The venue, previously a Gulf Service station, was owned and operated since 1933 by singer and yodeler Kenneth Threadgill. Threadgill’s hosted open-mic nights on Wednesdays, which packed the small establishment with a skilled, older generation of musicians along with young college students who helped formulate a fledgling singer-songwriter community in Austin. On a national stage, folksingers such as Bob Dylan were starting to inspire youth to question the establishment and authority. In Austin, progressive nonconformists adopted folksinging as a means of communicating a distaste for the commercialization of the music industry – giving way to a burgeoning music scene that emphasized live music, audience engagement, and spontaneity, and challenged listeners to turn away from overly mediated musical experiences and engage with other Austinites in a communal experience that centered around live musical performance.4 In this way, musicologist Travis Stimeling explains that Austin’s burgeoning folk music scene was “the

first direct antecedent of Austin’s progressive country music scene of the 1970s.”5

This pushback began to take shape as young entrepreneurs began to construct new, alternative cultural institutions to serve their own community. The Vulcan Gas Company, for example, emerged in 1967 as a psychedelic rock venue near the center of town and was run by members of the counterculture, for members of the counterculture. The Vulcan actively engaged in the promotion of an anticommercial musical ideology, with house bands such as Shiva’s Headband and the 13th Floor Elevators boldly defining “psychedelic rock” on the Vulcan stage. The venue became a watering hole for Austin residents to reject the commercialization of the music industry. Although lack of business relations (a result of this anti-commercial ideology) and harassment by city authorities caused the Vulcan to fold before very long, it successfully trained individuals who would go on to run prominent local venues in the coming decades. The Vulcan’s noncommercial attitudes and its radical display of difference left a lasting impact on the Austin music scene.

Patrons that once made their home at the Vulcan linked up at other freshly opened venues around town such as the Armadillo World Headquarters. Opening its doors in 1970, venue owner Eddie Wilson claims that the Armadillo ultimately came to be because Austin musicians had few other places to play after the demise of the Vulcan.6 In addition to showcasing local acts, the Armadillo also hosted nationally recognized touring groups. Furthermore, the Armadillo showcased a musically and racially diverse lineup of talent that included acts such as zydeco pioneer Clifton Chenier and blues legends Mance Lipscomb and Lightnin’ Hopkins.7

While venues like the Vulcan and Armadillo World Headquarters were setting the stage for musical revolution in Austin, the city’s image was also being transformed by unbridled economic and population growth, like many other cities in the Sunbelt region – making it a perfect environment for the live music industry to flourish.

“Progressive Country” Enters the Limelight

The Armadillo World Headquarters grew to become the cultural and spiritual epicenter of Austin’s music scene in the 1970s. Local musicians and college students with rural roots intermingled with an overflow of hippie ex-Vulcan patrons and countercultural migrants returning from San Francisco after the Summer of Love. The hippies and rednecks formed a hedonistic coalition of sorts and borrowed from each other’s traditions, giving way to “cosmic cowboys” – who dressed in Wranglers, Stetsons, and boots, but also smoked marijuana, had long hair, and participated in the counterculture. Cosmic cowboys went on to create a new genre of music that would significantly alter the Austin music scene: progressive country music.

“Progressive country”8 was coined in the early 1970s by KOKE-FM, which defined the genre as a radio format. Amid an increasing popularity of country music across the nation, KOKE-FM aided in defining progressive country’s sound. Rusty Bell, KOKE’s disc jockey, believed in a rather loose definition of what country music was; according to Bell, “what mattered was not the identity or hair length or philosophy of the singers, but the kind of instruments that accompanied them. If anything remotely country could be discerned in a recording, it qualified.”9 Progressive country music combined genres such as rock, folk, psychedelia, and blues, but depended on the sounds of traditional country music such as fiddles and steel guitars, a shuffle or two-step rhythm, and harmonized vocals.

This new, eclectic subgenre brought versatile musicians from a variety of backgrounds to work with talented singer-songwriters (mostly individuals from the folk scene, such as Jerry Jeff Walker, Michael Murphey, and Steven Fromholz). These artists, according to Stimeling, would use specific compositions, performance practices, and musical traditions as a catalyst for expressing their individual and collective identities within the Austin music scene.10 Members of the Lost Gonzo Band were central to the development of the Austin sound, the city’s progressive country scene, and the creation of the Live Music Capital of the World. The character snapshots that follow will introduce the members of the Lost Gonzo Band and explore their early musical careers that would lay the foundation for their impact on Texas music.

Humble Beginnings of the Lost Gonzo Band

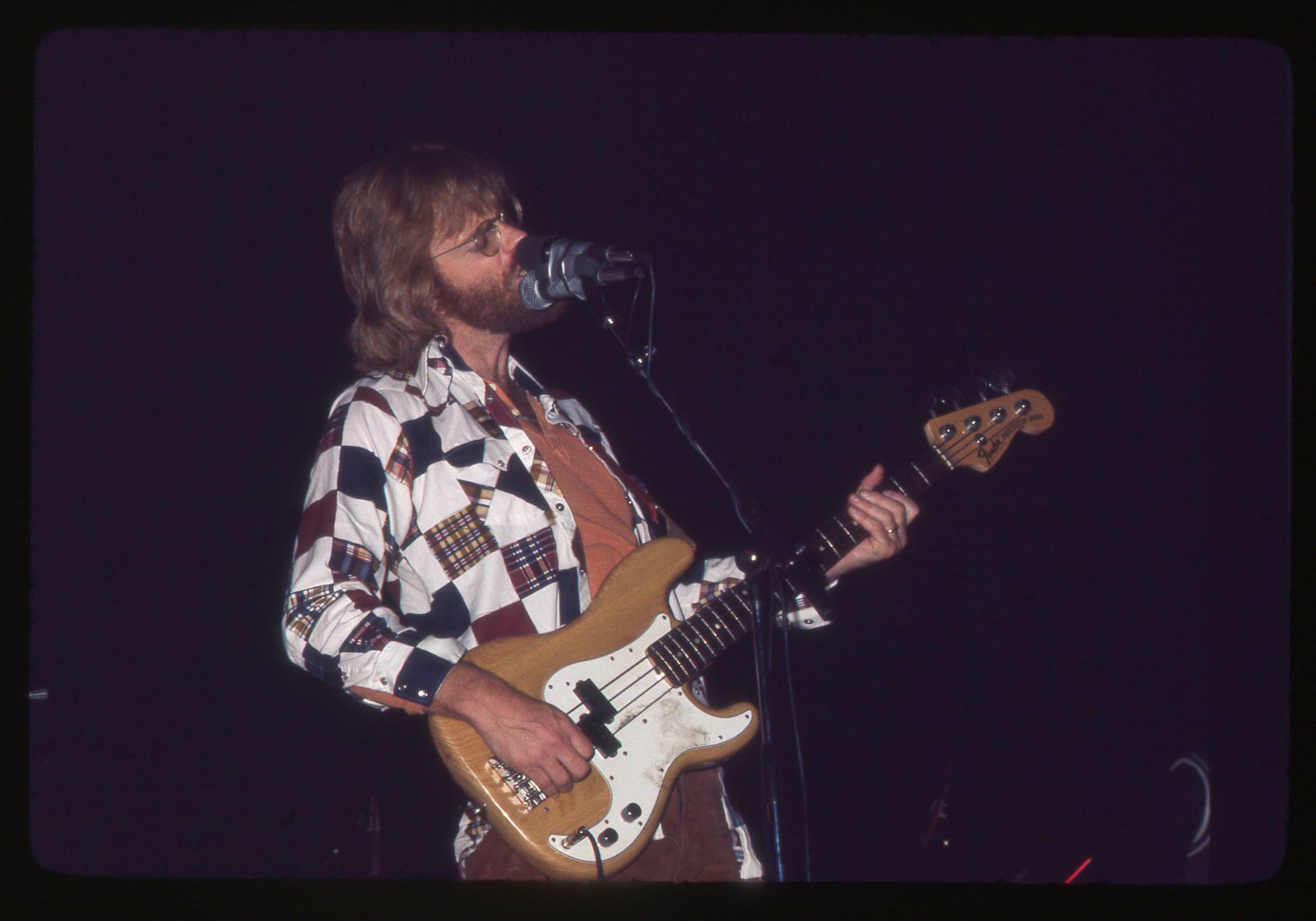

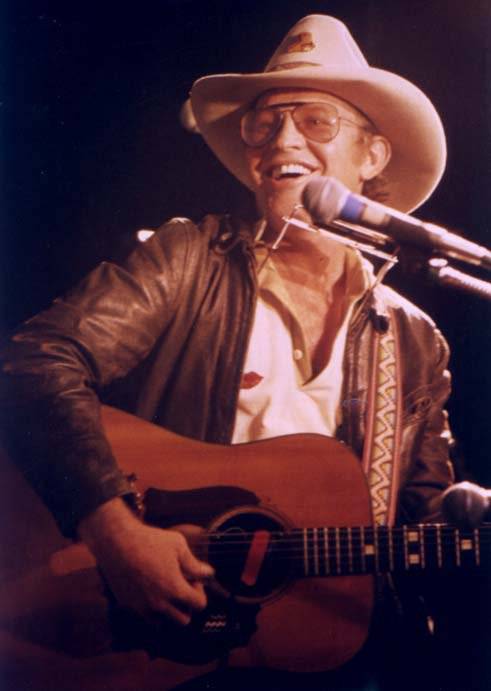

Bob Livingston:

Born in San Antonio in 1948, Robert (Bob) Livingston grew up in Lubbock as the child of two employees of the town’s First United Methodist Church. One night in 1964, a teenage Livingston ventured down to the church’s basement and turned on the television to watch The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show. He recalls that he was struck by the band’s hair, explaining that “in Lubbock, everyone had to have a flat top [haircut] or you would get beat up… The Beatles look[ed] like Davy Crockett!”11 Struck by the band’s musicianship (and their hair), Livingston was inspired to start playing music himself. By the time he reached his teenage years, he was immersed in Lubbock’s music scene.

In junior high, Livingston joined his first band called the “New Grutchley Go-Fastees” – an almost “jug band” who primarily performed at church functions.12 Livingston graduated from Lubbock High School in 1967 – the “Summer of Love” – and enrolled at Texas Tech University. In college, he claims to have convinced a local ice cream shop owner to open up a folk music club in the basement of his store. This compact venue, which ironically became known as “The Attic,” became a regular playing spot for Livingston. In addition to playing at The Attic himself, he also helped in booking other acts there, including Lubbock native Joe Ely, who he calls “Lubbock’s Dylan.”13 Livingston and Ely developed a growing friendship during this time and have remained in the same music circles ever since.

While on summer break from college, Livingston began making annual trips to Red River, New Mexico, playing music at local bars and clubs and driving Jeep tours for extra income. One summer, he made friends with a Dallas band who lived down the street from him called Three Faces West14, who became foundational in developing a folk music scene in the Red River Valley.15 Like all the great folkies on the Western circuit, Dallas singer-songwriter Michael Murphey also played in Red River, and Livingston had seen him there. Although they did not yet know each other personally, Livingston admired Murphey for his poetic songwriting skills and even claimed that Murphey’s songs were “as good as any [he had] heard since The Beatles.”16 After college, Livingston moved to Los Angeles after he was offered a record deal with Capitol Records. He picked up a German hitchhiker one night who said he knew another Texan in California named “Mike Murphey.” In a stroke of luck (or fate), the hitchhiker gave Livingston’s name to Murphey, and Murphey called him that same night.

Livingston teamed up with Murphey and singer-songwriter Guy Clark to form “Mountain Music Farm,” a music publishing venture that was funded by Roger Miller. After recording a number of publishing demos, Murphey invited Livingston to play bass with him on the folk music circuit across the Southwest. Livingston told Murphey that he did not know how to play bass, to which Murphey simply responded, “You’ll learn,” and handed him a Fender Precision Bass.17 This tour with Murphey would be the beginning of a series of experiences that would evolve Livingston’s musical sensibilities.

What started off as a tour of small coffee shops and bars across the Southwest turned into a much bigger, more significant project in Nashville. During their travels, the duo was discovered by producer and fellow Texas native Bob Johnston, who had produced acts such as Bob Dylan, Simon and Garfunkel, Johnny Cash, and other iconic musicians across genres.18 In an interview, Livingston explains that Johnston showed up to the Rubaiyat, a folk club in Dallas, when Murphey’s band was practicing there one afternoon. Murphey was stopped by Johnston’s outcry in the audience after playing the first two lines of “Calico Silver,” a song he wrote about the life and death of the mining town of Calico, California. Johnston exclaimed that the song was the most beautiful thing he had ever heard, and offered Murphey a record deal.

Livingston and Murphey embarked on a journey that would produce one of the founding documents of progressive country music. The duo piled their belongings into a Buick – belonging to Murphey’s mother – and headed off to Columbia Studio A in Nashville to record an album that became known later as Geronimo’s Cadillac.19 In the studio with Johnston, they recorded each song in one or two takes and cut over twenty songs in two days. The album included significant radio hits such as the title track, which was later covered by Cher, “What Am I Doing Hangin’ ‘Round?,” which was recorded by the Monkees, and “Backslider’s Wine,” later popularized by Jerry Jeff Walker and the Lost Gonzo Band on ¡Viva Terlingua!. While they cut the basic songs for the album, they did not finish it completely; recording tracks for Geronimo’s Cadillac would be picked up at a later date by Murphey and a number of other notable Austin musicians.

Livingston openly admits that he was excited yet overwhelmed by Murphey’s talent and drive, claiming that recording with him was like getting “thrown into the deep end of the pool.”20 As the duo rounded out their tour together, tensions started to arise between them. While Livingston was flexible and free-wheeling in his musical approach, Murphey was more structured and polished. Livingston describes Murphey as “exacting” and “a stern taskmaster” in rehearsals and on stage.21 Ultimately, Livingston decided to discontinue working with Murphey because of this difference in musical philosophies. He committed to playing bass again for Three Faces West in New Mexico. Murphey and Livingston’s last gig together for the time being was at the Saxon Pub in Austin, a new singer-songwriter venue that opened following the closing of Rod Kennedy’s Chequered Flag, which had historically been one of the town’s most popular folk music venues on the “Coffee House Circuit.”22 Livingston – who describes himself that night as “totally out of it” and “freaked out to the max” – hopped into his car as soon as the show was over and headed to Denver to meet up with Ray Wylie Hubbard and the rest of the band.23 However, when it was time for Geronimo’s Cadillac to release, Murphey – per Johnston’s insistence – called Livingston and asked him to rejoin the band to tour and promote the album. He obliged, and continued working with Murphey for a few more months after that.

Gary P. Nunn:

Gary P. Nunn grew up in Eram, Oklahoma, a small rural town where both of his parents worked in the school system. His family moved to the Texas panhandle town of Brownfield when Nunn was 12 years old, where he began playing drums in a band he formed with his classmates called The Premiers. When their bass player quit, Nunn took over; he bought a Fender Precision Bass and began his bass playing career that would persist until 1979. Nunn also played basketball and football, and was involved in choir and theater productions throughout high school.

In Nunn’s later high school years, he started playing rhythm guitar with a band called The Sparkles – a garage rock group from Levelland, Texas (which neighbored Brownfield). After graduation, Nunn cancelled plans to go to the University of Texas and enrolled in Texas Tech University, and then South Plains College in Levelland. He was making substantial money with The Sparkles because they were such a well-received band and picked up a large number of gigs. When the band set their sights on bigger things and wanted to move to California, Nunn made the decision to stay in Texas and finish school.24

Picking back up on his previous plans to go to the University of Texas, Nunn moved to Austin in the fall of 1967 to attend pharmacy school, playing a couple of gigs a week with a group called the Georgetown Medical Band. As time went on, he became less interested in school and increasingly infatuated with playing music and performing in the city’s flourishing music scene. Nunn dropped out of school in the fall of 1969 to focus on his music career. He was hired to play organ for a band called the Lavender Hill Express, which was, at the time, the “hottest band in town.”25 The Lavender Hill Express was led by Rusty Wier, who played drums and sang vocals, and also included guitarist Layton DePenning. The band opened for a number of big acts that passed through Austin and were booked at popular clubs, such as The Jade Room and the New Orleans Club, multiple nights a week.

The Lavender Hill Express split up in 1970, but Nunn and DePenning decided to stay together and form another band called Genesee (the name of a Colorado town just west of Denver, and a combination of “genesis” and “Tennessee”). In interviews, both Nunn and Bob Livingston described Genesee as a “frat rat band” – a band that primarily played for fraternities at the University of Texas, but didn’t secure many other gigs.26 The band adopted a folk singer-songwriter sound that mimicked Crosby, Stills, Nash, & Young, and began to primarily write and perform songs of their own. One night at the New Orleans Club, Nunn crossed paths with John Inmon, a skilled and well-known guitarist in the Austin scene. Nunn admired Inmon’s musicianship, taking note of his “extraordinary natural talent and guitar-playing ability,” and asked him to join Genesee.27 Although Genesee eventually disbanded due to disagreements in the band, the relationship between Nunn and Inmon would prove to be important in the coming years, and the band’s shift in sound and songwriting approach would prove fundamental in Nunn’s journey during the next decade and beyond.

One fateful night, Nunn went to see Michael Murphey perform at the Saxon Pub.28 Much like Bob Livingston, Nunn also admired Murphey for the “eclectic, poetic, and intellectual quality of [his] material.”29 Though they had never met, Murphey approached Nunn between sets, as he had heard good things about Nunn and knew of him because of his stints with The Sparkles and the Lavender Hill Express. Murphey asked Nunn to play bass in his band, as his bass player (Livingston) had just quit and moved to New Mexico. Aware of Murphey’s reputation as a prolific songwriter, his recording contract with Bob Johnston, and a new record in the works, Nunn swiftly accepted the offer.

Murphey brought Nunn and the rest of the band (which included Craig Hillis, Herb Steiner, and Michael McGeary) back to Nashville to finish recording Geronimo’s Cadillac. The songs that Murphey previously recorded with Livingston at Columbia Studio A were overdubbed with drums added in, and Murphey asked Nunn to play piano and B-3 Hammond organ on a few tracks. After they finished recording, Murphey and Nunn travelled around Texas together and played gigs in college coffee shop circuits and small bars across the state.

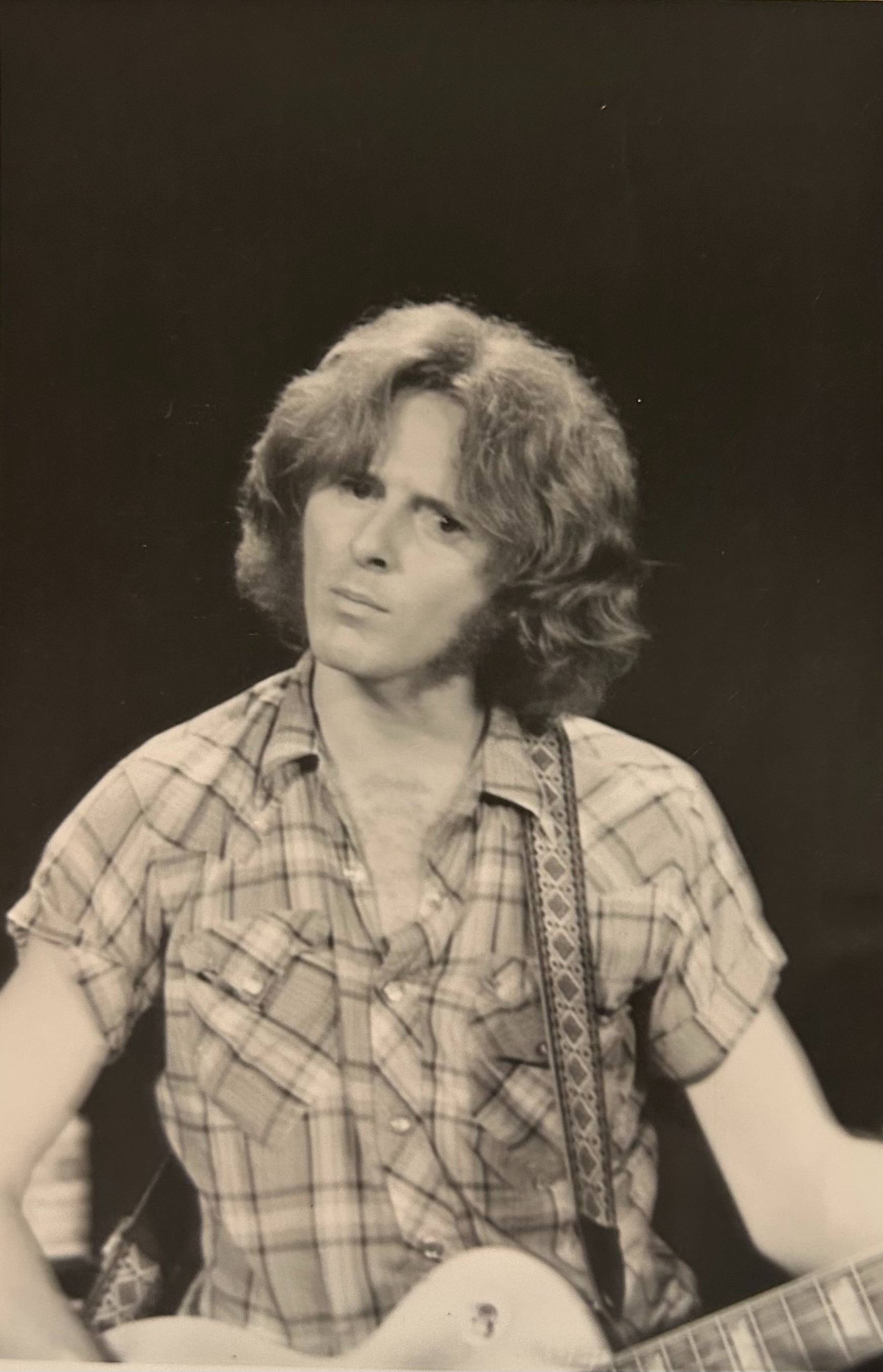

Craig Hillis:

Craig Hillis was raised in a military family and moved around frequently during his childhood. He grew up in a musical household; his father, who was a career Air Force officer, was a musician, as were his grandparents and great-grandparents on his mother’s side.30 His musical interests developed during the years his family spent living in England, where he became inspired by the style and music of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, as he experienced the early impacts of the British Invasion from the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.31

Hillis joked in an interview that after he moved to Washington D.C. in 1963, his grandmother bought him a guitar and “ruined [his] life,” and he’s been “chasing the guitar ever since.”32 He played in rock bands throughout his high school years that he explains, “diligently tried to reproduce the top-ten radio playlists of the era.”33 Hillis got hired at a local music store in Washington D.C. where he worked as a guitar salesman and instructor. In 1967, Hillis enrolled in the University of Texas where he played in “top-forty bands” that performed at local nightclubs and on the University of Texas fraternity sorority circuit. During his fourth year of college in 1970, Hillis dropped out of school and fully dedicated himself to the Austin music scene.

Hillis soon befriended a group of singer-songwriters who came through Austin on their promotional tours. As a part of this group, Hillis would learn skills and have experiences that would help lay a foundation for his musical sensibilities. Two of these renowned singer-songwriters were Steven Fromholz and Dan McCrimmon, who together formed a folk-music duo called Frummox. When Hillis went to see Frummox perform in 1969 at the Chequered Flag, Austin’s premier folk venue, he explains that he experienced an “aesthetic wake-up call;” he was immediately inspired by Fromholz’s songwriting style and vivid lyrics, but also his musicality and ability to produce both “delicate and dynamic melodies.”34 After the show at the Chequered Flag, Hillis was introduced to the Frummox duo and was invited back to a “serious song swapping and party pickin’” session at a hotel; as they passed guitars around that night, a spark grew that kindled a lifelong friendship between Hillis and Fromholz.35

Hillis credits Fromholz in providing him with a preliminary initiation into the world of songwriting. Hillis packed up his Volkswagen hatchback and moved to Denver in 1971 to be closer to his new friend. He joined a band called Timberline Rose and played a “house gig” at a rustic mountain inn to earn steady income.36 After a few months of living in the Denver area, Hillis was introduced to Michael Murphey and Bob Livingston, who were in town to play a four-day booking at a café. Hillis describes Murphey as a prolific, “very technical songwriter” who was well-read and took an academic approach to songwriting.37 They quickly struck up a friendship and spent their time together exchanging songs, stories, and guitar licks. Hillis was asked to play with the duo at the Denver café the following night, and subsequently asked to tour with Murphey as he was promoting his first album, Geronimo’s Cadillac.

Hillis’s rock ‘n’ roll background and his songwriting experience with Fromholz and Murphey set him in a category of his own, bringing a special uniqueness to bands he played with. When he moved back to Austin in 1971 to play fulltime with Murphey, he continued to sharpen his craft and learn more about music and songwriting. During rehearsals and performances with his new band – Murphey, Bob Livingston, Gary Nunn, Herb Steiner, and Michael McGeary – Hillis had “really clever ideas about what to play and when to play,” according to Nunn.38 He was always eager to learn new things, absorb information and experiences, and become the best he could possibly be at his craft. These traits would serve him well as he continued to play with pioneering acts in Austin’s progressive country music scene.

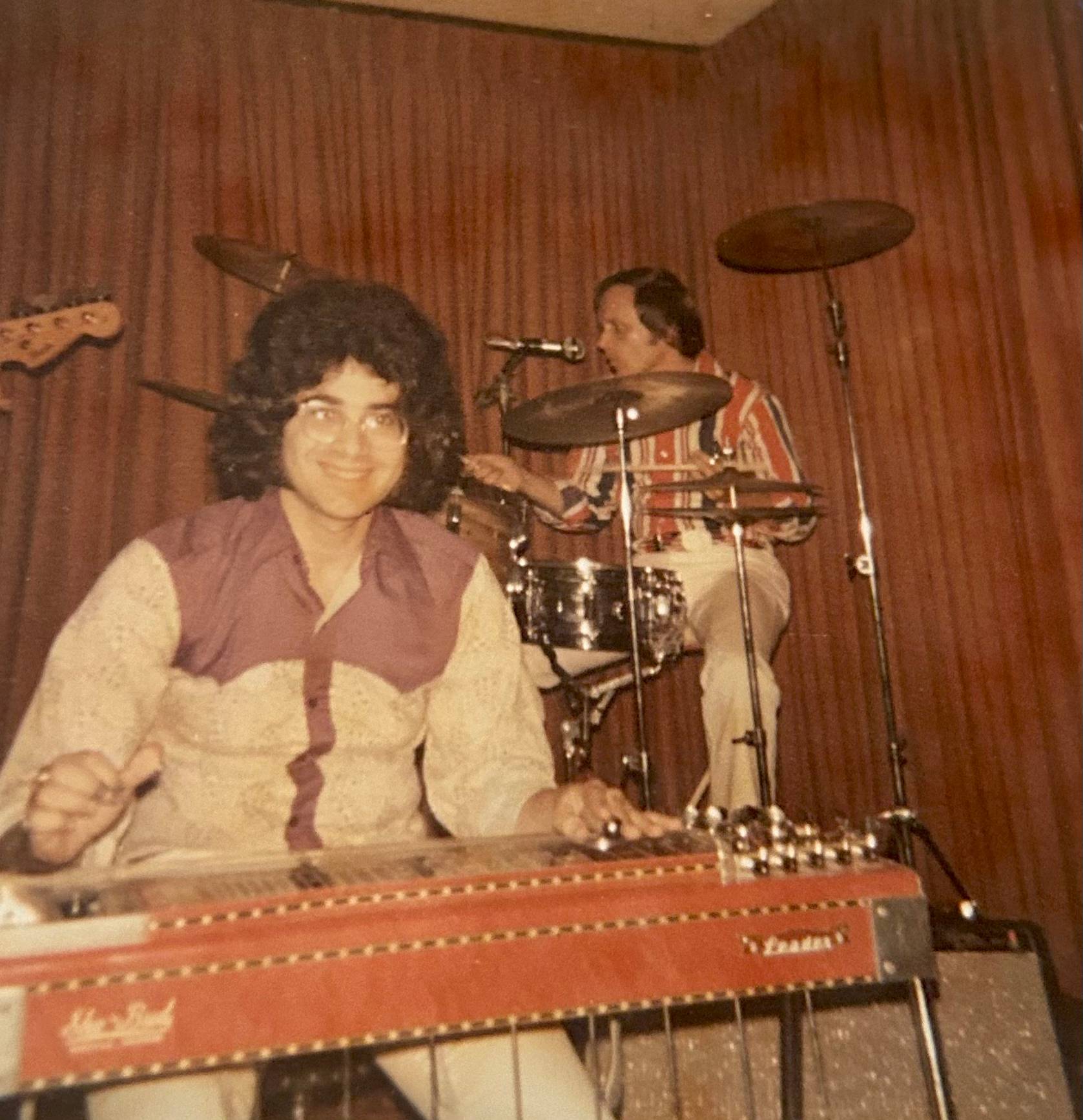

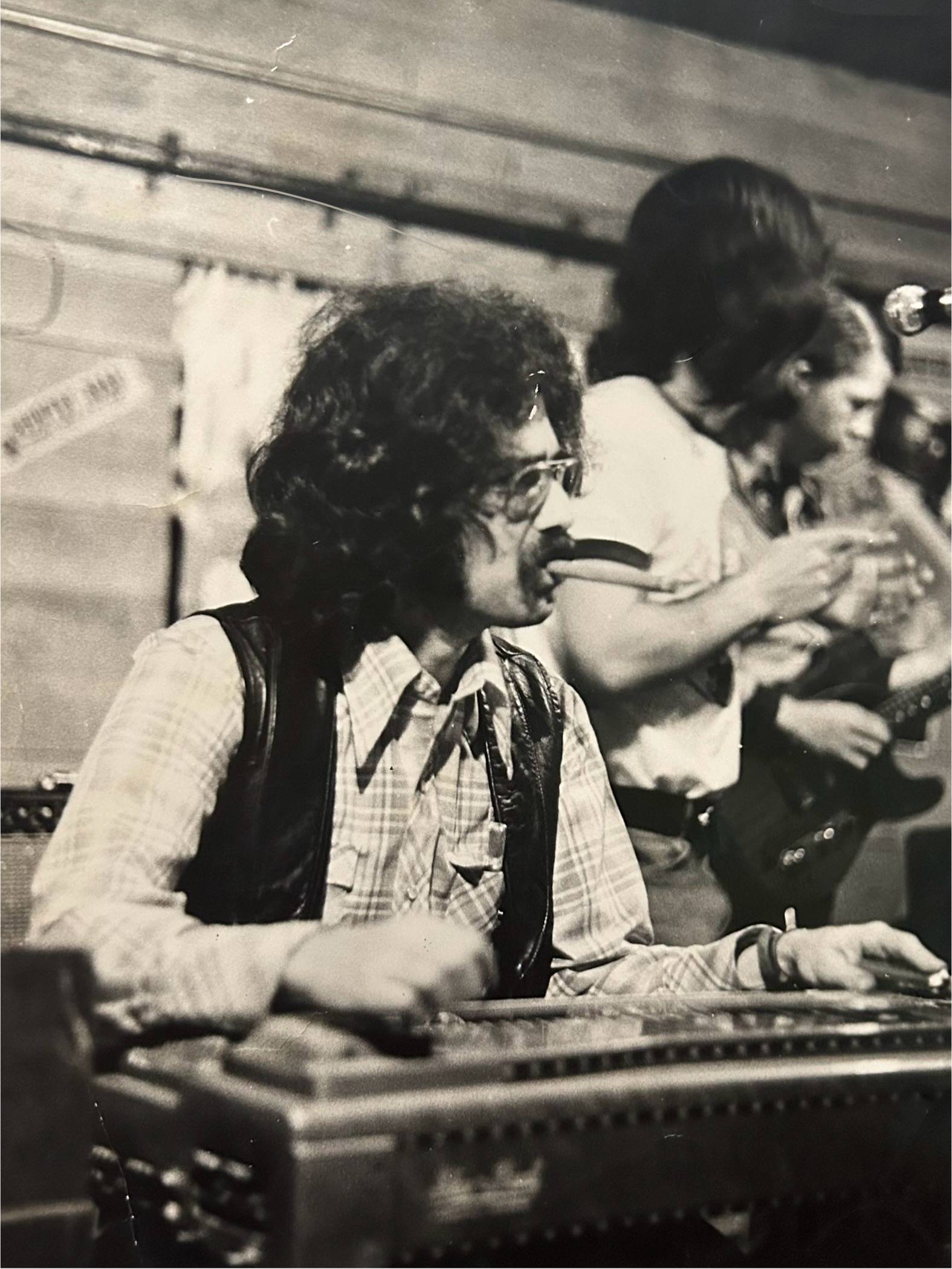

Herb Steiner:

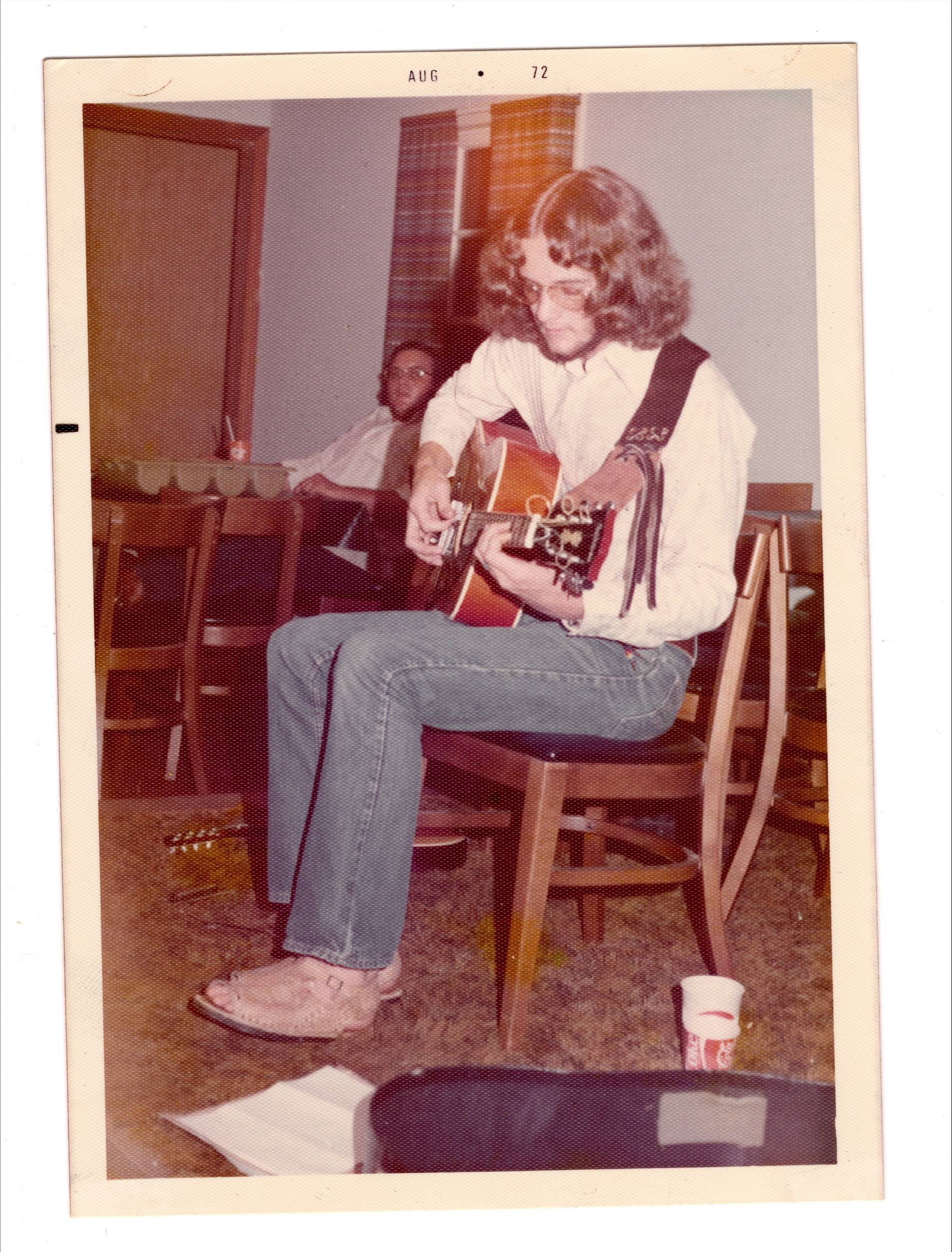

Herb Steiner was born in 1947 in the West Hollywood neighborhood of Los Angeles, California as the son of an elementary school teacher and a local liquor store owner. Steiner describes himself as a “B-level student” in school who “wasn’t really into education…only playing music,” explaining that “school was an afterthought.”39 He began playing music when he was thirteen years old after a neighborhood baseball game where one of his friends arrived with a banjo and a Kingston Trio album. Steiner was so enthralled that he decided to buy a guitar and learn to play. He began frequenting a folk music club in his neighborhood called the Ash Grove, which grew to be an influential venue for the intermingling of old blues players and young artists producing sounds of the folk revival. In his teenage years, he saw artists at the Ash Grove such as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Flatt and Scruggs, and Bill Monroe. In addition to learning guitar, he also taught himself how to play mandolin and started a bluegrass band with his circle of friends.

Steiner attended college at San Fernando Valley State College (now California State University at Northridge) and had a brief stint at U.C. Berkeley, but ultimately droppedout to be a full-time musician. When he was nineteen years old, he went to see a band called the Texas Twosome at Los Angeles’s Troubadour Club.40 Steiner was captivated by the duo – singer-songwriters Michael Murphey and Boomer Castleman – who wore black pants, white collared shirts, and brocade vests while they played country music on matching Martin guitars.41 As fate would have it, a friend of Steiner’s knew Murphey and introduced the two of them. When they immediately hit it off, Steiner invited Murphey and Castleman to what he describes as a “music party” that he was throwing with his friends. Their relationship continued to blossom when Murphey invited Steiner to play on publishing demos he created while working as a staff songwriter for Screen Gems, a publishing branch of Columbia Pictures.42

While Steiner played mandolin on some of Murphey’s publishing demos, he met friend and fellow songwriter Michael Nesmith (who later played with The Monkees). A few years earlier, Nesmith had written a song called “Different Drum,” which was recorded by Linda Ronstadt and the Stone Poneys (a vocal trio with Linda, Ken Edwards and Bobby Kimmel) in 1967. Before the song was released, however, the band broke up. With “Different Drum” quickly climbing the charts and an unfinished Stone Poney album still on the table, she was in need of a new band. After a recommendation from her former bandmate Ken Edwards (who Steiner played with in his high school bluegrass band), Ronstadt called Steiner and asked him to pick up a new instrument – pedal steel – and go on tour with her, to which he agreed. Shep Cooke, another band member from the time, explains that the band “rehearsed like crazy, finished the third Stone Poney album, toured the entire country for two and a half months, [and] played on Joey Bishop’s and Johnny Carson’s TV shows.'”43 By the time this iteration of the Stone Poneys disbanded in 1968, Steiner officially claimed himself to exclusively be a steel guitar player.44

The Los Angeles music scene was much like that of Austin at the time – members of groups such as The Eagles, The Flying Burrito Brothers, The Byrds, and others met up every Monday night at the Troubadour to pick, play, and swap songs. In the mid- to late sixties, these bands among others – such as Crosby, Stills & Nash; The Mamas and the Papas; and Buffalo Springfield – pioneered a folk-rock scene in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Laurel Canyon. Concurrently, The Eagles were forming in Hollywood, defining a new era of the Southern California sound. Steiner explains that at this time, there was somewhat of an “interchangeable” nature to the group of musicians playing in Los Angeles. Like Austin, there were always musicians looking for bands, bands looking for musicians, managers looking for bands, and bands looking for managers.45

In 1970, Steiner linked back up with Michael Murphey and Boomer Castleman in Los Angeles to form a country band called Tex. The group played the plethora of honky-tonks and country bars in Los Angeles and all over Southern California. This was short lived, though, as Murphey became disillusioned with Southern California and moved back to Austin in January of 1971 with a newfound friend and co-conspirator, Bob Livingston. Meanwhile, Herb stayed and continued playing at the honky-tonks in Los Angeles.

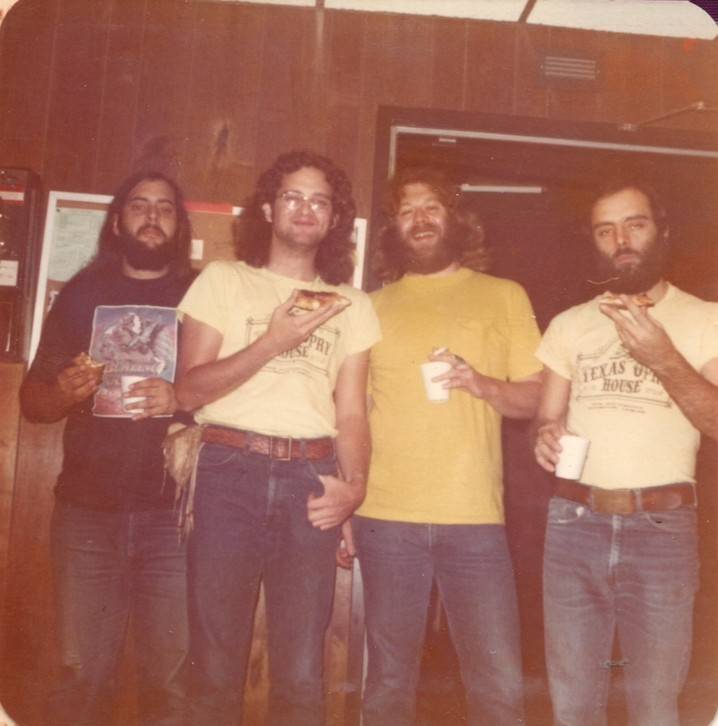

In early 1972, Murphey returned to Los Angeles with his new band from Austin – which Steiner interchangeably calls the “Michael Murphey Band” and “The Texas Band.”46 The group had a two-night gig at the Whiskey a Go Go, opening for the British rock band the Strawbs. Murphey asked Steiner to play with them that night, and he agreed. In an interview with Steiner, he recalls that when they pulled into the parking lot of the club, they were met by a rude parking lot attendant who would not let them park their van to load in their equipment backstage. In response, Craig Hillis apparently sneered at the attendant and exclaimed, “Boy! We’re from Texas, and we’re not on no peace loveee trip!” This seemingly did the job, because they were able to park the van and load in after that.47 After the show at the Whiskey a Go Go, Murphey’s manager insisted that Steiner move to Austin to help the band rehearse for a European tour. He obliged, and played with Murphey at clubs all over the city as the “top band in town.”48

Michael McGeary:

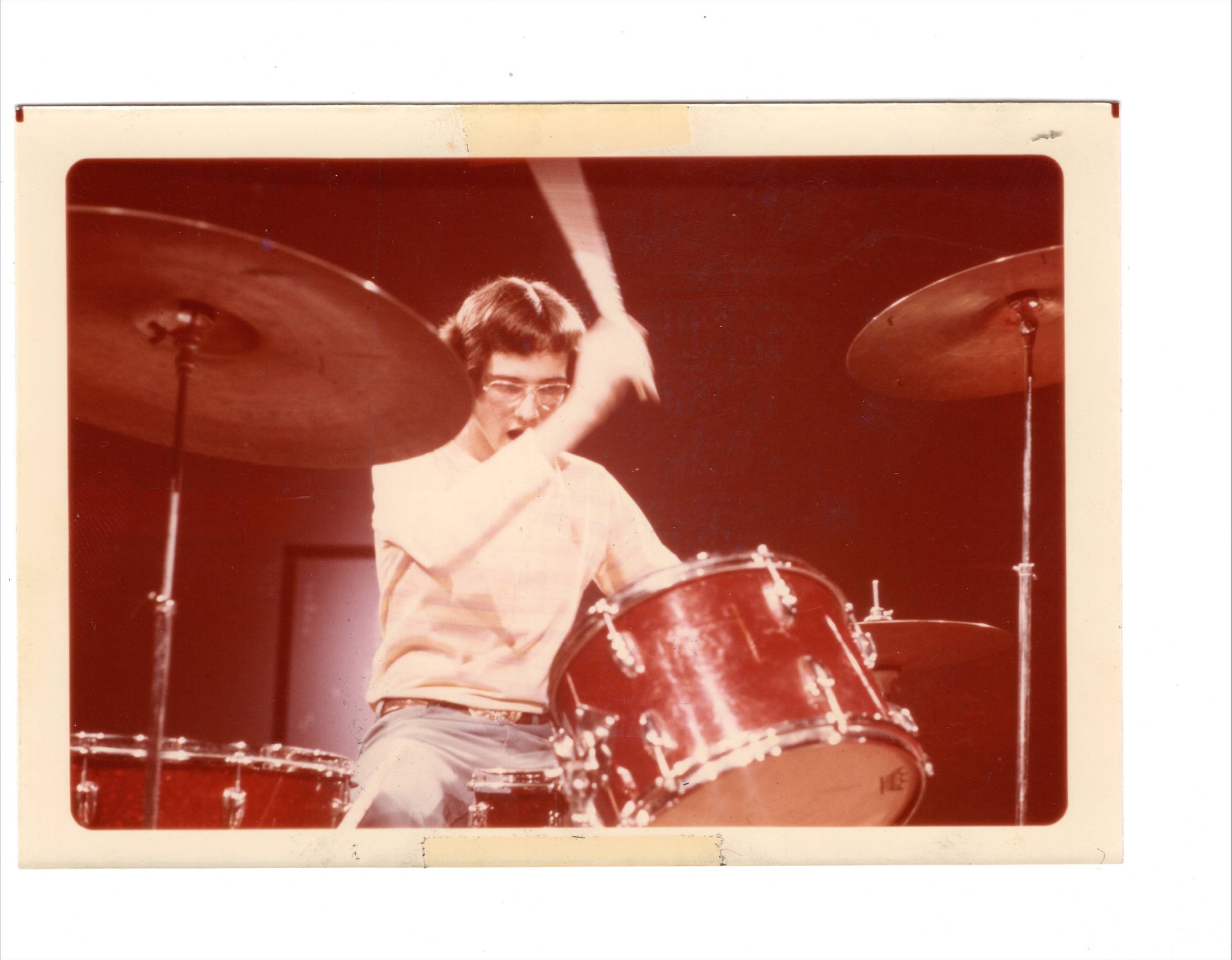

Michael McGeary was born in Escanaba, Michigan in 1945 and moved to San Diego when he was five years old, where he spent most of his childhood. When his school and home life were difficult, McGeary turned to music – he began taking drum lessons when he was nine years old and played in the school band while engaging with rock ‘n’ roll drumming on the side. He eventually dropped out of school and joined the military, attending jet mechanic school in Amarillo.49 Narrowly missing the Vietnam draft, McGeary joined the United States Air Force on his own accord in 1963 and was stationed at Ent Air Force Base in Colorado Springs.

McGeary worked with NORAD (North American Air Defense Command) – a military organization that is charged with the aerospace defense of Canada and the United States. He served on the ground crew, helping receive and dispatch planes to and from NATO countries who were visiting NORAD. McGeary started playing drums in a soul band composed of a few of his fellow ground crew members before he was drafted into the distinguished NORAD Band, composed of musicians from the United States Army, Air Force, and Navy, along with members of the Canadian Armed Forces.50 The NORAD Band traveled all over the North American continent and made high-profile appearances at events such as the Canadian National Exhibition, New York’s World Fair, and annual performances at Carnegie Hall. Although McGeary’s career in the Air Force came to a close in 1964 – just a year after he joined – due to a large-scale firing of non-essential personnel, the skills and discipline he learned while playing in the NORAD Band would prove important in his future career as a musician.

In 1967, McGeary moved to Hollywood’s Laurel Canyon neighborhood. He briefly played drums with the Standells, a garage rock band from Los Angeles whose recent release, “Dirty Water,” was climbing the charts. But McGeary’s real interest lay in the theater, and he began working with an improvisational comedy group in the late sixties. He describes his time with this theater company – led and organized in-part by Del Close, an influential teacher who coached some of the nation’s most well-known comedians and comedic actors – as “the beginning of growing up.” McGeary remembers this time in his life fondly, explaining that members of the company were a “unique slice of humanity” who were “educated, sophisticated, and in the thick of the social and political storm.”51 He explains that Close encouraged an “untamed” approach to theater, allowing for actors to have creative freedom to express themselves – a theme that would also resonate with Austin musicians in the early 1970s.

As fate would have it, one night at a cast party for the improv group, McGeary met two Texas musicians – Ray Hubbard and Bob Livingston – who happened to be friends of one of the actors in the company. Their band, Three Faces West, was in town to play at Pasadena Ice House, a folk club in a town of the same name about 11 miles outside of Los Angeles. The duo invited McGeary to play drums with them that night. A few weeks later, McGeary received a letter from Murphey asking him to come play at the Chequered Flag in Austin. He continued to play with Murphey and his band during an era that he describes as one of the “happiest times in his life,” remarking that the band accepted him fully for who he was, “odd California hipp[ie] ways and all…”52

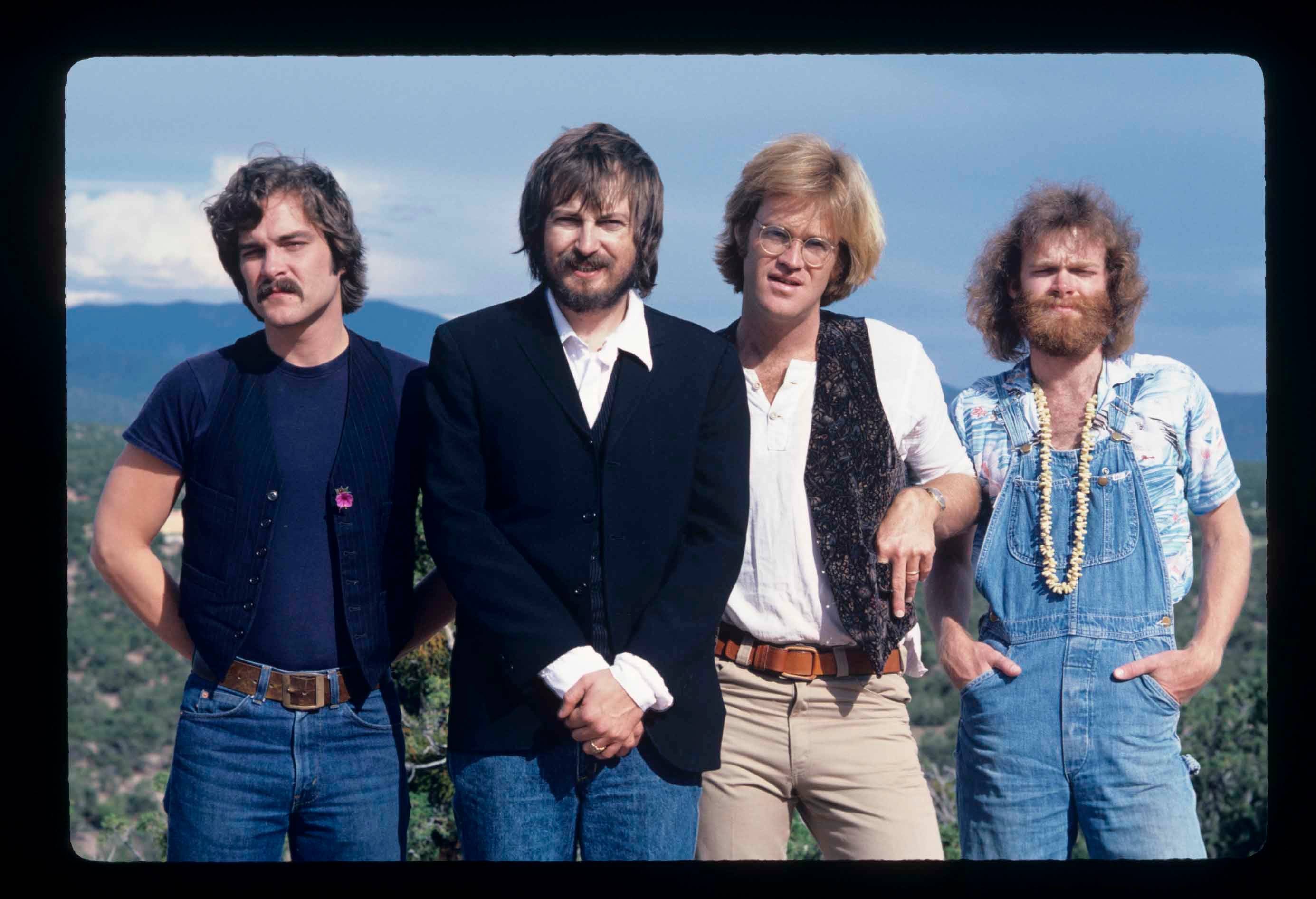

The personal backgrounds and early career experiences of the Lost Gonzo Band contributed heavily to their reputation as an “interchangeable” group of talented musicians when their lives converged in Austin. Coming from far across Texas, the U.S., and the world – from Los Angeles, to Denver, to New Mexico, to Nashville, to England – their individual stories are emblematic of the varying facets of the band’s influence in the rise of a new era of music. Rural childhoods, military upbringings, exposure to different cultures, generational oral tradition, the Vietnam War draft, and the social and political climate of the United States were all facets of the Gonzos’ lives that retroactively aided in building the band into one of the most versatile, resourceful musical groups in Austin.

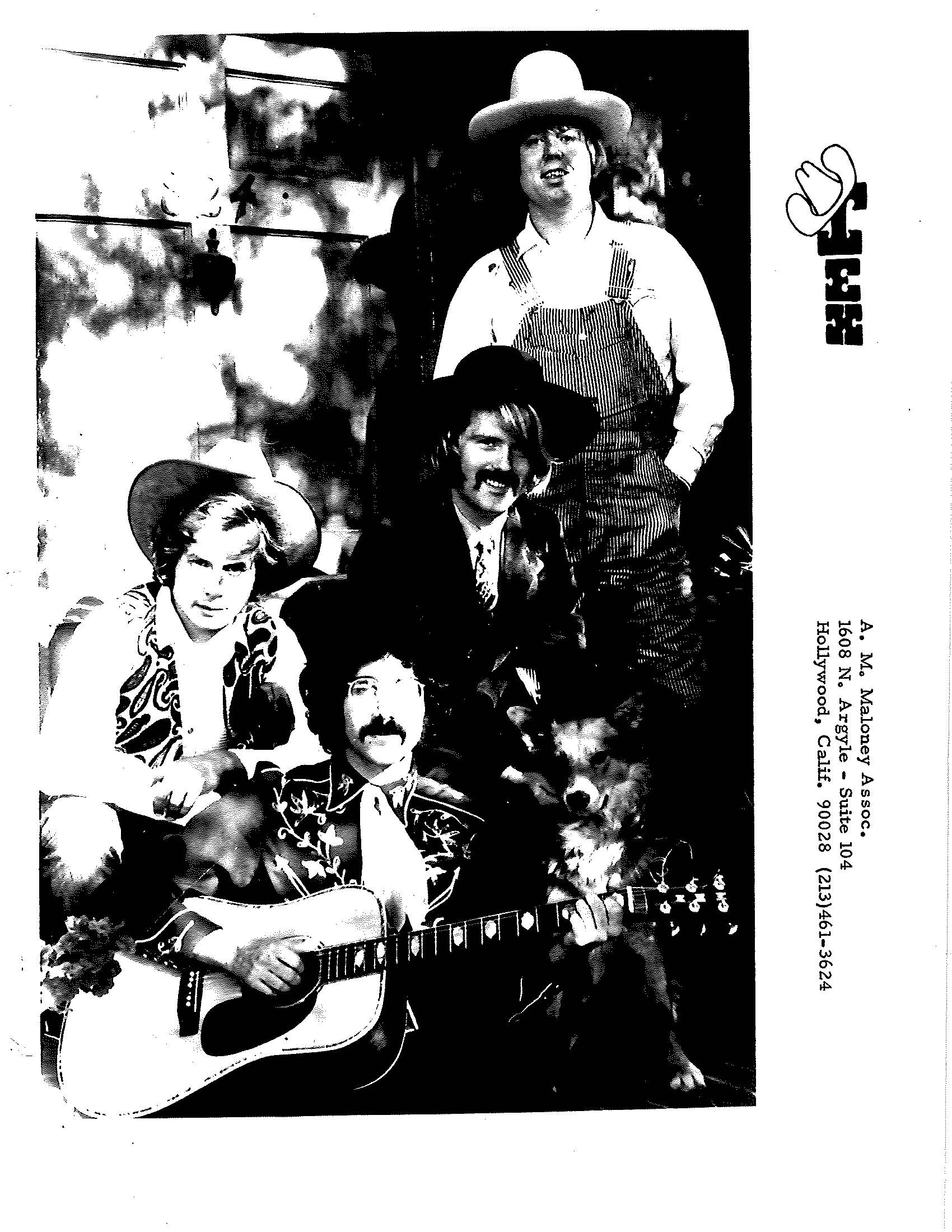

Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir, ¡Viva Terlingua!, and the Genesis of Gonzo

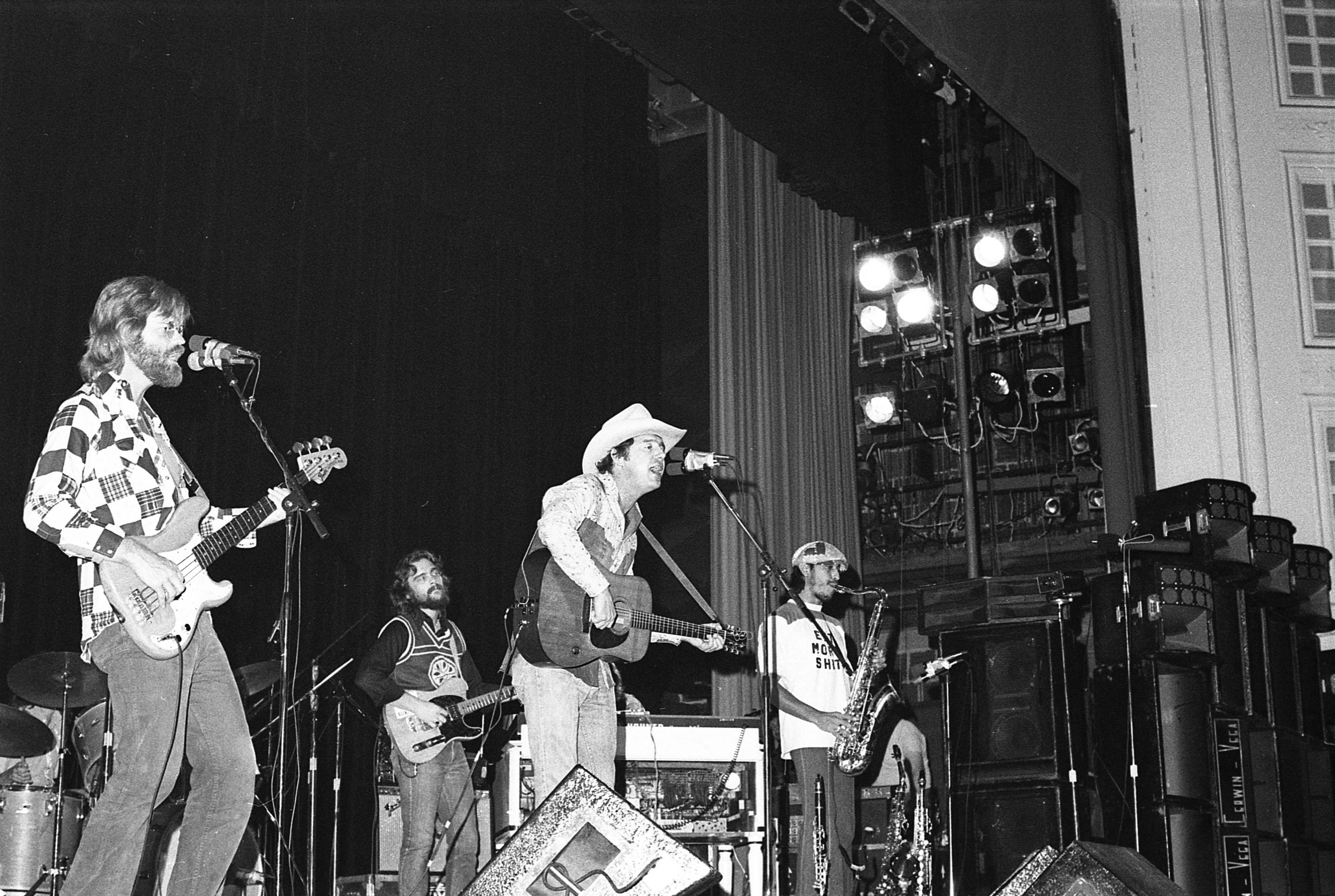

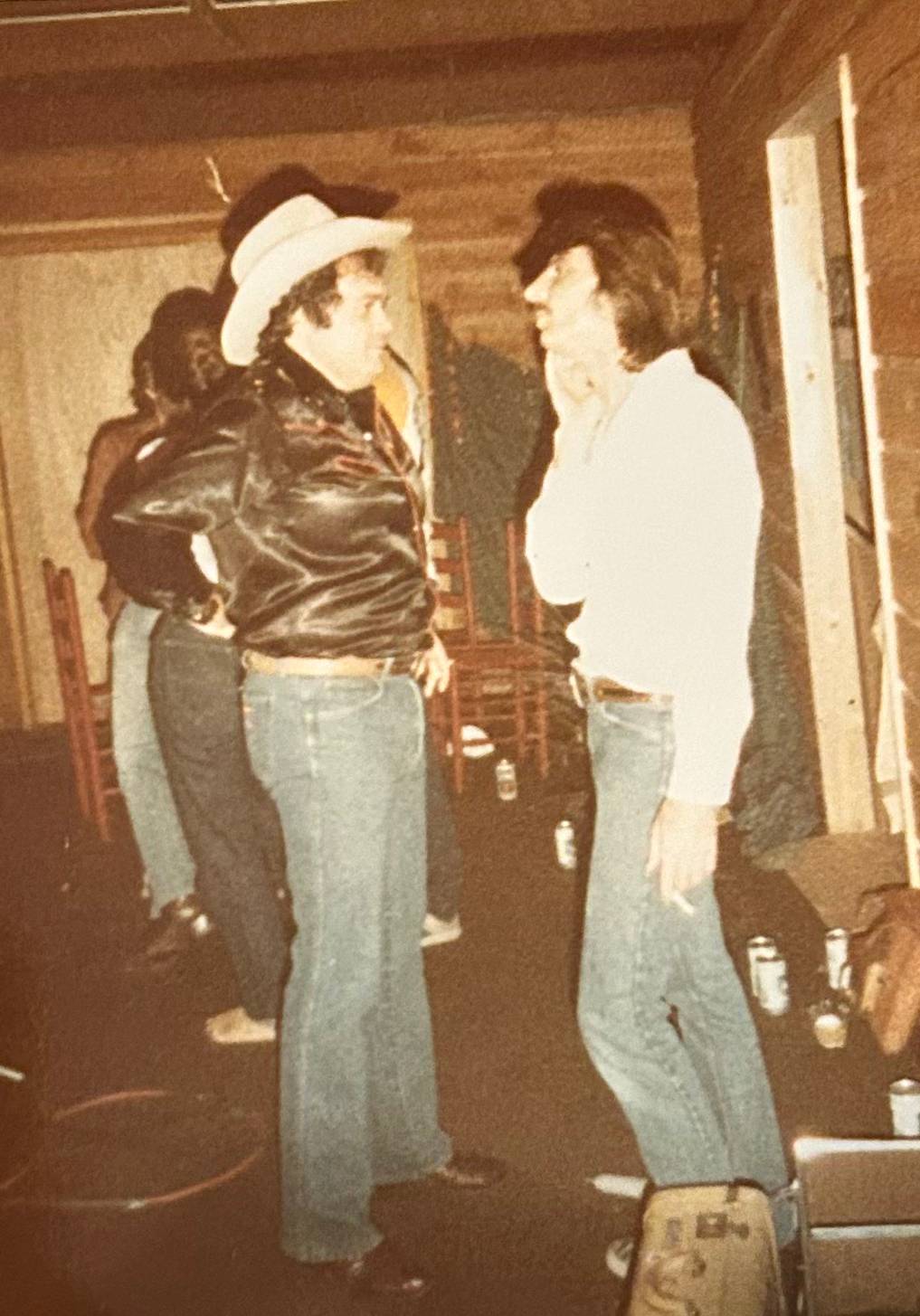

Michael Murphey released the album Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir in 1973, whose title track, “Cosmic Cowboy Pt. 1,” captured an evolving spirit of country music. The song, about an urban hippie who hopes to escape to Texas and take up a rural lifestyle, draws on themes of an ongoing “cosmic” drug culture and the image of a conservative Texas “cowboy,” which had recently resurged in popularity. The song grew to define the burgeoning progressive country music scene in Austin, and remained in public consciousness even when it dropped off the charts.53 Hippies and rednecks began to frequent the same Austin beer joints with the newly opened Armadillo World Headquarters as their shared watering hole. Murphey’s newly assembled band – consisting of Bob Livingston, Gary P. Nunn, Craig Hillis, Herb Steiner, and Michael McGeary – had varying personal backgrounds and musical experience, and proved to be incredibly adept at morphing their styles to accompany any artist. This group of musicians casually became known as the Austin Interchangeable Band.54

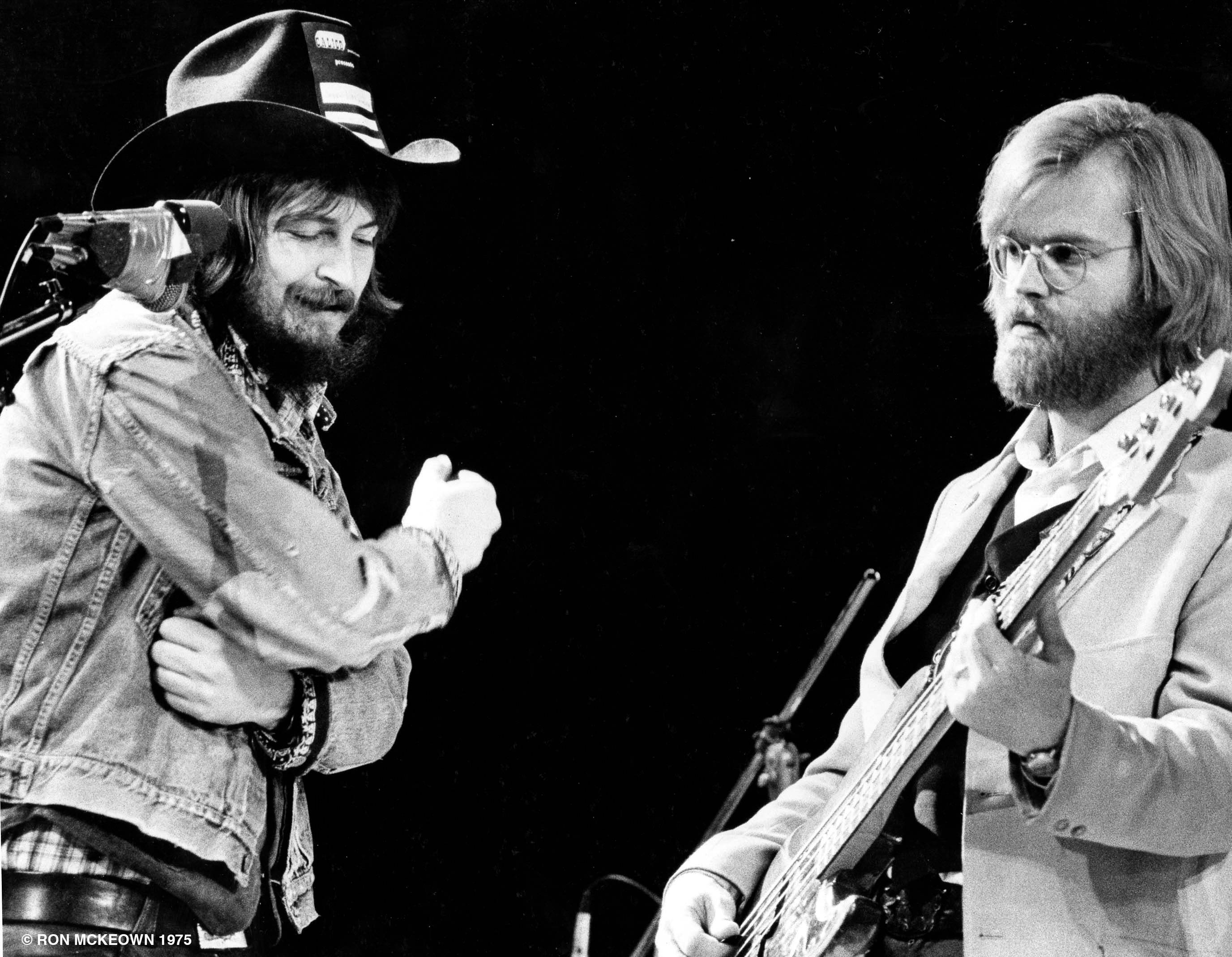

Jerry Jeff Walker – a folkie originally from Oneonta, New York – moved to Austin, Texas, in 1971 after years living as a traveling troubadour on the road. Walker’s career took shape in New Orleans as a street performer, and his recently released “Mr. Bojangles” was already well-known across the country. He arrived in Austin with a contract with MCA Records, which included a promise to produce a new album. In order to fulfill this promise, he needed a band. However, Walker didn’t want just any band – he wanted to work with a group of musicians who would fit in with his beliefs and philosophies about music and performing and who listened to “jazz and blues, some rock and roll, some country... guys with the background to follow [him] wherever [his] impulses led.”55

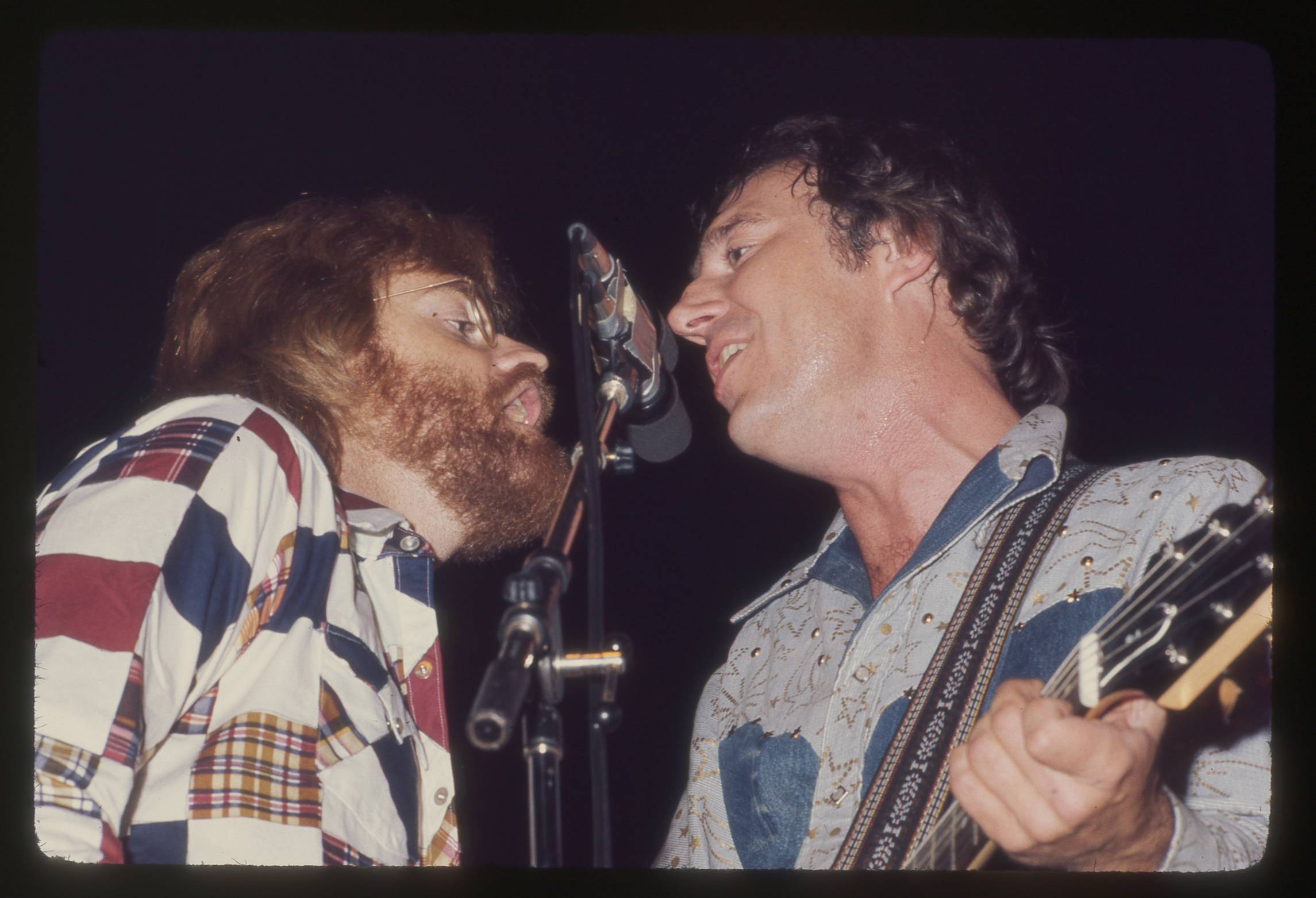

While Austin was full of good musicians, the Austin Interchangeable Band had a growing reputation for being the best in town. Gary P. Nunn could navigate “just about every instrument [in] a country-western band;”56 Craig Hillis played with skilled, poetic singer-songwriters such as Steven Fromholz and Dan McCrimmon; Bob Livingston was a professional character who had ample experience in the folk scene across the South; Herb Steiner brought a distinct country sound into the mix with a steel guitar (Livingston claims Steiner “invented progressive country music on the spot”57); and Michael McGeary held it all together with a steady beat. One fateful night, Walker arrived at an old motor court on Lamar Boulevard in Austin where Murphey was practicing with the band. After joining in on a lengthy jam session with the band where Walker fit right in, Murphey agreed to loan him the band so he could cut his promised record for MCA.

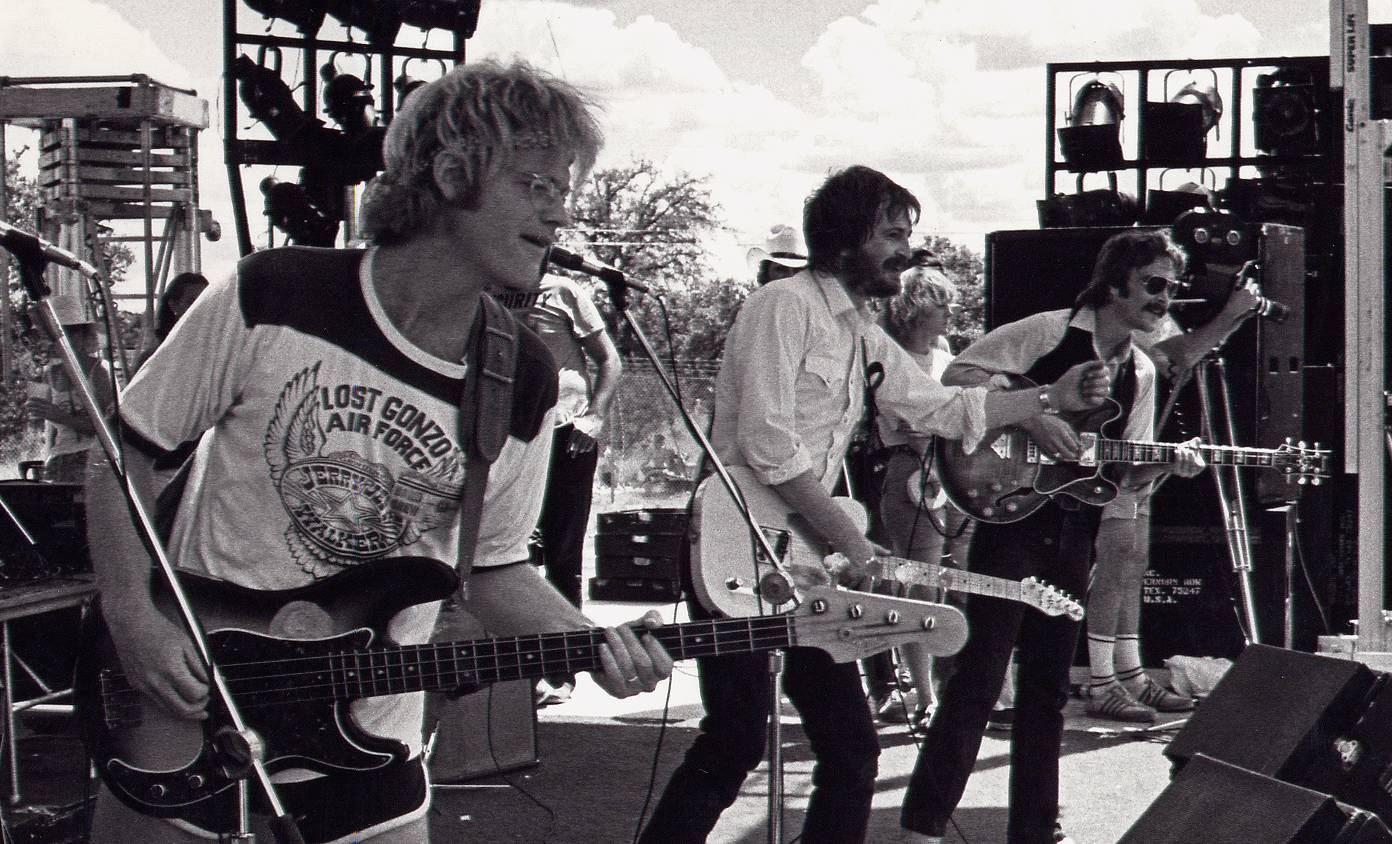

Walker and the skilled players joined forces to create one of the most formative recordings in Austin music history.58 Instead of assembling at a typical recording studio, Walker scheduled this session to be held at an old, abandoned dry cleaning establishment, previously known as Rapp’s Cleaners, on 6th Street in Austin. Walker despised recording studios and actively avoided them, calling them “sterile” and comparing them to hospitals with all of their gadgets and wires.59 Like most of his rehearsals, he scheduled this one to begin at 10:00 P.M., and had already mixed up a five-gallon water cooler of sangria wine by the time the band arrived. According to Gary Nunn, the band’s primitive recording environment created an aura of authenticity and spirit of creative improvisation. He recalls that they were essentially “learning the material as [they] went, recording every pass live.”60

After this recording, the band split their time between working with Murphey and Walker, playing songs from both Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir and Jerry Jeff Walker to audiences all over the country. Walker – who was known for his laidback, free-wheeling approach to recording and performing – increasingly appealed to the band. This approach directly grated against that of Murphey, who prioritized professionalism, discipline, and perfection. Livingston compares Murphey to the “Vincent Van Gogh of country rock...he’s a genius, and he wrote these incredible songs, but it just felt like he was going to cut his ear off at any moment.”61 For the time being, the band stopped working with Murphey and joined Walker on his next project – this time, in a tiny Texas Hill Country hamlet called Luckenbach, Texas.

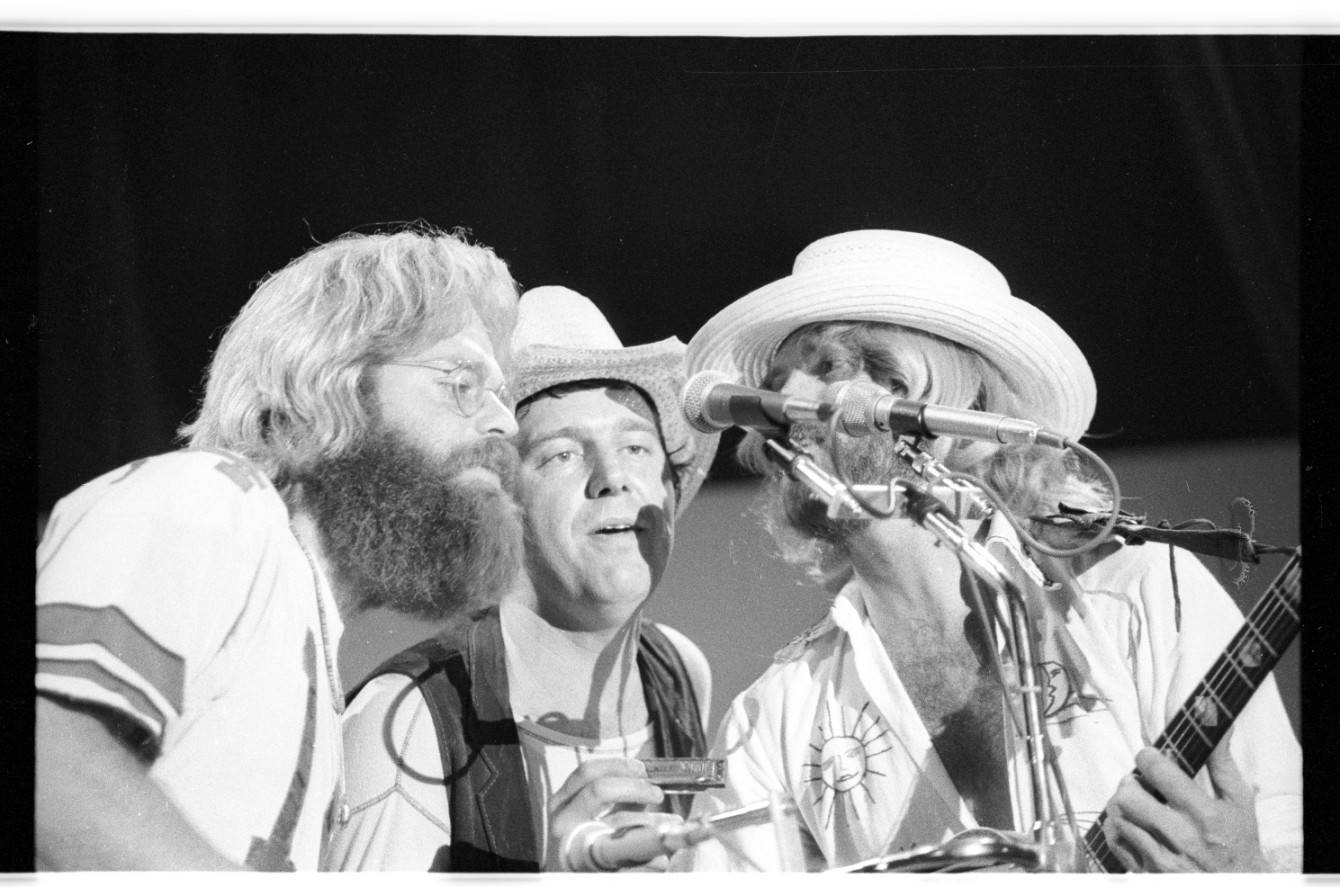

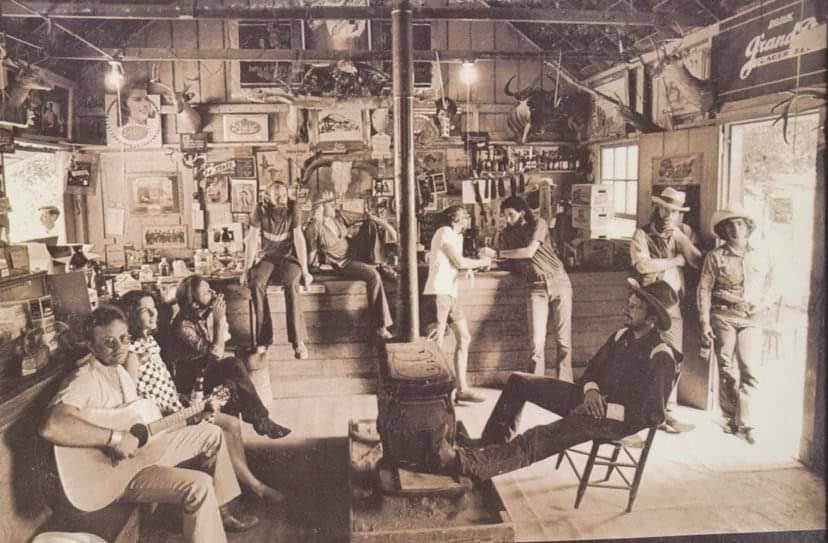

The town of Luckenbach was purchased a few years earlier by Hondo Crouch and Guich Koock and consisted of only five permanent structures, including a post office and a dance hall. In August 1973, Walker and the band set up in the town’s dance hall, using bales of hay as sound baffles and running microphones to the mobile recording studio, “Dale Ashby and Father Sound Recorders,” parked out under the oak trees. The band brought along Mary Egan, a remarkable fiddle player from the Armadillo World Headquarters’ house band, Greezy Wheels, who adds female voice and talent into the recordings.62 They also brought harmonica player Mickey Raphael, who played extensively with Willie Nelson over the years and remains in his band today. Walker had virtually nothing written when they arrived in Luckenbach – just some “ditties” and a few covers that he liked from other artists. The rest of the week was spent sitting around in a circle in the middle of the dance hall, taking part in something that mimicked a sophisticated jam session, which would yield one of the most renowned works in Austin’s music history: ¡Viva Terlingua!

During the recording sessions, Craig Hillis remarks that songs were produced somewhat spontaneously, recalling that “everybody just put something in the Gonzo soup and stirred it up”63 – which is exhibited on tunes such as “Gettin’ By” and “Sangria Wine.” On songs such as Guy Clark’s “Desperados Waiting for a Train” and Michael Murphey’s “Backslider’s Wine,” the band seamlessly matched pitch and constructed harmonies with Walker, adding to the breadth of the sound on the album.64 Later in the week, a concert was held at Luckenbach dance hall, where songs such as Gary Nunn’s “London Homesick Blues” and Ray Wylie Hubbard’s “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother” were recorded by the band with a live audience in the background. Both Nunn’s and Hubbard’s songs would evolve into progressive country anthems that became synonymous with the Austin music scene and the cosmic cowboy movement – due, in large part, to the way they were executed on ¡Viva Terlingua!. The live audience essentially became an additional instrument in the recordings, proving arguably just as important as the music itself. The shared experience of live music – emphasized by Walker and the Austin Interchangeable Band on ¡Viva Terlingua! – would grow to be a defining feature of the Austin music scene and the progressive country movement.

While stereo purists and radio executives snarked that ¡Viva Terlingua! was “poorly recorded,” the album certainly established Walker’s popularity as the patron saint of progressive country music in Texas. Upon its release, ¡Viva Terlingua! swiftly sold 50,000 copies in Texas and only 20,000 more in the rest of the country, solidifying its status as a cult classic in the Lone Star State.66 Walker’s band decided to officially christen themselves with a new name as they embarked on a new leg of their journey together. They collectively decided on the “Lost Gonzo Band” in honor of Hunter S. Thompson, the patron of the “Gonzo journalism” movement – often associated with the sixties counterculture and anticommercialism.67 Musicians in Austin frequented the same hangouts as Gonzo journalists, as both groups rejected corporate controls and preferred existing in an environment where they could nurture artistic visions.68 In his book, Walker explains “Gonzo-ism” as “taking an unknown thing to an unknown place for an unknown purpose,” claiming “that’s what [the band] was doing, but we were also lost.”69

Following the genesis of the Lost Gonzo Band, the group’s members began to change as well. Craig Hillis and Herb Steiner left the band after the production of ¡Viva Terlingua! to play with Michael Murphey as he produced his self-titled album in 1973. Michael McGeary left the band the same year due to differences between him and Walker. Nunn notes that McGeary and Walker both had the same type of “in-your face” personality, recalling that they didn’t always work well together.70 The Gonzos welcomed guitarist John Inmon and drummer Donny Dolan to the group for their next set of albums. Tomás Ramirez, a renowned saxophone player, also became a mainstay in the Lost Gonzo Band during this time, adding another distinct layer to the band’s eclectic country crossover sound.

Through their association with both Murphey and Walker, the Lost Gonzo Band created a distinct musical philosophy and pioneered foundational ideologies that became central to Austin’s music scene. Their critical involvement in the creation of albums which laid the groundwork for the progressive country movement would ultimately secure the band’s status as movers and shakers in cultivating Austin’s reputation as a center of musical performance.

The Next Gonzo Generation

As the Lost Gonzo Band evolved over the following years, various musicians joined and left – some only playing on one or two albums. However, two individuals have remained consistently in the Gonzo orbit. John Inmon and Freddie “Steady” Krc were not members of the first incarnation of the Lost Gonzo Band, but are critical to the telling of the history and lasting significance of the group.

John Inmon:

Born in San Antonio in 1949, John Inmon grew up as an “army brat” and lived in various cities across the United States such as San Francisco, Denver, and Washington D.C. His family moved to Heidelburg, Germany, in 1960, which was the European headquarters for the United States Army, where his father was stationed as USAREUR’s Chief of Medicine during the Cold War. Living in Europe during the Cold War made for a unique childhood experience. Three months after the Inmon family moved to Germany, the Berlin Wall was erected; Inmon notes that, at any given point, it felt as if they were “just minutes from being vaporized.”72

In Germany, Inmon says that there was not an abundance of kid-friendly activities to partake in after World War II, as the country was still rebuilding and lacked substantial television or radio networks. People often listened to a radio station out of Luxembourg, called Radio Luxembourg, which played rock ‘n’ roll music.73 Inmon generally appreciated music and regularly listened to Radio Luxembourg, but it wasn’t until his sister’s boyfriend taught him how to play guitar that he knew he wanted to be a musician himself, explaining that that is when he realized that he “just had to have it…it had to be rock ‘n’ roll…that was it.”74

The guitar soon became Inmon’s obsession. His family moved to San Francisco when he was a teenager where he formed a surf band with a few friends. He became completely immersed in music, playing both drums and guitar. When Inmon’s family moved to Temple, Texas, when he was sixteen, it quickly became apparent that the nearby town of Austin was the center of the state’s music scene. Inmon was a member of bands called The Reasons Why and The Chevelles who played at clubs all across Austin, along with frat parties at the University of Texas.75 The Chevelles also played at clubs and frat parties around Austin (as Livingston mentioned, frat parties were a great paying gig for small bands), singing tunes by The Beatles and other “Top-10” hits.76

When he graduated high school, Inmon enrolled in a junior college in Temple before attending the University of Texas. The Vietnam War was raging and affecting young people in large numbers, ultimately breaking The Chevelles apart. Inmon, who was looking for another band, was approached one night by Gary P. Nunn at the New Orleans Club and was asked to join Nunn’s band, Genessee. The band lived in a big house that overlooked Austin on the west side of town; its big open rooms and lack of neighbors made it perfect for jamming, attracting frequent visitors such as Rusty Weir, B.W. Stevenson, and Jerry Jeff Walker.77 As aforementioned, the band adopted a folk sound and started focusing on writing original songs, so Inmon gained significant experience in folk songwriting after playing rock ‘n’ roll music for his entire career. In the spirit of being fully committed to playing music, Inmon made the decision to drop out of the University of Texas and play full-time with Genessee and other bands around Austin in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Inmon joined the Lost Gonzo Band when Craig Hillis left in late 1973 after the recording of ¡Viva Terlingua!. He admits that he doesn’t know how to read music, noting in an interview with the Austin American Statesman that he just “hear[s] notes in [his] head and play[s] them.”78 This, along with Inmon’s background in rock ‘n’ roll and natural talent to improvise and adapt, furthered the narrative of the collaborative, flexible, eclectic talent of the Lost Gonzo Band and their contribution to the Austin music scene in the 1970s.

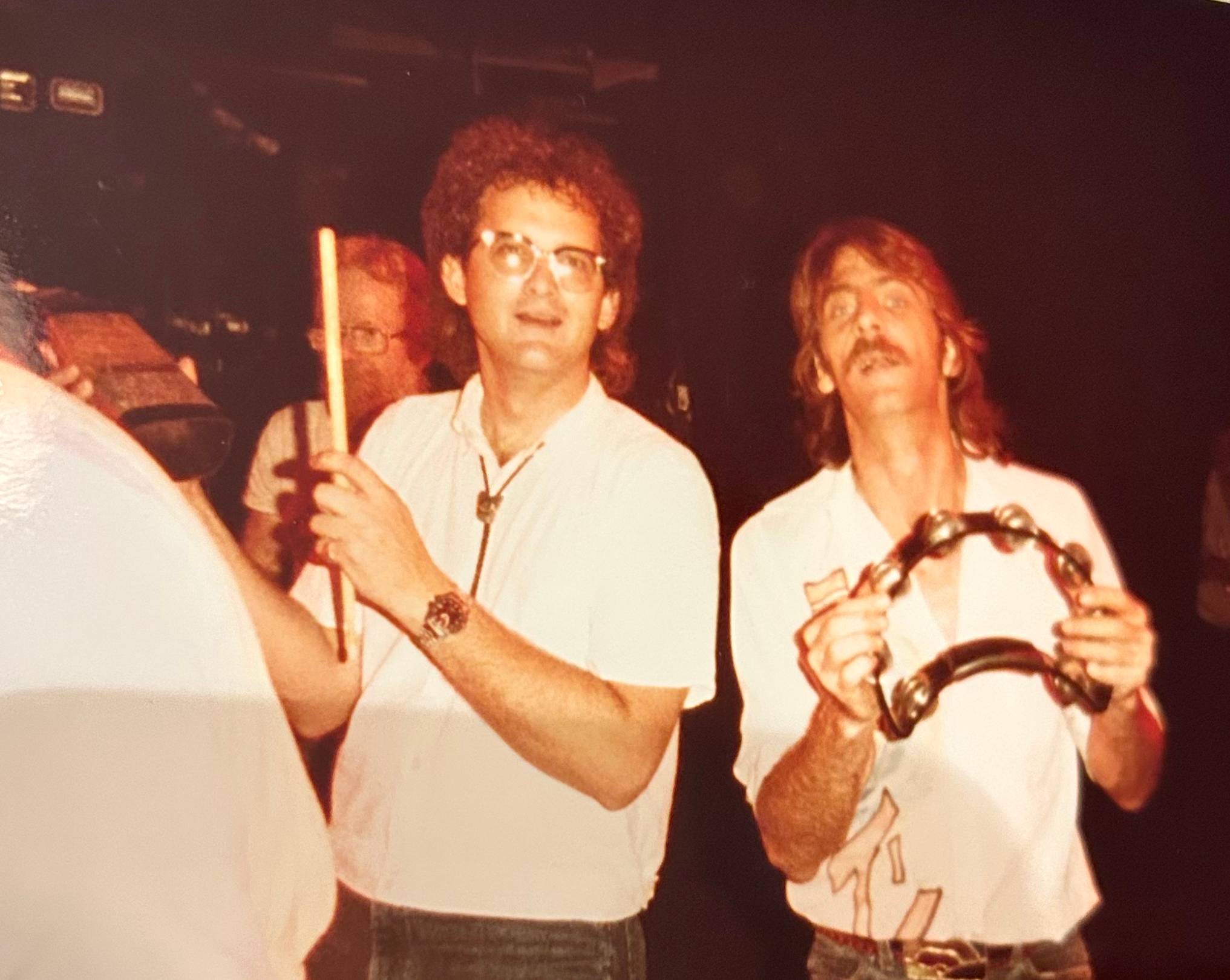

Freddie “Steady” Krc:

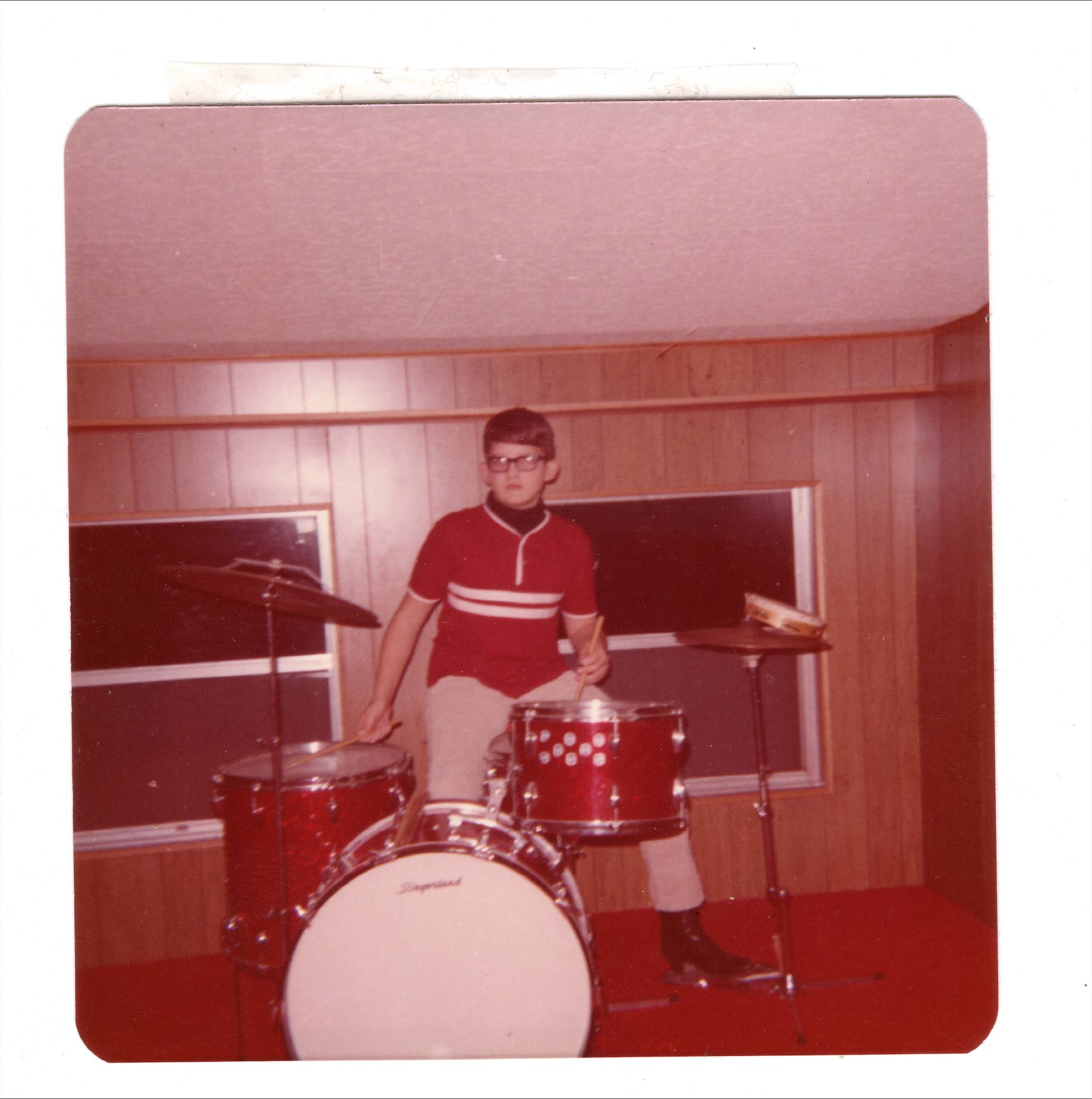

Freddie Krc grew up in La Porte, a small town between Houston and Galveston on the Gulf of Mexico. His father worked for Shell Oil Company, and his mother was a substitute teacher and worked at the library at the local high school. Krc came from a musical family; his paternal grandmother and her family played in the Czech Krenek family orchestra since 1864, arguably making them the oldest family band in the United States. Because of this, Krc was exposed to and began playing music at a young age, describing himself as a true “Beatle Kid” who became obsessed with music after seeing The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. At nine years old, he began taking drum lessons and started a rock band called The Sound Kings that played at the community center in La Porte.79

Krc notes that his family home was situated out in the countryside, which allowed him to practice drums at all hours of the day without bothering the neighbors. He was a well rounded musician by his teenage years; he was invited to play with the junior college jazz band while he was still in high school, and even performed splash-down parties for the astronauts on the Apollo 12 and Apollo 13 missions at Johnson Space Center. When Krc graduated high school a half-year early, he enrolled in Lon Morris Junior College in Jacksonville, Texas, where he majored in Theology and minored in English – both subjects he thoroughly enjoyed. However, Krc explains that he “just couldn’t quit playing music.”80

Krc dropped out of college to pursue what he was truly passionate about. He moved to Dallas before migrating south to Houston and playing in a hotel lounge band, claiming that he was “having so much fun getting to play for four to six hours a night” that he didn’t consider “how uncool it was.”81 The trajectory of Krc’s life changed forever when he went to see Michael Murphey play at Liberty Hall in Houston one night. He ventured backstage at the venue and met Herb Steiner, who was playing steel guitar with Murphey at the time. When Krc questioned Steiner – who was about ten years older than he was – about how to “get serious” about playing music, Steiner exclaimed, “Well, move to where the music is!”82 With a new sense of excitement, Krc settled in Austin in 1974.

In Austin, the music scene was thriving after the success of Walker’s ¡Viva Terlingua!, Murphey’s Geronimo’s Cadillac and Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir, and Willie Nelson’s Shotgun Willie. Upon arrival in the state’s capital, Krc started playing with a Dixieland band who had a gig five days a week at a local barbecue restaurant. For every gig, he recalls that he made “five dollars, a plate of barbecue, and all the tips [he] was too painfully shy to ask for.”83 In June 1975, Krc was hired to play drums with B.W. Stevenson – a Dallas native who lived there throughout most of his musical career, although Austin claimed him as their own. At twenty-four years old, Stevenson rose to national stardom after his big hit, “My Maria,” topped the charts in 1973.

At the age of twenty-one, Krc traveled to Los Angeles to make a record with Stevenson called We Be Sailin’ – an opportunity that afforded Krc the credibility to launch his career as a professional musician. Stevenson refused to use studio musicians for the album and made the risky demand that he would only record if he could use his own band. This brought significant recognition to Krc (who had never been on a major record label) and the rest of the band, highlighting the trust Stevenson put in them. Krc played with Stevenson for a little over a year and a half, claiming it to be one of the most rewarding experiences of his career.

In early 1977 at the young age of twenty-three, Freddie Krc joined Jerry Jeff Walker to play drums on the final tracks of A Man Must Carry On. He joined a group of backing musicians who would come to be known as the “Bandito Band,” who played with Walker on the next three albums he produced. Krc continued to play on and off with Walker into the 2000s. Krc’s cross-genre musical experience allowed him to be an adaptable and resourceful backing musician for Stevenson, Walker, and psychedelic icon Roky Erickson. He also fronted his own band – power pop trio The Explosives – and pioneered several other musical projects such as the Shakin’ Apostles, the Freddie Steady 5, and Freddie Steady’s Wild Country. Krc became influential in the later incarnations of the Lost Gonzo Band and would go on to play an essential role in maintaining the legacy of the progressive country movement and the Austin music scene more broadly.

Conclusion

This project is a result of a long journey in the practice of oral history. The larger version of this effort includes conversations around the roots of the Austin music scene and progressive country scene more broadly, along with an added focus on the Gonzos’ careers in more recent years. In my interviews with band members, I intentionally took a “life history” approach – asking questions about their personal lives outside of their years with Jerry Jeff Walker and Michael Murphey. In examining their larger life stories, it became clear that each narrator had their own distinct experiences and background that contributed to the making of what it meant to be “Gonzo.”

Because the stories of the Lost Gonzo Band have not been previously documented, I wanted the musicians to play a participatory role in writing their own history. By taking part in the storytelling process, the Gonzos were able to aid in constructing their history in their own words. Further, I overlayed these stories with the archival record, which allowed me to scrutinize historical memory and contextualize the greater influence of the Lost Gonzo Band. This journey began in October of 2021, when I was invited to attend a band rehearsal by Gonzo manager D Foster. The band was recently reunited under Foster’s guidance, and had a big reunion show coming up at Gruene Hall at the end of the month.

As I pulled up to the Lost Gonzo Band rehearsal at the Space ATX recording studio in South Austin, my stomach churned. Space ATX had a very modern feel to it. Although it was situated under a blanket of towering oak trees (much like the Luckenbach dance hall), the architecture of the building was made up of straight, clean lines, and the lobby smelled like a dentist office. Everything I knew about the Lost Gonzo Band led me to expect their recording studio of choice to be ragged and informal, but this building was far from Rapp’s Cleaners or Dale Ashby and Father’s mobile recording truck. However, as I entered the room and the band stood in front of me, everything I read and researched suddenly began to come to life. As I watched Bob Livingston, Gary P. Nunn, John Inmon, and Freddie Krc, I was finally getting a glimpse of what it really meant to be a Gonzo.

The band’s setlist for the concert was a mix of Murphey’s songs, Walker’s songs, and their own personal works. They seamlessly shifted from folk, to rock, to blues, to country, picking up on each other’s non-verbal cues. In the middle of rehearsing a song, they occasionally stopped playing to tease apart a harmony or a guitar lick, and then would start up again. While the rehearsal was free-flowing and spontaneous, it was simultaneously put-together. The band mates occasionally bickered like brothers (at one point Inmon jokingly remarked that, “the Lost Gonzo Band is a band that starts every set with an argument”84), but then moments later would break out into a fit of laughter.

The following Saturday night, the Lost Gonzo Band sold out their reunion concert at Gruene Hall. The choice to reunite after years apart speaks to the band’s continued dedication to the sharing of Austin music and their passion for the art they created together. A common thread shared between concert attendees filled the room with a lively buzz, creating a warm and welcoming environment – almost resembling a family reunion. As the concert started and dancing and singing filled the space, the whole room drifted closer together, experiencing a spiritual and emotional interconnectedness. This organic, engaging musical performance, almost fifty years after the release of ¡Viva Terlingua! and Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir, further emphasizes the Lost Gonzo Band’s lasting impact on Austin’s musical legacy.

Bob Livingston, Gary P. Nunn, Craig Hillis, Herb Steiner, and Michael McGeary were rooted in vastly different worlds, which ushered a diversification of talent into the Austin music scene in the 1970s. Most of the Gonzos were not previously considered “country artists,” yet they laid the foundation for “progressive country music,” transforming the longtime understandings of the genre in the process. These folk singersongwriters, rock ‘n’ roll musicians, bluegrass players, and theater entertainers combined their knowledge and skills to create a hybrid genre of music that changed the Austin scene. As the backing band for the biggest names in Austin music, the Gonzos played a crucial role in interpreting and embellishing the compositions that singer-songwriters brought to the creative table. Their adaptability, spontaneity, and collaborative approach to music, coupled with their steadfast devotion to the local Austin music scene, made the Lost Gonzo Band creative pioneers who broke new ground to shape Austin into the “Live Music Capital of the World.”

Notes

1. Travis Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks: The Countercultural Sounds of Austin’s Progressive Country Music Scene (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 7.

2. Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks, 4.

3. Barry Shank, Dissonant Identities: The Rock ‘n’ Roll Scene in Austin, Texas (Middleton: Wesleyan University Press, 1994), 41.

4. Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks, 7.

5. Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks, 18.

6. Jan Reid, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004), 68. Eddie Wilson was the manager for Shiva’s Headband – the Vulcan’s house band – when he opened the Armadillo.

7. Cory Lock, “Counterculture Cowboys: Progressive Texas Country of the

1970s and 1980s,” Journal of Texas Music History 3, no. 1 (2003): 19.

8. The term became synonymous with “Redneck Rock,” which was coined by Jan Reid in his seminal work, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock.

9. Jan Reid quoted in Shank, Dissonant Identities, 57.

10. Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks, ix.

11. Bob Livingston, Interview by Chris Oglesby, Virtual Lubbock, December 4, 2000.

12. Bob Livingston, Interview by Chris Oglesby. A “jug band” is a band that plays with a mixture of homemade instruments and uses modified ordinary objects to make musical sounds. Examples of instruments in a jug band include washboards and spoons. The New Grutchley Go- Fastees weren’t an actual jug band, but Livingston makes the point to say they were just kids having fun and making music that was rudimentary in nature.

13. Bob Livingston, Interview by Chris Oglesby.

14. Three Faces West consisted of Ray Wylie Hubbard, Rick Fowler, and Wayne Kidd.

15. Bob Livingston, in conversation with author, November 2021.

16. Bob Livingston, in conversation with author, November 2021.

17. Bob Livingston, in conversation with author, November 2021.

18. Johnston produced Highway 61 Revisited (1965), Blonde on Blonde (1966), John Wesley Harding (1967), Nashville Skyline (1969), Self Portrait (1970) and New Morning (1970) by Bob Dylan. He produced Sounds of Silence (1966) and Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme (1966) by Simon and Garfunkel. He produced At Folsom Prison (1968), The Holy Land (1969), At San Quentin (1969), Hello, I’m Johnny Cash (1970), The Johnny Cash Show (1970), I Walk the Line (1970) and Little Fauss and Big Halsy (1971) by Johnny Cash.

19. Bob Livingston, in conversation with author, November 2021.

20. Bob Livingston, in conversation with author, November 2021.

21. Bob Livingston, in conversation with author, November 2021.

22. This is referring to the original incarnation of the Saxon Pub off of I-35 on the north side of town, as opposed to the later version that was opened on South Lamar in the 1990s.

23. Bob Livingston, in conversation with author, November 2021.

24. Gary P. Nunn, At Home with the Armadillo (Austin: Greenleaf Book Group Press, 2018), 100.

25. Nunn, At Home with the Armadillo, 118.

26. Gary P. Nunn and Bob Livingston, in conversation with author, October and November 2021.

27. Nunn, At Home with the Armadillo, 130.

28. Again, this is referring to the original incarnation of the Saxon Pub.

29. Nunn, At Home with the Armadillo, 141.

30. Craig Hillis, “The Austin Music Scene in the 1970s: Songs and Songwriters” (doctoral dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, 2011), 10.

31. According to Hillis’s dissertation, this time in England spanned the years of about 1959-1963.

32. Craig Hillis, in conversation with author, April 2021.

33. Hillis, “The Austin Music Scene in the 1970s,” 11.

34. Craig Hillis, “Steven Fromholz, Michael Martin Murphey, and Jerry Jeff Walker: Poetic in Lyric, Message, and Musical Method” in Pickers and Poets: The Ruthlessly Poetic Singer-Songwriters of Texas, ed. Craig Hillis and Craig Clifford (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2016), 61-62.

35. Hillis, Pickers and Poets, 62.

36. Hillis, “The Austin Music Scene in the 1970s,” 197.

37. Craig Hillis, in conversation with author, April 2021.

38. Gary P. Nunn, in conversation with author, October 2021.

39. Herb Steiner, interview with Avery Armstrong, February 2025.

40. The Troubadour was another club on Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood that was central to the Los Angeles music scene. Acts such as Elton John, the Eagles, and Buffalo Springfield, among others, got their starts at the Troubadour. The Monkees’ Michael Nesmith served as the M.C. there (deemed the club’s “hootmaster”) for hootenannys in the 1960s.

41. Herb Steiner, interview with Avery Armstrong, February 2025.

42. Craig Hillis, in conversation with author, April 2021.

43. Shep Cooke, “Shep Cooke Bio,” Shepcooke.com, accessed March 6, 2025, https://shepcooke.com/bio.

44. Herb Steiner, interview with Avery Armstrong, February 2025.

45. Herb Steiner, interview with Avery Armstrong, February 2025.

46. Herb Steiner, interview with Avery Armstrong, February 2025.

47. Herb Steiner, interview with Avery Armstrong, February 2025.

48. Herb Steiner, interview with Avery Armstrong, February 2025.

49. Michael McGeary, e-mail correspondence with author, January 2025.

50. Victor Molzer, “The NORAD Band: Musical Defenders,” Music Journal 26, vol. 3 (1968): 74.

51. Michael McGeary, e-mail correspondence with author, January 2025.

52. Michael McGeary, e-mail correspondence with author, January 2025.

53. Archie Green, “Austin’s Cosmic Cowboy: Words in Collision,” in And Other Neighborly Names: Social Process and Cultural Image in Texas Folklore, ed. Richard Bauman and Roger D. Abrahams (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 173.

54. For the sake of this article, I will continue to refer to Murphey’s band as the “Austin Interchangeable Band,” although this was never their official name; rather, this was the name that points to the larger group of flexible, dependable Austin musicians, which includes Murphey’s band among others. According to Craig Hillis’s dissertation and Jerry Jeff Walker’s autobiography, Steven Fromholz came up with the name to describe the group of musicians in the early 1970s. The name of Murphey’s specific group of musicians changed over time, but was commonly referred to as the “Cosmic Cowboy Orchestra.”

55. Jerry Jeff Walker, Gypsy Songman (Duane Press, 1999), 113.

56. Walker, Gypsy Songman, 113.

57. Bob Livingston, in conversation with author, November 2021.

58. Kelly Dunn played B3 organ on this recording.

59. Ed Smykus, “Viva Jerry Jeff!,” The Tab (1994), Box 5, Folder 2, Jerry Jeff Walker Collection, Wittliff Collections, Texas State University.

60. Gary P. Nunn, At Home with the Armadillo, 157

61. Bob Livingston quoted in Richard Skanse, “A Man Must Carry On,” Texas Music Magazine, Spring 2004.

62. Tape #006, “Dale Ashby and Father Mobile, Luckenbach, Texas,” August 16, 1973, audio recording, Jerry Jeff Walker Collection, Wittliff Collections, Texas State University.

63. Craig Hillis, in conversation with author, April 2021.

64. Tape #005, “5B Live” (Dale Ashby and Father Mobile, Luckenbach, Texas), August 16, 1973, audio recording, Jerry Jeff Walker Collection, Wittliff Collections, Texas State University.

65. Reid, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock, 105.

66. Jeff Gage, “Jerry Jeff Walker’s ‘Viva Terlingua’: Inside the Fringe Country Album,” Rolling Stone (2020), https://www.rollingstone.com/feature/viva-terlingua-jerry-jeffwalker-outlaw-country-772406/

67. Prior to the official naming of the Lost Gonzo Band, Bob Livingston notes that he would introduce the band with a different name every time they performed. Some examples he gave in an interview were “Jerry Jeff Walker and the Unborn Calves,” “Jerry Jeff Walker and the Rodeo-deo Riff-Raffs,” and “Jerry Jeff Walker and the Bluebonic Plague.”

68. Steven L. Davis, Texas Literary Outlaws: Six Writers in the Sixties and Beyond (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 2004), 299. For more information on Gonzo journalism and Austin’s Mad Dogs, see Clay Smith, “Notes on Mad Dogs: On Being Young, Talented, and Slightly Insane in Old Austin,” The Austin Chronicle, January 26, 2001. https://www.austinchronicle.com/books/2001-01-26/80284/.

69. Walker, Gypsy Songman, 126.

70. Gary P. Nunn, in conversation with author, October 2021.

71. John Inmon, in conversation with author, February 2022.

72. David Stone, “John Inmon: Gober to Gruene Hall,” Our Town Temple, July 9, 2022, https://www.ourtowntempletx.com/p/john-inmon-goberto-gruene-hall.

73. John Inmon, in conversation with author, February 2022.

74. John Inmon, in conversation with author, February 2022.

75. John Inmon, in conversation with author, February 2022.

76. Stone, “John Inmon: Gober to Gruene Hall.”

77. Stone, “John Inmon: Gober to Gruene Hall.”

78. Terry Hagerty, “‘Cosmic Cowboy’ guitarist John Inmon continues storied career in Bastrop,” Austin American Statesman (Austin, TX), June 18, 2021.

79. Freddie Krc, in conversation with author, September 2022.

80. Freddie Krc, in conversation with author, September 2022.

81. Freddie Krc, in conversation with author, September 2022.

82. Freddie Krc, in conversation with author, September 2022.

83. Freddie Krc, in conversation with author, September 2022.

84. John Inmon, quote from Lost Gonzo Band rehearsal, as observed by author, October 2021.