Golly Gee: The Short but Exciting History of Chicano Soul Music in Texas,

1954-1969

Guadalupe San Miguel, Jr.

Música Tejana has been an important aspect of Mexican American cultural traditions for decades.

The historical consensus pioneered by Manuel Peña holds that since the early 1900s, this music has been played by two major ensembles- the orquesta and the conjunto. During the 1950s and 1960s, música tejana experienced significant changes and new ensembles emerged to play the music loved by its fans. During these years, for instance, musicians added new rhythms, instruments, and vocal styles to the existing ensembles. Tejano and Tejana musicians also created at least four new distinct ensembles that played this type of music and that competed for the hearts and minds of its fans: Chicano soul groups, grupos Tejanos, Chicano country bands, and progressive conjuntos. The following narrates the brief history of one of these new ensembles—the Chicano soul group. It describes its origins in the mid-1950s, its growth in the next decade, and its decline by the late 1960s.

During the 1950s, many Mexican American teenagers lived in segregated urban and rural communities throughout the state. Despite their physical isolation from Anglo America, the vast majority of them were exposed to many of the social and cultural changes taking place in the United States. Of particular importance was their exposure to consumer culture in general and more specifically to various forms of American music, especially blues, rhythm ‘n’ blues (R&B), rock ‘n’ roll, and country music. Young aspiring musicians fell in love with the new sounds they heard in their communities and initially wanted to add rock ‘n’ roll licks or rhythms to música tejana in order to make it more appealing to young people. The vast majority however simply wanted to play these exciting rhythms to whoever would listen to them.1

The recording and performing of rock ‘n’ roll or R&B by Chicano youth during the 1950s and early 60s was not an isolated development but a regional one found throughout the Southwest.2 Chicano soul and rock ‘n’ roll groups formed in southern California, in several parts of Texas, and in a few cities in Arizona and New Mexico. These areas generally contained significant numbers of Mexican origin individuals. In Texas, Mexican American soul groups emerged in five distinct areas of the state: San Antonio, South Texas, El Paso, Central Texas, and Houston.3

In Texas, Chicano soul originated with a few conjunto groups playing rock ‘n’ roll in the mid-1950s. Three conjuntos in central Texas played key roles in adding rock ‘n’ roll rhythms to their repertoire in this decade—David Coronado and the Latinaires (Temple), Armando y Conjunto México (San Antonio), and Conjunto Los Panchitos (San Antonio). David Coronado, Jr. headed the Latinaires in the mid-50s. He grew up thirty miles south of Temple and came from a musically inclined family that lived in a poor segregated Mexican American neighborhood. From a young age, Coronado loved all types of music and devoted himself to getting a musical education. “So I studied Bob Wills and Lawrence Welk records. I learned jazz, I learned hillbilly and some pop,” Coronado noted. “I was like a sponge. I absorbed all the data (music) and stored it in my memory bank to draw from in the future.”4

Although he loved Mexican music and played with a few orquestas tejanas, he wanted to “get away” from the polkas and the big band sound. He wanted to be modern and play rock ‘n’ roll. In 1954, he formed a four-member combo comprised of himself (saxophone), Joe Hernández (guitar), Jacinto Rángel “Cino” Moreno, Jr. (drums), and Tony “Foreman” Matamoros (saxophone).5 He named the group the Latinaires. When asked about the name Coronado responded that some of the more popular groups of the day were the Bel-Aires, the Corvairs, and the Jordanaires. “So why not the Latinaires we asked ourselves? We were all Chicanos, were all of Latin descent—Italian, Spanish, and Mexican with some European blood,” he said.6

Once formed the group was ready to “shake, rattle, plus rock ‘n’ roll the polkas.”7 The Latinaires turned standard Mexican rancheras into “funky dance tunes.” In other words, they made Mexican music cool for youth audiences by adding rock ‘n’ roll licks to the rancheras. The group also played popular English-language music that appealed to the new generation of Mexican Americans.

Two conjunto musicians from San Antonio also played a key role in advancing Chicano soul during the mid-1950s. One of these was Armando Cavallero “Mando” Almendárez. He headed Conjunto México and played traditional Mexican music. Like other Mexican American teenagers he loved R&B and began to record Chuck Berry tunes but with an accordion and upright bass. In 1956, he changed the name of the group to Mando and the Chili Peppers. For the next several years the Chili Peppers recorded a series of rock ‘n’ roll tunes that reflected the tastes of the new generation in that city. Rudy Trevino Gonzales, in 1955, headed Conjunto Los Panchitos. Sometime in the late 1950s he heard James Brown and quickly began to perform R&B. “When I first heard James Brown in 1957 or 1958, no hombre! I used to imitate him to the tee.” Gonzales soon changed the name of the group to Rudy T. and the Reno Bops and became one of the most well-known R&B groups in the San Antonio area.8 His recording of “Cry, Cry” (Rio R-101) became a Chicano soul classic in San Antonio during the late 1950s.9

A few individuals and orquestas in South Texas likewise played rock ‘n’ roll or incorporated it into their rancheras in this decade. The Freddie Martinez Orquesta from Corpus Christi, for instance, recorded a rock ‘n’ roll song called “Walking the Dog” around 1957. Isidro Lopez from Corpus Christi also recorded what he called a “rock ranchera” in 1957. It was titled “Mala Cara.”10 “Why not take the first step in injecting rock and roll bars into a Mexican tune?,” he noted many years later.11 During the same year singer Baldemar Huerta from San Benito recorded two rock ‘n‘ roll and one country and western song in Spanish: “No Seas Cruel,” a Spanish-language version of Elvis Presley’s “Don’t Be Cruel”; “Jamaica Farewell,” a Harry Belafonte song; and “Tu Frio Corazón (Cold, Cold Heart),” a Hank Williams song. In this year he was known as el Bebop Kid. He later changed his name to Freddy Fender.12

The trend towards recording rock ‘n’ roll and R&B in this period attests to the impact that various styles of American music were having on the younger generation of Chicanos born and raised in the U.S. It also shows the continuing cross-fertilization or blending of Mexican music with popular music. In earlier decades, Tejano musicians played rancheras and polkas and incorporated Latin rhythms, big band music, jazz, and top 40 sounds. Beginning in the 1950s, the younger generation turned to the new sounds popular in the United States and Mexico in this decade. While the dominant influence on these musicians was rock ‘n’ roll during the mid- 1950s, other styles like R&B, doo-wop, and country would be embraced by Mexican American teenagers by the end of the decade and into the 1960s.

While these young Tejano musicians of the mid-1950s did not have any major hits, they inspired other youth to form their own groups throughout the state. The following table, while incomplete, shows the vast number of Chicano soul groups that formed in different parts of the state during the late 1950s and in the 1960s.

Select List of Tejano soul groups by region, 1950s-1960s

San Antonio

The Galaxies

The Sunglows

The Lyrics (with Dimas Garza)

The Kool Dips

Sunny and the Sunliners

Sonny Ace and the Twisters

Charlie and the Jives

Randy Garibay and the Pharoahs

Tito and the Silhouettes

The Dell-Kings

The Royal Jesters

Rudy T. and the Reno Bops

Doug Sahm

Henry (“Pepsi” Peña) and the Kasuals

Danny and the Dreamers

The Lovells

The Playboys

Dino and the Dell-Tones

Central Texas

David Coronado and the Latinaires (Temple)

Cruz Ortiz and the Flames (Waco)

Little Joe and the Latinaires (Temple)

Junior and the Starlites/Latinglows (Dallas/Ft Worth)

Broken Hearts (Seguin)

Dominoes (Austin)

Cisco Rangel y Los Jesters (Austin)

Fred Salas y Los Latinos (Austin)

South Texas

Freddy Fender (San Benito)

Noe Pro and the Valiants (Brownsville)

Johnny Jay and the Pompadours (Valley)

The Prophets (Valley)

Ray Camacho (Valley)

Carlos Landin and the Rondels (Laredo)

Los Peppers de Victor Garza (Laredo)

Noe Pro (Corpus)

Bobby Galvan Orchestra (Corpus)

Oscar Martinez Orchestra (Corpus)

Freddie Martinez Orchestra (Corpus)

Los Dinos (Corpus)

George Jay and the Rockin’ Ravens (Corpus)

Rick Cantu and the Rockin’ Dominoes (Corpus)

Ricky G. and the Dreamglows (Taft)

Ram and Henry (Robstown)

El Paso

Bobby and the El Paso Premiers

The Jives

Houston

Little Jesse and the Rockin’ Vees

Jesse Casas and the Crystals/Stardusters

Manuel (Mendiola) and The Exiles

Johnny and the Del-Hearts

Rick Vee and the Stardusters

Neto Perez and the Originals

Big Lu y los Muchachos

Rock Gil and the Bishops13

Different types of Chicano soul groups formed in the late 1950s and 1960s. The most common was probably the R&B combo. Combos were initially small and comprised of a vocalist and a few musicians playing three or four instruments—a drum set, an electric guitar, a saxophone, and, at times, an electric bass. The vast majority of combos played either rock n’ roll or R&B. What mattered was the music, not the label. Two examples of small combos were Tito and the Silhouettes from San Antonio and David Coronado and the Latinaires from Temple. The latter, as noted earlier, was formed in 1954 and comprised of Coronado and three other musicians playing an electric guitar, a drum, and two saxophones.14 The Silhouettes formed in 1956. The group comprised of four individuals: a vocalist, a guitar player, a drummer, and a saxophone player.15

R&B combos did not remain small. By the end of the decade, they expanded as musicians added more instruments. Most, for instance, added either an electric bass, an additional saxophone, or an organ to the existing ensemble. Pictorial evidence, for instance, shows that Al and the Exclusives from San Antonio by the late 1950s had five instruments in his group: a drum, an electric guitar, an electric bass, a saxophone, and a small piano.16 The Dell-Kings and the Satin Souls from San Antonio had an electric guitar, a bass, a drum set, and at least two saxophones in their group by the late 1950s.17

Musicians kept adding new instruments and vocalists to their groups, and by the mid-1960s they became full-fledged orquestas. Among some of the combos that transitioned to Chicano soul orquestas by the mid and late 1960s were the Sunglows (San Antonio), the Latinaires (Waco), Little Henry and the Laveers (San Antonio), and Junior and the Starlites (Waco). By 1964, for example, the Sunglows was a seven-piece band with two horns, drums, bass, guitar, organ, and one vocalist, Joe Bravo. The Latinaires, now under the leadership of Little Joe, was comprised of twelve members in the mid- 60s: nine musicians and three vocalists.18 Although similar in size to the orquestas of Isidro Lopez and Eugenio Gutierrez, the new generation tended to play mostly Chicano soul.

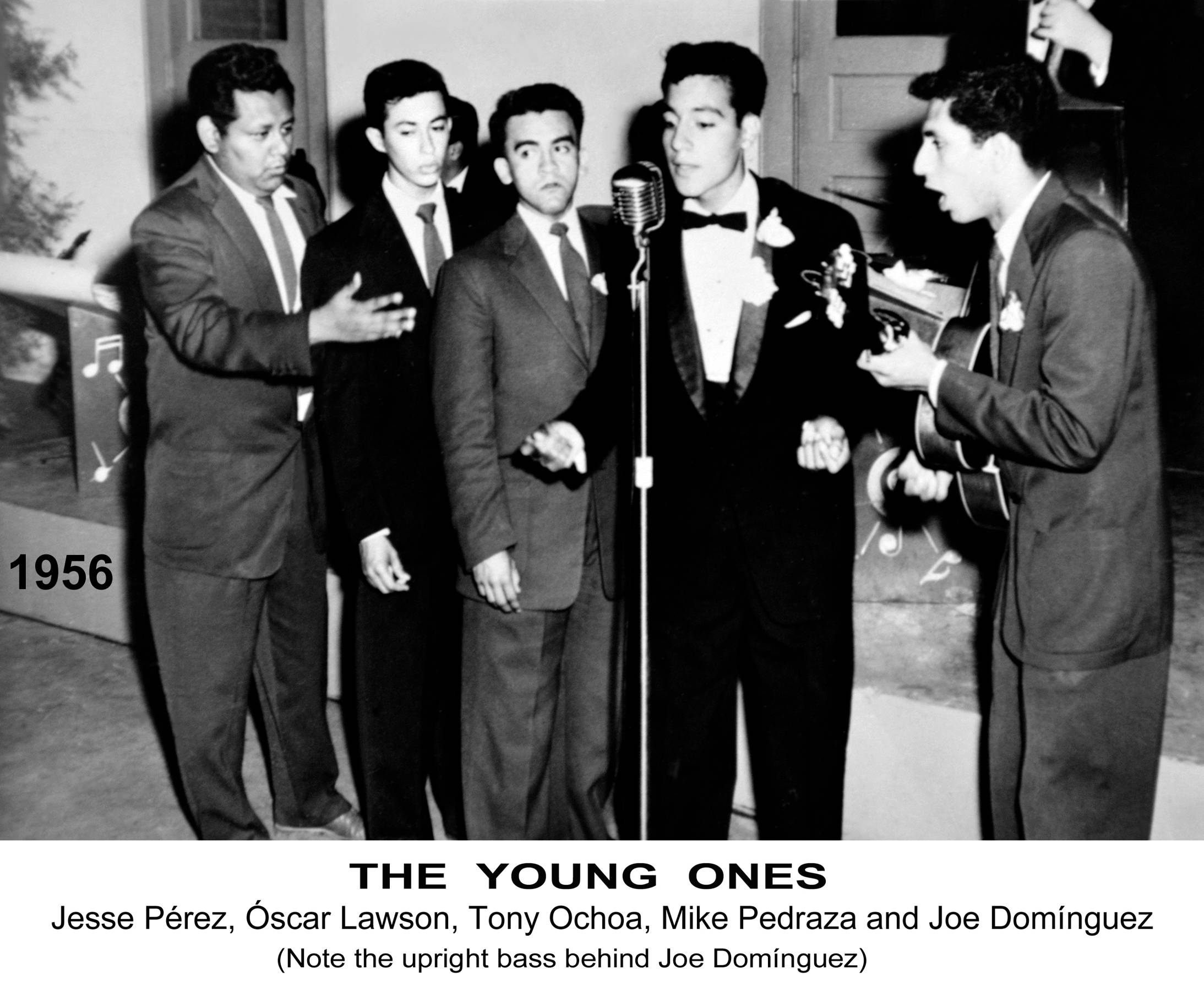

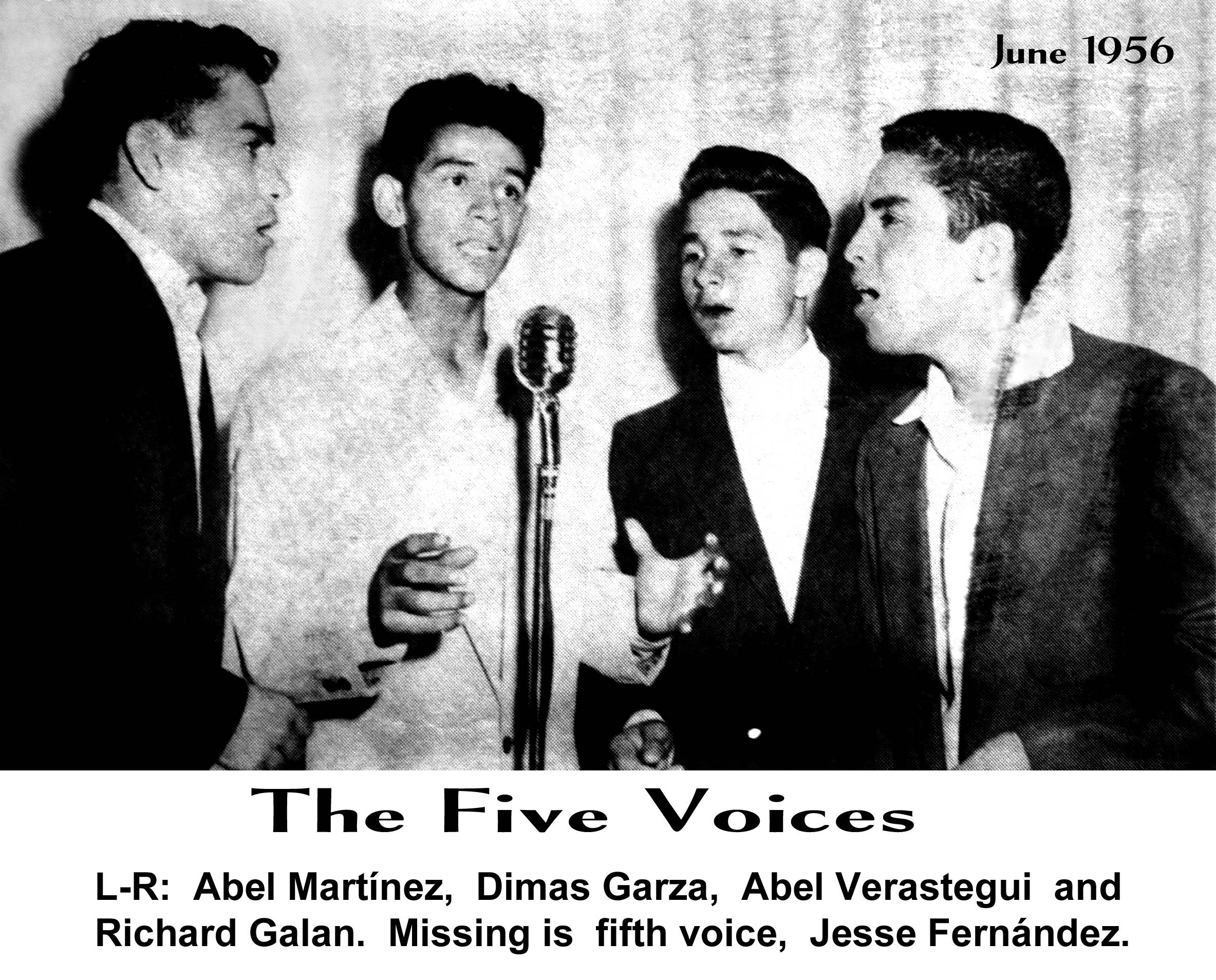

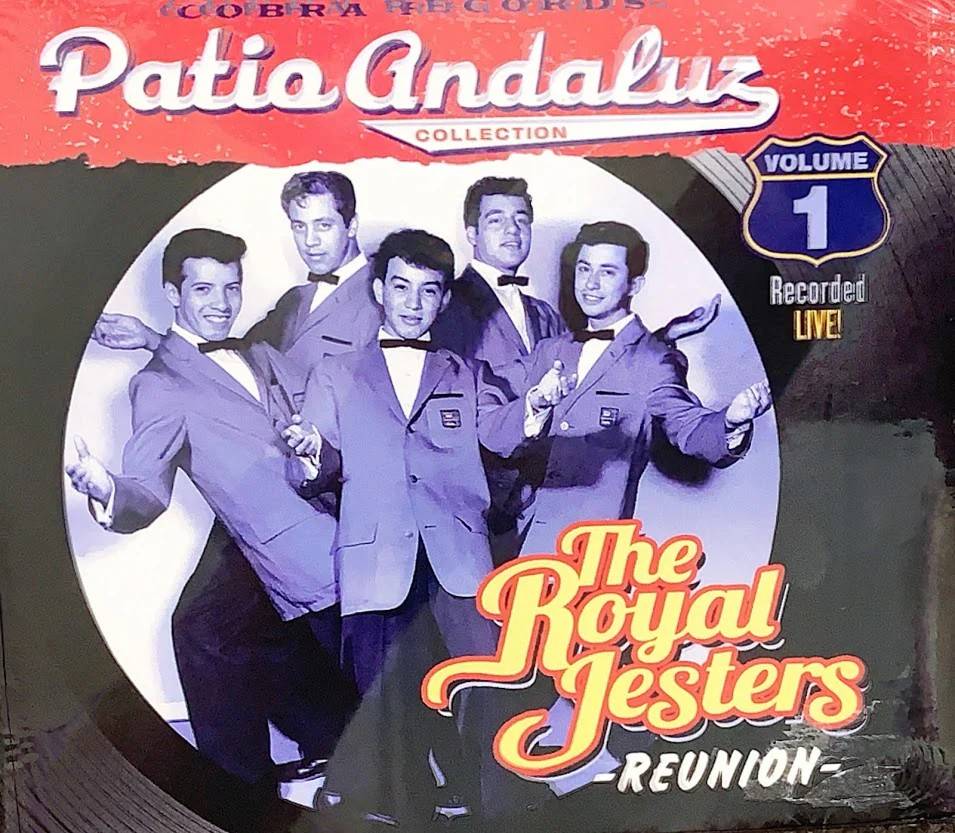

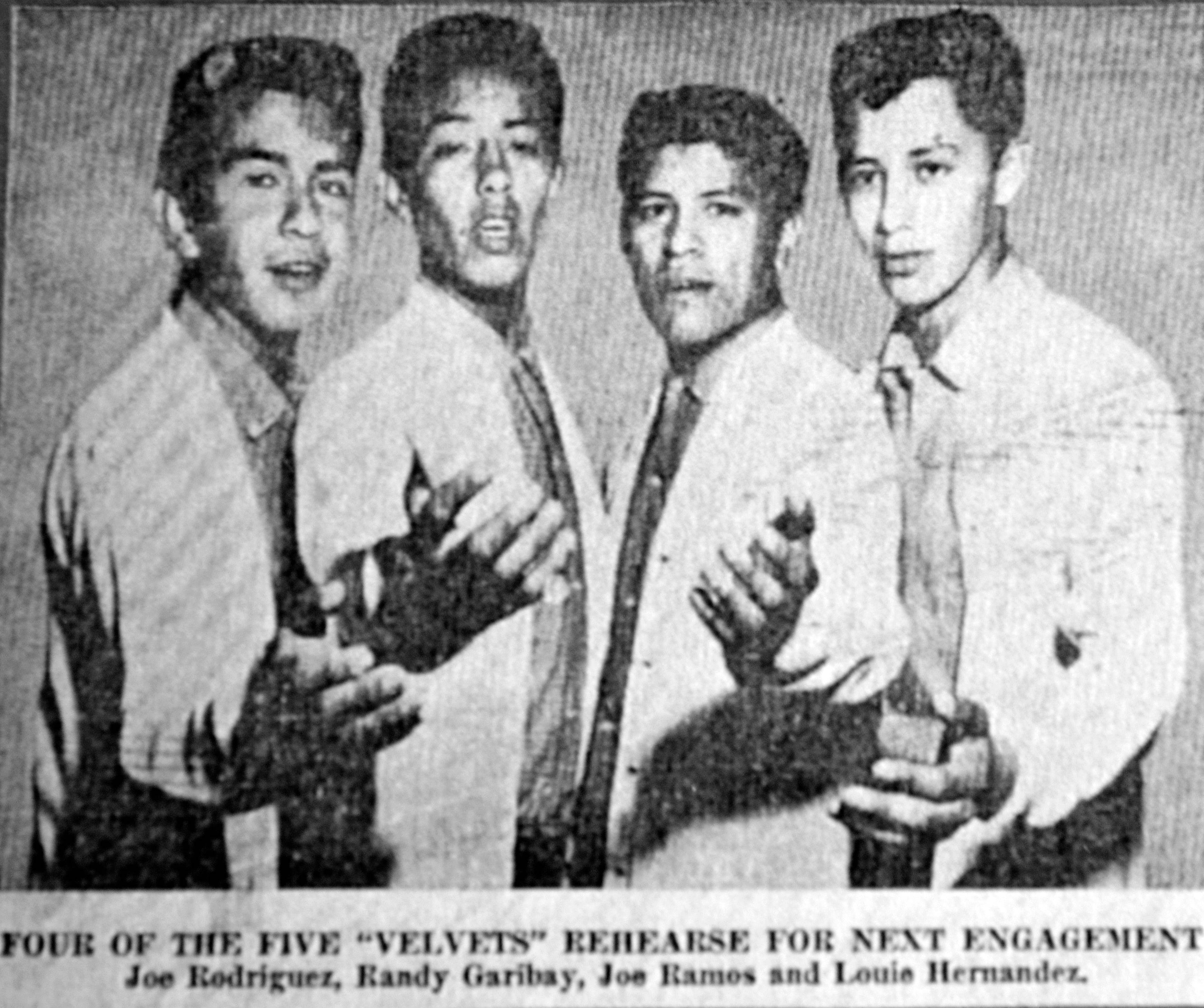

Another type of group popular during the 1950s and 1960s was the vocal harmony or doo-wop group. Most of the groups formed during these years were all-male, although a few mixed groups and all-female groups were established. Some of the all-male doo-wop groups found in various cities were the Gumdrops (Corpus Christi), the Dinos (Corpus Christi), the Five Angels (San Antonio), the Kool Dips (San Antonio), the Rhythmaires (Rio Grande Valley), the Velvets (San Antonio), the Young Ones (San Antonio), the Galaxies (San Antonio), the Five Voices (San Antonio), and the Royal Jesters (San Antonio).19

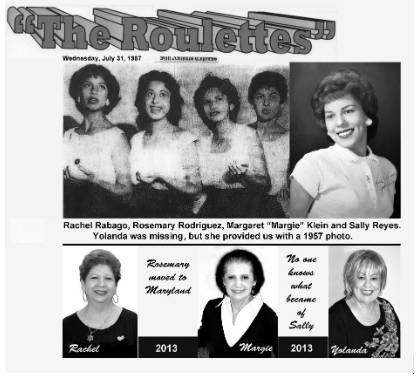

The first all-female vocal group, The Roulettes, formed in San Antonio in 1956. This group was comprised of lead vocalist Yolanda Garibay, Rachel Rabago, Margie Klein, Sally Reyes, and sisters Rosemary and Sylvia Rodríguez. Pete Villasenor, a pianist, provided the musical backing to this group. The Roulettes were inspired by Yolanda’s brother, Randy Garibay, a musician who formed several doo-wop groups during these years, including the Spinners in 1955, the Velvets in 1956, and the Pharaohs several years later. Both Yolanda and Randy themselves came from musical families and played key roles in Chicano soul during these years. The Roulettes played at several venues throughout the city and appeared on a KCOR-TV show known as The Scratch Phillips Show but did not get to record a single. The group broke up by 1958.20

After the Roulettes disbanded, several other young women formed the Uniques. Those involved in the formation of the group were Rachel “Rae” Rabago (now Longoria), Oralia Delgado and her sister Dolores Delgado, and Linda Rose Farías (now Garza) on piano and occasional backup vocals. Unlike the Roulettes, the Uniques soon recorded a vinyl single that garnered national attention. Hoping to make it big in the national market, the group left San Antonio and moved to California.21

As mentioned above most of the doo-wop groups were male. The majority of them formed in San Antonio, but others originated in places like Corpus Christi, Odessa, and Victoria.22 Two of the most well-known harmony vocal groups to form during the 1950s were the Royal Jesters from San Antonio and the Dinos from Corpus Christi. The former group, formed in 1958, was originally comprised of Mike Pedraza, Oscar Lawson, Henry Hernandez, and Louis Escalante. All of them attended Lanier High School in San Antonio’s westside. When asked why they chose the name, Henry Hernandez responded:

“Well during that time there was the Royal Days, royal this, royal that. A couple of us said, ‘Let’s call it the Royals. Others said, ‘No, let’s call it the Jesters… that’s how we came up with the name.”23

When asked what type of music they wanted to play Oscar Lawson said:

“The Royal Jesters came together specifically to perform English rhythm and blues, mainly the Motown Sound. We based our harmonies on the Mexican trios like Los Tres Diamantes, Los Tres Aces, and Los Panchos, which were very similar to the group harmony sound we were listening to on the radio.”24

The Dinos were similarly inspired by the R&B sounds and the vocal harmony groups of the 1950s. This group was formed in Corpus Christi by three individuals-Abraham Isaa Quintanilla Jr, Bobby Lira, and Seff Perales. The Dinos popularized R&B sounds in South Texas and for a number of years played in various venues throughout the southern part of the state.25

Most doo-wop groups initially did not have a band. Other R&B groups backed them up in their performances or on their recordings. By the early 1960s, however, the doo-wop groups began to have their own bands. As alluded to above, doo-wop groups were influenced by popular music in both the United States and Mexico. Female doo-wop groups were most likely influenced by groups such as the Shirelles and the Chantels.26 Some of the all-male doo wop artists were influenced by Black harmony groups like the O’Jays or the Temptations, while others incorporated the style of singing popularized by Mexican trios such as Los Tres Diamantes and Trio Los Panchos.27

Tejano soul music was quite diverse during the 1950s and 1960s. Some of the soul groups, like the Sunliners, had crooners like Sunny Ozuna and sang bluesy ballads. Others like Charlie and the Jives or Mando and the Chili Peppers rocked the night away with higher-tempo numbers. Most of the groups utilized a variety of instruments for their sound and either emphasized a specific instrument like the guitar or the saxophone or blended various instruments to create a sound that appealed to Mexican American teenagers. Despite the diversity of styles, one particular sound dominated, especially in San Antonio. Many artists referred to this style as either the Westside sound (i.e., music developed by musicians residing in the Westside of town) or more generally the San Antonio sound.28 The “Westside sound” was the music that emerged from the combined use of a particular type of organ and a horn section comprised of two or more saxophones. Although R&B groups used other instruments, the sounds made by the organ and the pitos (horns) were the most prominent ingredients in Chicano soul music during these years.29

The first major ingredient of the Chicano soul sound was the horn section, especially the use of the saxophone. Saxophones were quite common in música tejana. Orquestas tejanas of the post-WWII years, for instance, utilized the saxophone in their ensemble to play their polkas and rancheras. The new generation of musicians, however, was not interested in the use of the saxophone in combination with other wind instruments. It also wanted to play the saxophone differently than the older generation. Mexican American teenagers wanted to play the blues and rock ‘n’ roll with the saxophone, not polkas and rancheras. Their musical icons were not Villa or Lopez but Big Joe Turner, T-Bone Walker, Junior Walker, Big Jay McNeely, and Chuck Higgins. These Black artists utilized the saxophone to inject incredible energy and excitement to their songs. The use of the saxophone by the current R&B artists, in many cases, led to “fingerpopping” times, as noted in one of Hank Ballard’s songs.30 Most Chicano soul bands were interested in sounding like their favorite R&B artists and thus formed groups with at least one or two saxes in their ensemble.31 Two of the earliest groups formed with one saxophone were Al and the Exclusives and Tito and the Silhouettes, both from San Antonio.32 The majority of the groups had two saxophones. The Dell-Kings, Sonny Ace, Charlie and the Jives, and the Sunglows, all from San Antonio, for instance, had two saxophones.33 This dual horn section, which some individuals referred to as the “Westside” horns, became the dominant sound heard in San Antonio-based Chicano soul.

The adoption of an enlarged horn section among Chicano soul groups was not limited to San Antonio. Photographic and oral history evidence indicates, for instance, that David Coronado and the Latinaires, which later became Little Joe and the Latinaires, also had two saxophones when formed and then added a few more pitos by the end of the decade. The Latinaires, formed in Temple in 1954, and were not aware of developments in San Antonio until a few years later.34 The trend towards expanding the horn section in R&B combos can probably be attributed to the general impact that Motown, the Memphis sound, doo-wop, and other forms of R&B were having on Chicano music in the 1950s and 1960s.

The second major ingredient of the Westside sound was the organ. The electric organ was a relatively new musical instrument for such combos, and it replaced the piano in many blues and R&B groups during the late 1950s and 1960s. Different types of organs existed, but the historian Ruben Molina argues that by the mid-60s the Hammond B3 became the one that most Chicano soul groups incorporated into their ensemble. Molina credits Manuel Guerra, Sunny's drummer, for introducing the Hammond B3 organ to San Antonio’s soul music. Guerra, who had played with the Isidro López’s orquesta, wanted to emulate the accordion used in conjunto music but with the organ. According to one source, the Hammond B3 organ was capable of doing this. It was extremely versatile and could produce melodies, chords, and a large number of additional sonic sounds.35 Guitarist Bobby Galvan of Danny and the Dreamers, on the other hand, argues that San Antonio musicians incorporated the organ because of the impact that the Memphis sound had on them.36 The Memphis sound, initiated by Stax Records in Tennessee, played soul music punctuated by the dominant sounds of the organ and a horn section comprised of two saxophones and one trumpet. Prominent artists recorded by Stax Records were the Mar-Keys, Booker T. & the MGs, and Otis Redding.37

The expanded horn section and the organ in combination with the electric guitar, the electric bass, and the drums completed the Chicano soul ensemble. The unique sounds made by these instruments, especially the combined use of the Hammond B3 organ and the pitos, was a dominant strand of Chicano soul during the 1960s.

Two groups were instrumental in the dominance of the San Antonio sound in Tejano soul, Sunny Ozuna from San Antonio and Little Joe Hernandez from Temple. Sunny’s full name is Ildefonso Fraga Ozuna. He came to be known as Sunny once he formed his first group in high school. Ozuna was born in San Antonio in 1943 and came from a large family residing in an extremely poor neighborhood on the south side of town. Although he heard Mexican American music while growing up, he, like other local Tejanos, enjoyed and played mostly R&B music in the late 1950s. Ozuna’s first group, the Sunglows, consisted of five individuals: two Mexican Americans, two Anglo Americans, and one African American. Norwood Perry played the electric bass, Al Condy the guitar, George Strickland the drums, and Rudy Guerra the saxophone. Sunny sang.38 From 1958 to 1963, the Sunglows had several hits, including “Talk to Me.” This song earned him an appearance on the popular television show American Bandstand.39 By the early 1960s, Sunny’s band was probably the most successful Tejano R&B group in San Antonio.

His influence increased significantly after 1963. In this year, he left the Sunglows and formed another band. The Sunliners, as it came to be known, included several new top-notch musicians and an expanded horn section. The new members included Arturo “Sauce” Gonzales (keyboard), Rudy Palacios (guitar), Chente Montes (bass), and Armando Alba (drums). The horn section of the new group also expanded from two to five. The original Sunglows in the mid-1950s began with one saxophone and quickly expanded to two.40 The use of twin saxes by other local R&B groups encouraged Sunny to add a second one to his group by the early 1960s. In 1963, Sunny expanded the horn section further. The horn section was led by Rudy Guerra (alto sax) and included Johnny Garcia (tenor sax), Charlie McBurney or George Morin (trumpet), and Jay Johnson (trombone). Sunny also added a Hammond B3 organ. The introduction of this particular keyboard to Sunny’s group was Rudy Guerra’s idea. This instrument, unlike other keyboards used by R&B groups, had a fuller sound and was more versatile. Finally, Sunny, unlike many R&B groups, recorded Mexican polkas and rancheras, not only R&B. He had hits in both the English- and Spanish-speaking markets. The enhanced Westside sound (i.e., the expansion of the horn section in combination with the use of the Hammond B3 organ), the recruitment of top-notch musicians, and the soulful voice of Sunny Ozuna singing in English and Spanish made his what Molina called the “premier” Chicano group in the country by the mid-1960s.41 The unique blend of sounds created by the Sunny and the Sunliners band likewise set the standard for all other groups throughout the state. Soon Tejano soul groups in San Antonio and throughout Texas emulated the big brassy sound of Sunny’s band.42

Another extremely influential Tejano soul group was David Coronado and the Latinaires, later known as Little Joe and the Latinaires. This group was from Temple, Texas.43 Unlike many of the soul groups in San Antonio, the Latinaires played mostly conjunto music but with touches of R&B. Coronado left the group in 1958, and Little Joe and his brother Jesse took over. Little Joe’s brothers Johnny and Rocky soon joined, and the band’s name was changed to Little Joe and the Latinaires.44

Like Sunny, Little Joe incorporated the San Antonio sound into his music. He, in other words, had a large horn section and utilized it in combination with the Hammond B3 organ. He also performed Mexican rancheras and various forms of American music such as R&B, soul, rock ‘n’ roll, country, and jazz. Similar to other Tejano soul groups, Little Joe recorded for a variety of local companies.

Although he and Sunny were major competitors for decades, Little Joe’s style was very different from the Sunliners and soon began to appeal to large numbers of fans throughout the state and nation. In the 1960s, his music was a great combination of Mexican, Motown, Memphis soul, R&B, and country styles. By the end of the decade, Little Joe was also effectively incorporating jazz and blues into his polkas and was known for doing a blood-curdling grito in all his shows. The San Antonio sound, the great musicians he hired, and Little Joe’s vocals led to the recording of countless Spanish and English hits during the 1960s and for many decades thereafter.

Sunny and Little Joe influenced large numbers of Mexican American teenagers to form their own groups throughout the state. They planted what one historian referred to as “seeds” of musicians who grew up to sound very similar to them. Sunny best expressed the impact they had on Mexican American teenagers in the 1960s when he said:

“The local teens would get enthused (about our music) and they would go out and start a group and it spread. Then maybe the next time we’d go back to Albuquerque, or El Paso, or even in Wisconsin they would say ‘Yea we have some groups like you guys, we have so and so and so and so.”45

The growth of Chicano soul groups during the 1960s was rapid and widespread. Keep in mind that while each group had a distinct sound, by the late 1960s the vast majority of them emulated Sunny and Little Joe. Some of these groups lasted a few months or a few years while others lasted for decades.

Although dynamic, the Chicano soul movement began to wane by the late 1960s as musicians transitioned to la Onda Chicana.46 During the late 1960s, musical and political conditions changed dramatically. Among other factors, the British Invasion introduced stiff competition into the mainstream music industry and also encouraged a few Chicano groups to abandon the English market and to embrace Mexican music. Two of the most influential groups in Chicano soul, Sunny and the Sunliners and Little Joe and the Latinaires, led the movement away from R&B in the mid- 1960s. Sunny once remarked how difficult it was to remain popular in the English market. “I lived in that jungle (top forty market) for a while and I didn’t like it,” he said. “I’m not saying that I wouldn’t like to have another ‘Talk to Me,’ and make the money that comes of it, but it’s a jungle,” he added. “You have friends and money only while you’re there. The minute that song dies, ‘Sunny who?’” he further commented.47 Little Joe, unlike Sunny, never did crack the top forty market although as he noted “that was everybody’s dream.”48 Unable to effectively compete in the English-language market, Little Joe and Sunny turned to the traditional Tejano market. After 1965, they focused on playing mostly Mexican rancheras and polkas. In their view the Tejano market was more accepting and supportive of their musicians even if they did not have any hits. “Chicanos hold on to their roots, and hold on more to their stars,” Sunny once remarked. “They back them better,” he added.49

Another reason for the decline of Chicano soul in Texas was the emerging Chicano movement. Increased pride in ethnicity among Chicanos in the United States and a growing movement towards activism encouraged young people in general and Chicano soul musicians in particular to leave R&B behind. Rather than emphasize English-language music, many groups, in keeping with the nationalist movement, began to focus on playing mostly Mexican music but with soul.50

The transition away from R&B and towards Mexican music was reflected in the first albums recorded by Sunny and Little Joe. Sunny’s first album, recorded in 1965, was Cariño Nuevo. Little Joe recorded his first album, Por Un Amor, in 1964. Both these albums featured only Mexican rancheras and polkas, no R&B or rock ‘n’ roll. Although no English songs were recorded, Sunny and Little Joe retained the San Antonio sound and played Mexican music with Chicano soul. In doing so, they initiated a new sound in música tejana and gave birth to La Onda Chicana.51

Sunny’s and Little Joe’s decision to “go Chicano,” that is, to record mostly Mexican music, had a significant impact on the majority of Chicano soul groups in the state. Gradually, the vast majority of them made the switch away from Chicano soul to La Onda Chicana. Vic Love, a soul singer from San Antonio, recalled this transition away from R&B and towards Mexican music. In 1969, he was playing with the Lovells. The group recorded a couple of Spanish and English singles and toured throughout the state. He noted however that by 1969 people in Waco, Corpus Christi, and Houston were not interested in the English tunes. “The crowds that we played for wanted Spanish polkas,” he said. “Although we did play some English stuff, I don’t think that was the reason they came to see us,” he added. These crowds, in other words, wanted to hear Mexican music, not R&B. The Chicano soul era, as experienced by Vic Love, was coming to an end and a new one, La Onda Chicana, was emerging.52

Notes

1. For a brief overview of the context of the 1950s and the desire by Mexican American teenagers to play rock ‘n’ roll or to use it to spruce up Mexican polkas and rancheras see Ruben Molina, Chicano Soul: Recordings and History of an American Culture (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2017), 21-44; 83-105; and The Latinaires, La Familia, Little Joe y más, As told to Ramón Hernández (San Antonio: Hispanic Entertainment Archives Publishing, n.d.), 52-60. For the excitement generated by R&B and rock ‘n’ roll among Chicanos in California during the same period see David Reyes and Tom Waldman, Land of a Thousand Dances: Chicano Rock ‘n’ Roll from Southern California, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998), 11-17.

2. For more information on the Chicano soul movement in San Antonio see “West Side Sound,” Handbook of Texas Online, tshaonline.org. For one of the founders of this style of music see “Morales, Eracleo Mario [Rocky]”, Handbook of Texas Online (tshaonline.org).

3. Molina also notes that Tejano musicians influenced rock and roll groups like ? and the Mysterians and Sam the Sham and the Pharoahs. See Ruben Molina, Chicano Soul: Recordings and History of an American Culture (Lubbock, Tx: Texas Tech University Press, 2017), 83-104.

4. Hernández, 46-47.

5. Hernández, 46-50. Joe Hernandez later assumed leadership of the group and renamed it Little Joe and the Latinaires.

6. Hernández, 53.

7. Hernández, 54.

8. Molina, 24.

9. Hernández, 59.

10. Mala Cara, Strachwitz Frontera Collection, University of California, Los Angeles. Recorded in 1958.

11. Hernández, 40.

12. Freddy Fender was born and raised in San Benito, Texas. He grew up listening to Mexican and American music along the U.S.-Mexico border during the late 1940s and by the 1950s began to record rock and roll songs in Spanish.

13. Author personal knowledge; Molina, 2017.

14. Hernández, 53.

15. See picture of group in Molina, 24.

16. Molina, 22.

17. Molina, 26-27.

18. Molina, 29, 88.

19. A longer list of doo-wop and R&B group can be found in Ramon Hernandez, “Notes-Doo Wop Groups,” unpublished document, Ramón Hernández Archives, San Antonio, Texas.

20. Ramón Hernández, "Whatever Happened to The Roulettes? San Antonio’s First All-Girl Vocal Group,” unpublished article. Ramón Hernández Archives, San Antonio, Texas.

21. Ramón Hernández, “The Uniques: The First Mexican American Girl Group in the U.S.A.,” unpublished article. Ramón Hernández Archives, San Antonio, Texas.

22. For a comprehensive list of Chicano soul group in the 1950s and 1960s see “Notes Doo Wop Groups,” unpublished document, Ramón Hernández Archives, San Antonio, Texas.

23. Ryan Boyle, “The Royal Jesters: From First to Final Valentine’s,” Numero Group, https://numerogroup.com/blogs/stories/the-royal-jesters-fromfirst-to-final-valentines 2 (accessed January 17, 2025).

24. Ryan Boyle, “The Royal Jesters: From First to Final Valentine’s,” 3.

25. Corpus Gold: Los Dinos - So Hard to Tell (1963) (accessed January 17, 2025).

26. Glynis Ward, “Girl Groups, Part One: The Doowop Era.” https://www.coololdstuff.com/doowop1.html (accessed December 17, 2024).

27. Molina, 37.

28. Joe Nick Patoski, “60 Years Ago, San Antonio Teenagers Invented the Westside Sound,” Texas Observer, December 2020.

29. Molina, 25.

30. For examples of this type of music, see “Finger Poppin’ Time” by Hank Ballard and The Midnighters, “There Is Something on Your Mind” by Big Jay McNeely, or “Pachuko Hop” by Chuck Higgins.

31. Most of these groups were influenced by Spot Barnett, a local San Antonio saxophonist.

32. For pictures of these two groups see Molina, 22 and 24. All the members of these groups were not identitied. According to the pictures guitarist Vic Montes was one of the members of the Exclusives. Hector “Tito” Nievs and Rocky Morales are identified as being members of the Silhouettes.

33. See pictures of the Dell-Kings and the Satin Souls in Molina for an example of the twin saxes used by these groups in the early 60s. Molina, 26-27.

34. Hernández, 52-60.

35. “The story of the Hammond B3, shown by four of its greatest players,” mixdownmag.com.au (accessed June 28, 2024).

36. Molina, 26.

37. For an informative article on the importance of the organ to the Memphis sound see Alex Greene, Rev. Charles E. Hodges — "The Keys to the Memphis Sound,” Memphis Magazine, November 30, 2023 (accessed June 23, 2024).

38. Ray Cano, Jr., “The Legacy of Sunny and the Sunliners: Pioneers of Tejano Music,” tshaonline.org (accessed June 24, 2024).

39. The Official Sunny Ozuna Web Site accessed 08/20/23. (“Talk to Me” made it to number eleven on the national charts, number twenty-four on the R&B charts).

40. His first recording of “Just a Moment” in 1958 had one sax. Molina, 31.

41. Molina, 30-36.

42. Molina, 25-27.

43. Little Joe’s full name is Jose Maria de Leon Hernandez. He was raised in a large poor family of cotton pickers. He initially joined Coronado’s group in 1954. He was sixteen years old then. For additional information on Little Joe see Hernandez, n.d. and Emma Gonzalez, No Llore, Chingón: An American Story-The Life of Little Joe (Edinburg, Tx: Two Cotton Pickers, 2020).

44. Hernández, 53.

45. Molina, 27.

46. For additional information on La Onda Chicana see Manuel Pena, The Mexican American Orquesta, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999), 227-274.

47. Manuel Peña, Música Tejana (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1999), 158.

48. Peña, Música Tejana, 154.

49. Peña, Música Tejana, 158.

50. Emilio Zamora, Andres Tijerina, Guadalupe San Miguel, Sonia Hernández, and Amy Porter, Mexican Americans of Texas: A History of Tradition and Struggle (Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt, 2023), chapters 13-15.

51. Molina, 41.

52. Molina, 42.