Texas Jazz Singer: Louise Tobin in the Golden Age of Swing and Beyond

By Kevin Edward Mooney (College Station, Texas A&M University Press, 2021)

For those readers interested in jazz history, the gaps in the oeuvre are all too familiar and frustrating, especially for the layers of artists outside the big stars who warrant their own in-depth scholarly studies. Too often our biographical exposure to compelling figures from even the recent past, as in the case of swing, are relegated to liner notes, brief mentions in broader studies or compendia, and, of course, the music itself. Thanks to music historian and jazz guitarist Kevin Edward Mooney, we have now bridged at least one longstanding gap in the swing era in a way that preserves unique personal insights and highlights Texas benchmarks in the overall context.

Through the life of Texas chanteuse Louise Tobin, Mooney deftly explores a wide swath of jazz history—from territory bands and the heyday of swing in the 1930s and 1940s to the years of redefined relevance in jazz parties, recording sessions, supper clubs, and rediscovery in the 1960s and 1970s. Along the way he introduces, with great historical respect and admiration, such seminal characters as trumpeters and bandleaders Bobby Hackett and Harry James (Tobin’s first husband, married in 1935), crooner Frank Sinatra, clarinetist and bandleader Benny Goodman, publicist George T. Simon, and many others. Against the surface backdrop of glamour and celebrity, Tobin’s life is revealed in distinct stages of reality as she deals with the seemingly disparate challenges of being a performer (child and adult), orchestra wife, mother, housewife, musical stylist, business partner, and caregiver. Mooney had unprecedented access to the artist, primarily through oral history interviews he and others conducted with her on various occasions and through an extensive archival collection Tobin carefully preserved in association with her second husband, bandleader and club owner Michael Andrew “Peanuts” Hucko. The resulting Louise Tobin and Peanuts Hucko Jazz Collection at Texas A&M University-Commerce is a remarkable assemblage of performance and promotional materials, photographs, and ephemera of two extraordinary artists.

The interviews, especially, provide unique personal perspectives on the swing era, taking the reader far beyond the limits of time and place. Speaking of her love for improvisation, a hallmark of her own styling, Tobin noted, “Blues is the basics; you just write your own story to it however you feel.” With regard to Peanuts Hucko’s Club Navarre, a posh entertainment venue she and her husband managed in Denver during the 1960s, she recalled, “We had the club for three years, and it was great, until a new partner wanted to put rock and roll in one of the downstairs rooms. Peanuts was not interested in that, and we went to California and got a big band.” Her memory back to that event gives insight to something far more universal—the ever-changing continuum of popular music. Swing and supper club jazz were barely hanging on “the scene” at the time, and Tobin was one of the individuals vamping for time and possible rediscovery. That big band music is still a relevant part of jazz today, albeit changed in significant ways, is in part a testament to those like Tobin who kept it vital. She is a survivor, and her story is an important one. Louise Tobin lives where her music is played and appreciated. We are in her debt—and that of her biographer—for bridging the gap.

-Dan Utley

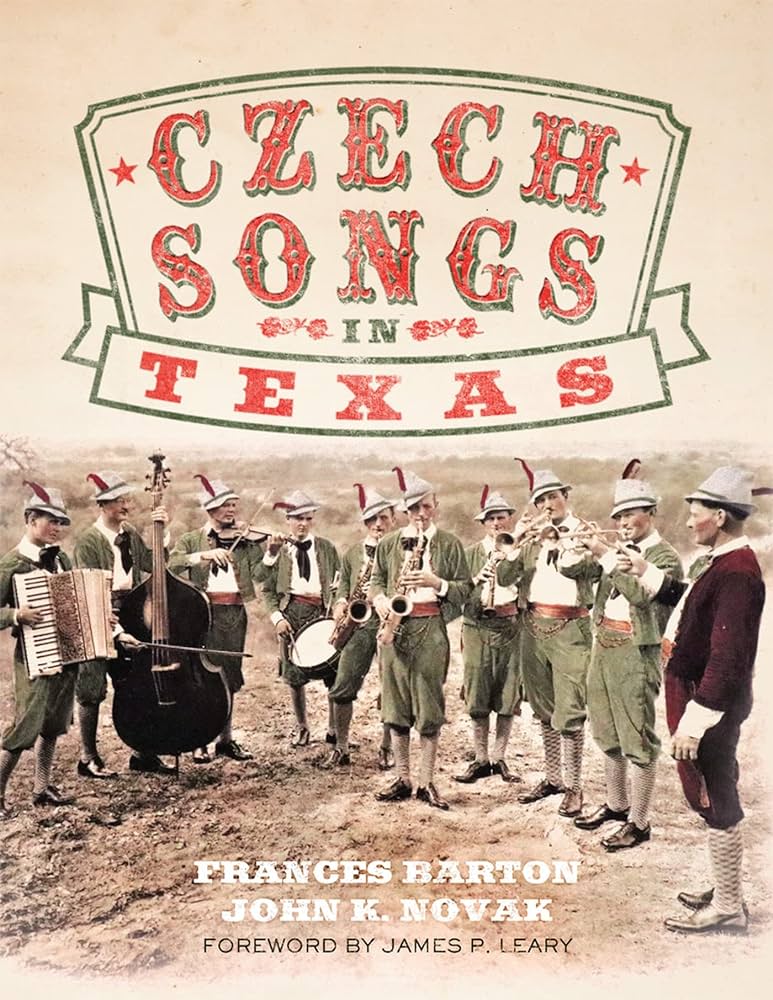

Czech Songs in Texas

By Francis Barton and John K. Novak (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2021)

One of the most interesting aspects of the American Southwest’s musical history is the influence of Czech music throughout the region. Frances Barton and John K. Novak’s Czech Songs in Texas serves as an excellent introduction to this often overlooked aspect of the state’s musical tapestry. Czechs were one of the largest ethnic groups to come to Texas, beginning in the 1840s. By the mid-twentieth century, tens of thousands had settled across the state. Most came seeking new economic opportunities, although many also fled political instability and persecution back in Europe. Ethnic Czechs had lived in the Central European provinces of Bohemia and Moravia since the 5th century A.D., but they had long struggled against domination by their more powerful neighbors, the Germans, Poles, Russians, and Austrians.

Although Germans and Czechs are ethnically and linguistically distinct groups, they had lived alongside each other for years in Europe. Consequently, the earliest Czechs in Texas often settled within already-established German communities. However, as Czechs began arriving in larger numbers by the late 1800s, they founded Fayetteville, La Grange, Praha, and other towns of their own, as well as expanding their presence in such cities as Corpus Christi and San Antonio.

Much like the Germans, Czech immigrants established numerous social organizations to celebrate and preserve their cultural traditions. Nearly every Texas-Czech community had singing societies, church choirs, and local bands, which ranged from guitar-fiddle duos to orchestras. Most Czech musical groups had a broad repertoire, which could include polkas, waltzes, schottisches, and folk songs. Eventually, many Texas-Czech musicians also combined elements of jazz, pop, and country with more traditional Czech music.

One of the best examples of the significance of music in the Texas-Czech histories Barton and Novak document is the proliferation of S.P.J.S.T halls across the state. The S.P.J.S.T. (Slavonic Benevolent Order of the State of Texas) was founded in 1897 as a fraternal organization designed to provide social, cultural, and economic support for Czech immigrants. The S.P.J.S.T. built a statewide network of nearly 200 lodges, which doubled as community centers and dance halls. Although the halls began as gathering places for Czechs, many eventually opened to the public and began featuring music as diverse as country, blues, conjunto, and rock and roll. Today, several S.P.J.S.T. lodges still serve as popular dance halls throughout the state.

Texas Czechs continue to keep their musical traditions alive through Czech-language radio programs, festivals, and other events. In addition, the Texas Czech Heritage and Cultural Center in La Grange and other organizations offer a variety of activities aimed at preserving and promoting Czech culture.

Although Texas-Czech music remains one of the least-understood genres in the Southwest, Czech Songs in Texas should help remedy this. Barton and Novak have spent decades studying Czech music in Texas, not only by mining the existing scholarship on the topic, but also by experiencing it directly through spending time in the still vibrant Czech communities around the state.

The first part of this book includes a brief but nicely detailed history of ethnic Czechs in Texas. The authors draw from an extensive list of books, articles, recordings, and interviews in order to cover nearly every aspect of Texas-Czech history, culture, and music. They augment this with personal anecdotes taken from years of first-hand involvement in the Czech community.

Finally, Barton and Novak examine 61 Czech songs performed by bands around the state. For each song, the authors provide the original Czech lyrics, an English translation, and a brief discussion of the song’s significance as it relates to Texas-Czech musicians and their audiences. Added to this are a dozen vintage photographs, which help make this book a comprehensive source of information on Texas-Czech history, culture, and music. Written in a highly accessible and engaging style, Czech Songs in Texas may well be the most informative and entertaining book yet on this topic.

-Gary Hartman

DJ Screw: A Life in Slow Revolution

By Lance Scott Walker (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2022)

The product of interviews with more than 150 people since 2005, A Life in Slow Revolution melds Lance Scott Walker’s massive oral history project and incisive prose to tell the story of Robert Earl Davis, Jr., the Houston DJ, producer, rap ringleader, and sonic innovator known as DJ Screw. Screw’s popularity emerged from his enormous output of masterfully and mysteriously crafted mixtapes known as Screw tapes—slowed-down versions of what he and the rappers were producing in real time in the studio. The members of the Screwed Up Click, the ever-shifting collective of South Houston rappers who worked with Screw, are given their due. It is a story of Houston hip-hop and a survey of life in the sprawling, foreboding metropolis. One wonders if such an in-depth report on music and culture from outside “the loop” in Houston has been committed to the page. “Chopped and screwed” was the sound, and DJ Screw was the architect of these psychedelic, tempo-altered mix tapes and productions.

The depth of Walker’s oral history work is boldly evidenced in Houston Rap Tapes: An Oral History of Bayou City Hip-Hop, his collaboration with photographer Pete Beste. But readers who thought all stones had been overturned will be astonished to find his project barrels forth in A Life in Slow Revolution with a seemingly endless well of interview excerpts. While Houston Rap Tapes relies primarily on lengthy interview excerpts, Beste’s photography, and brief but informative introductory passages from Walker, A Life in Slow Revolution affords Walker much more space to craft an authoritative critical history of the music and a biography of one of its most important figures. The wealth of details, anecdotes, and indispensable historical notes in A Life in Slow Revolution make it an essential volume for Screw and third-coast rap fans and Houston music history scholars.

Walker explains how Screw’s story begins not in South Houston but in the small Central Texas town of Smithville, his birthplace an hour east of Austin on the Colorado River. Austin, too, serves as a significant site in Screw’s story, for it was KAZI, the city’s Black community radio station, that gave Screw some of his first tastes of the burgeoning rap genre as their broadcasts intermittently reached Smithville.

Of course, DJ Screw was not the first producer to significantly slow down the sound of their finished product. With a fondness for supernaturally slow tempos, Jamaican and British dub producers like Lee “Scratch” Perry and Dennis “Blackbeard” Bovell have pursued groundbreaking production practices since the 1970s. Walker comments on the recent compilation from the Analog Africa label entitled Saturno 2000: Le Rebajada de Los Sonideros 1962-1983, which chronicles the pitch-shifted and slowed sounds of South and Central American and Mexican cumbia. He details the history of early audio sludge-making by revolutionary Houstonites Lester “Sir” Pace and Darryl Scott and connects the dots that lead to Screw’s chopped and screwed production work.

Walker also meditates on the life, music, and legacy of Screwed Up Click rapper Big Floyd, aka George Floyd, a former Yates High School student whose murder by a Minneapolis police officer in 2020 set off protests across the country. Floyd’s Cuney Homes friend Cal Wayne succinctly notes, “All the stuff they were doin’, marching, protesting, he deserved it. He deserved all the support. He deserved it to be worldwide.” Big Floyd, along with far too many other Houston rappers and producers who have passed, are never left behind in A Life. Walker details their contributions to the music, their relationships with DJ Screw, and their inspiring legacies.

Accounts of Screw’s untimely passing and the grief that overwhelmed his family and the rap scene leave no doubt as to his profound impact. Interviews with Screw’s closest relations, such as Screw’s sister, Michelle “Red” Weaver; Al-D, South Park rapper and close friend of Screw’s from high school; and Screw’s partner, Nikki Williams, exemplify the depth of his relationships and the influence he had on his city and his people.

While the tales of life in the studio, in the club, and behind the wheel are central to the book, what dominates the story of DJ Screw is his desire to help his family, his friends, and his colleagues in the rap game. Walker quotes Screw from an interview with Daika Bray: “I live and die for this shit, every day. I’ll do the best I can, try to keep my name up high. For my family, for the ones that’s with us, upcoming generations. The young BGs, they see us rappin’, they really like that. I’m tryna pave the way so they can shine, too.” When DJ Screw announced he wanted to “Screw the world,” it was a proclamation only he could own but one that was as much about his own revolutionary approaches to DJing as it was about empowering both his own family and his Houston rap family.

- Alan Schaefer

Horse Racing and Rock 'N' Roll: How America's Live Music Capital Tripped Out, Cowboyed Up, and Shook the World

By Woody Roberts (Austin: Press 709, 2019)

In his memoir Horse Racing and Rock ’N’ Roll, Woody Roberts gives readers a privileged “backstage pass” to the emergence of Austin, Texas, as a cultural and musical hub. The book covers the better part of the last fifty years of Central Texas music history, including his prominent roles in San Antonio radio, the Armadillo World Headquarters, and the Austin racetrack and concert space at Manor Downs. The account begins around the early days of Willie Nelson’s first Fourth of July picnic, takes the reader through the nineties and the emergence of alt-rock, and even involves contemporary figures such as blues-rocker Gary Clark, Jr.

Upon first reading, one might discover that this book works as one of the better musical encyclopedias in recent memory. One read through is enough to stuff one’s music library full of names like Greezy Wheels, Commander Cody & the Lost Planet Airmen, and Freddie King (and that’s only when you aren’t being blow away by the abundance of household names who made their way through Austin and San Antonio during the time period: Led Zeppelin, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, Bruce Springsteen, and David Bowie to name a few). However, what makes this particular memoir so compelling is that it traverses so far beyond music into show production and promotion that the reader can feel as if he or she has just assisted in pulling off a South by Southwest show or Austin City Limits episode or cut a hip advertising spot for Lone Star Beer.

That this book moves at such a breakneck pace will undoubtedly lead to some criticisms—Roberts manages to somehow churn out around eighty-eight chapters in a little over three hundred pages—yet, Roberts tells the story with pace and concision. The end result feels like a Ramones album: short, sweet, fast, and fun. Part one gives an overview of Willie Nelson’s rise from aspiring Nashville songster to celebrated Austin staple. Part two elegantly describes Austin’s nightclub scene across the decades, describing everything from the psychedelic sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators and Shiva’s Headband at the Vulcan Gas Company to Sixth Street blues venues like Antone’s, Parts three and four round out the ride with everything from Austin filmmaking to digital arts before bringing the book to its crescendo with a fascinating description of the ups and downs of the Manor Downs horse track, a venue Roberts managed that hosted memorable concerts by the Grateful Dead and the Rolling Stones and played a role in Stevie Ray Vaughan’s rise to stardom.

Though Texas music and history aficionados will see many familiar faces and places here (the author’s working relationship with Eddie Wilson and the Armadillo World Headquarters comes to mind), Roberts provides a valuable and distinct contribution to the growing body of literature on Austin music, art, and popular culture. He pays close attention to the business and venue side of things without losing sight of audience-pleasing artist biographies. Thanks to Roberts, there has arguably never been a cooler time to be a hippie cowboy with a backstage pass to Austin history.

- Kevin Mitchell