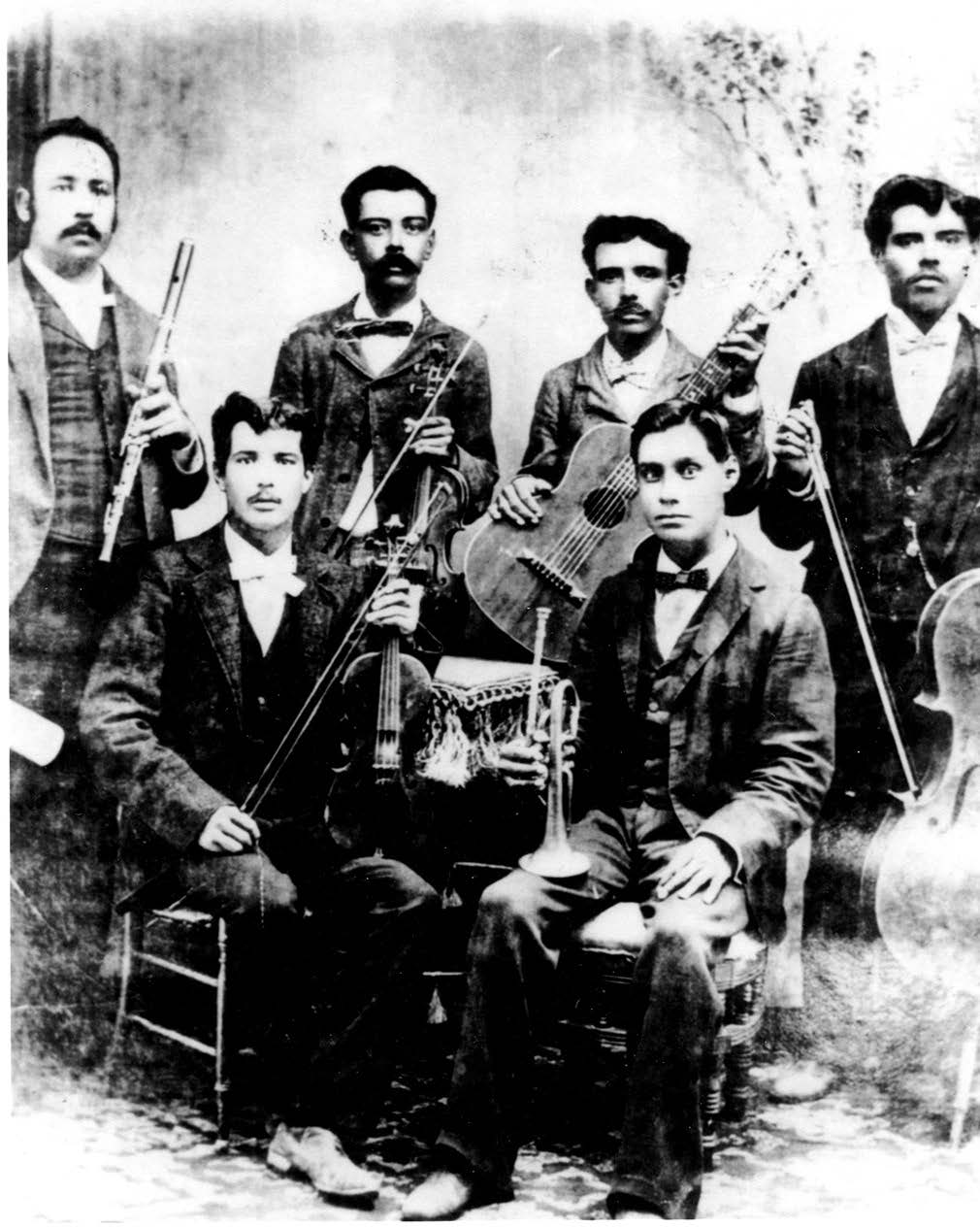

The Perez Family Orchestra: Three Generations of Family Music 1893-1950s

Marguerite Gutierrez Hirsch

Mary Perez Carbajal, 1940.

From the Author's Collection.

My mother, Juanita Concepción Perez Gutierrez, spoke fondly of her grandfather, musician Encarnación Perez. Encarnación was born at the Presidio La Bahía to Juan Jose Perez and Ana Maria Flores in about 1825. Juan Jose Perez was also born in La Bahía in about 1795. The Perezes of South Texas have a long history, as does La Bahía.

La Bahía

The Marquis de Aguayo founded La Bahía in 1722 on Garcitas Creek, which is in present day northeastern Victoria County at the Jackson County line. This location failed, and La Bahía was moved to a second site on the Guadalupe River. It was successful and remained there for twenty-six years. Today this area is known as Mission Valley and is in the eastern part of Victoria County. Presidio La Bahía was again moved with its chapel furnishings in 1749 to its present location in Goliad. It was believed that this location was better situated for a fort, which guarded the main road between Mexico, San Antonio, and East Texas. Presidio La Bahía had always been a primary military post in Texas even though San Antonio had always been given more attention. The chapel, known as Our Lady of Loreto for the statue that moved with the fort, also plays a role in the history of the Perez Orchestra.1

Encarnación and the Founding of the Orquesta

Encarnación played several instruments and was said to be an exceptionally talented musician. He could play the piano, violin, flute, cello, and guitar. It was said that he was such a talented violinist, he could swim on his back across the Rio Grande while playing the violin. Encarnación had three siblings: Jesus, born about 1812; Refugio, born about 1814; and Maria Carmel, born about 1819. Encarnación married Maria Ignacia Garcia, his first wife, on June 29th, 1847, in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico. They had three children: Romaldo, born about 1848; Juana, born about 1849; and Benita, born about 1852. Maria appears to have died around this time. Marriage records show he was the widower of Maria when he married his second wife, Francisca Gonzales, sometime between 1852 and 1865. Francisca had two boys: Juan, born about 1866, and Alberto, born about 1868. Francisca probably died in childbirth, and Encarnación was again left a widower with five children to raise. He met Pomposa Garcia, soon to be his third and last wife. He was forty-four years old, and she was twenty. His children ranged in ages from one to 21. Pomposa and Encarnación married on December 9, 1869, at the Immaculate Conception church in Brownsville, Texas. It appears that Encarnación stayed in the Brownsville area until after 1880 and then moved to Goliad, where he and Pomposa lived with their family of five boys and two girls.

From the Author's

Collection.

By the time Encarnación was 68, he had taught his children to play the various musical instruments that he could play, and he was determined to start a family orchestra along with two friends. Thus, the Perez Family Orchestra was born in 1893. The band was comprised of the four brothers— Hipolito, Esteban, Domingo, and Pedro—and Encarnación. Additionally, Blas Falcon and Facundo Caceres, two family friends, were also members of the band. Twenty-three-year- old Hipolito played the violin, guitar, and flute. In addition to the band, Hipolito also played with a group of three women in the town of Charco.2 This group provided entertainment for the people of the town on occasion, and Hipolito was found to be a great help and inspiration. Eighteen-year-old Esteban played the violin. Domingo was sixteen and played the guitar and cello. Pedro, thirteen, played guitar and the flute. Family friends Blas Falcon played the flute and Facundo Caceres played the trumpet. Before Encarnación died in 1898, he had made his sons promise to continue to play as an orquesta. The orquesta became known as the Perez String Band or La Bahía String Band. They played at private homes, races, dance halls, auditoriums, weddings, and baseball games. They even played funerals and barbecues.

Orquestas Típicas

Encarnación’s orquesta was one that likely developed because of his exposure to orquestas típicas in Mexico and Brownsville. An orquesta típica in Mexico in the nineteenth century consisted of five to seven instruments centered around the violin.3 In addition to the violins were a bajo sexto (twelve-string guitar), a mandolin, and a contrabass, with flute or coronet and a psaltery. As Manuel Peña argues in The Mexican American Orquesta, orquestas típicas may have evolved from groups that were better organized such as those that performed zarzuelas or tonadillas (Spanish musical comedy) and follas (poetry readings with music). Of course, the incarnation of the orquesta típica among the less affluent peoples of the countryside depended upon musical instruments available, and therefore the sound was likely less complex in its presentation.4 The mariachi band is thought to have evolved from the orquesta típica. In the early 1800’s orquestas típicas were associated with working-class musical groups. However, by the late nineteenth century they had been appropriated by the middle class, and support for the típicas grew smaller and smaller.5

Some of the larger Texas cities such as Brownsville, San Antonio, and Laredo also had orquestas típicas. In Brownsville, one of the most popular musical groups during the late nineteenth century was the Mexican Brass Band. San Antonio had the Mexican Social Club, which sponsored an annual ball during the 1880s and 1890s. Orquestas de cuerdas were generally much smaller than a típica and were composed mostly of violins and guitars of various sizes. Historically there were at least two specific musical groups that were present in the Tejano community. The jarocho group featured a harp and other stringed instruments and originated in the nineteenth century. The other type of group, known as mariachi, was usually composed of stringed instruments such as the Hawaiian guitar, mandolins, and violins; trumpets were not added until the 1920s. The mariachi originated with the French occupation of Mexico in the 1860s. Mariachi is derived from the French word for marriage. The mariachi musicians were asked to play for many of the French festivities, especially weddings. Thus, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, mariachi referred to any musical group performing at a wedding.

A third type of orquesta was known as orquesta de pitos, which was composed of wind instruments such as French horns, clarinets, flutes, saxophones, tubas, trombones, and trumpets. This type of orquesta was common for ceremonial occasions and popular with the supporters of Porfirio Díaz. The most popular of this type of music in the late nineteenth century was the Eighth Cavalry Mexican Band. South Texas also saw bandas, groups that featured primarily brass and percussion, appear in the late nineteenth century. Brass bands were quite popular in South Texas; Brownsville became the home of the Mexican Brass Band. Of these three types of orquestas, only the típicas and orquestas de cuerdas played for dances. I argue that Encarnación based his orquesta on the típica since there were only six people and they played two violins, guitar, cello, flute, and cornet.6

Perez Dance Hall

The property where my grandmother’s house stood on the west bank of the San Antonio River, on a bluff across the highway from La Bahía, was deeded to Hipolito Perez Sr. in August of 1898 from Tomas de la Garza, his brother-in-law, for the sum of $30. My mother believed that this property had been given to Hipolito in payment for playing music at a function for the de la Garzas. It was also about this time that a dance hall may have been erected next door to my grandmother’s house. I remember seeing such a structure as a child in the mid 1940s. My mother spoke of the many dances held there and of her uncles preparing tamales to sell at the dances. Having their own dance hall was invaluable in providing music and entertainment, plus it offered a meeting place for community activities for their families, friends, and neighbors.

The Founding of Refugio and Irish Empresarios

The Perez orquesta often played in Refugio in its early days. Refugio was a pretty lonely site at the time. The mission Nuestra Señora del Refugio was moved to its present site in the town of Refugio in 1795. It operated continuously until February of 1830 and was the last mission to be secularized when the area was still part of Mexico. By this time, a village existed around the mission and there were at least 100 Mexicans living in ranchos nearby.

Two Irishmen, James Power and James Hewetson, one who was living in Mexico and the other still in Ireland, applied for and received an empresario contract to colonize the Texas coast with Irish Catholic and Mexican families. They took advantage of the Mexican colonization law of March 24, 1825. The lands extended from the Nueces to the Sabine but were later modified on June 11, 1828, when the national government and the state of Coahuila granted them ten littoral leagues lying between the Lavaca and Guadalupe rivers. The Irishmen asked for more land, and on April 12, 1829, the territory was extended from the Guadalupe to the Nueces rivers. Power and Hewetson now had control of the old mission building and the town that surrounded it. There were boundary disputes between 1829 and 1831 with the other empresarios in the area, such as Martín De León (founder of Victoria, Texas) and John McMullen and James McGloin, who were founders of San Patricio de Hibernia (St. Patrick of Ireland) on the east bank of the Nueces. The boundary disputes with De León were finally settled when Power and Hewetson accepted the littoral lands lying between Coleto Creek and the mouth of the Nueces River. In 1834 the villa became the center of the Refugio municipality. James Power’s grandson, Thomas O’Connor III, married Kathryn Stoner. Kathryn Stoner O’Connor was the author of the book The Presidio La Bahía del Espíritu Santo de Zúñiga 1721 to 1846. She was also best known for her work in restoring and preserving La Bahía in the 1960s.7

Refugio Under Siege

On March 14, 1836, General José Urrea, under the direction of Santa Ana, overran the town of Refugio and San Patricio, scattering its residents, who fled to Victoria, Goliad, and other areas. My mother’s maternal ancestors were driven from this area to Goliad. Some Irish residents deserted the American Army and went to Mexico to fight on the side of justice as they saw it. They fought four battles before being decimated. An album called San Patricio by the Chieftains featuring Ry Cooder recounts this story in song.

Between the Texas-Mexican war for independence in 1836 and the Civil War in 1860, Refugio suffered immensely. People moved away and did not return for a long time. Twice it was without government; gambling houses and saloons proliferated during the 1860s and 1870s. The county seat was moved from Refugio to St. Mary’s and then to Rockport. By 1871, Aransas County had been formed from part of Refugio County and the government of Refugio County was returned to the town of Refugio. The town finally began to revive and by 1884 included a wooden courthouse (a future venue of the Perez Orquesta). It also included two churches and two public schools, one for Black students and one for white students.

Perez Orquesta and the Christmas Dances

The Old Hipolito Perez Orquesta played for most of the Christmas dances in Refugio. He was referred to as old Hipolito, as he had a son by the same name, Hipolito Jr., who was in the band.8 He and his music were an institution in Refugio and the surrounding communities.

The Christmas dance was a major community affair in late-nineteenth-century Refugio. It was usually held in the courtroom of the old courthouse on the night of December 26th. There were several different musical organizations that played for the dances. Hipolito Perez played for many of them as he was well liked. Another desirable band was the Brightman Boys of Old St. Mary’s. The Brightmans also played violins and guitars.

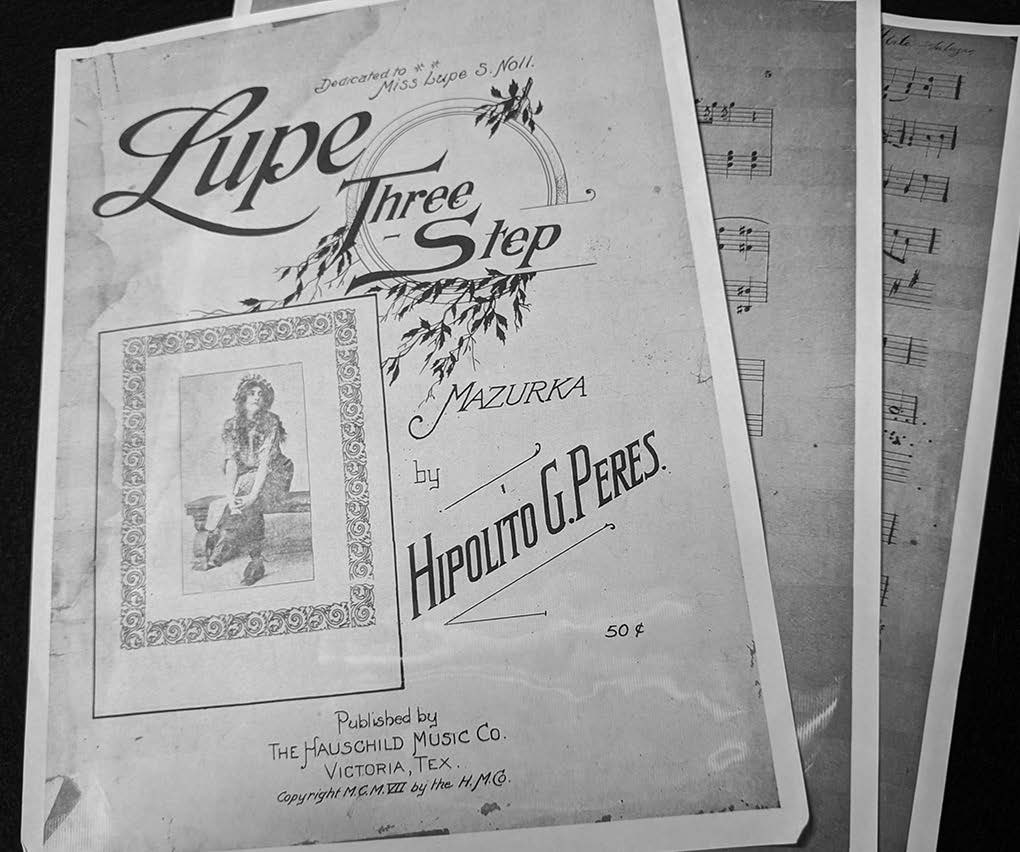

"Lupe Three Step" with

Hauschild Music Company, 1907.

From the Author's Collection.

Christmas and the Fourth of July were annual and well attended celebrations in Refugio. The people from Goliad, Beeville, and Victoria often came for the festivities. Pony or quarter horse races were held during Christmas week and a dance was held each evening right after the races, except for Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. Going to Midnight Mass or other church services was a significant activity for the people. The races, dances, and church activities were the principal celebratory pursuits in those horse and buggy days. After the dances, the young men would take the musicians around town to serenade their sweethearts and their friends.

Old Hipolito brought his band from Goliad and played the dances. This was probably a difficult journey in a horse and buggy, but his band was the leading band of the time period. Hipolito Jr. was the leader of the band and the grandson of Encarnación. Beginning in 1918, the big Christmas dances were held in the new auditorium in Refugio. Although the popularity of Hipolito’s band was beginning to wane among the younger generation, the older generation was still fond of his music.

The senior Hipolito, who had listed himself as a musician in the previous two censuses, began to list himself as a music teacher in the 1920 census.9 He lived in town and was probably not only teaching the children of the community but also his own children and perhaps his nieces and nephews, who would become future members of the band. Hipolito composed and had published some music through the Hauschild Opera and Music Publishing House of Victoria, Texas. The piece he composed was entitled “Lupe Three Step,” which was a mazurka, a type of waltz.10 Blas Falcon, a band member, had also composed and published a piece with Hauschild, title unknown.

Hauschild Opera House

George Hermann Hauschild built the Opera House in 1891 in Victoria. It was one of the largest publishers of sheet music in the Southwest between the years of 1891 to 1922. It was one of two early music publishers in Texas and was the first to publish Texas-Mexican composers. They were among his top hits and best sellers, and a special price list for what the company called its “Popular Mexican Music’’ series was offered to the public. The Tejano compositions consisted mainly of waltzes and polkas. Among the seven Tejano composers, one was a woman, Leonora Rivas Diaz. Hauschild Music Company published the following Texas-Mexican composers, including two members of the Perez Orquesta: A.M. Alvarado, Leonardo F. Balado, Blas Falcon, Juan R. Guerra, Abundio Martinez, Hipolito Perez, and Leonora Rivas Diaz. In all there were about forty works by Texas-Mexican composers that were published by Hauschild Music Company. By recognizing and opening its publishing venue to Tejanos and women, the company established an important precedent.11

Pedro, Hipolito’s brother, also composed two pieces, neither of which he published. They were entitled “Tus Caricias” (“Your Caresses”) and “Estefanita” (“Stephanie”). Both were waltzes. I interviewed Mary Perez Carbajal, the daughter of Pedro Perez, who was both a singer and bass player with the band. She told me that popular music of the day included such pieces as “La Golondrina,” “Estrellita,” “Quiereme Mucho,” and “La Paloma,” which were played by the band. These four pieces were all written between 1850 and 1912.

Lydia Mendoza and the Texas Triangle

Women in Hispanic culture in this era were quite limited in their career choices. They were expected to marry, stay home, and take care of the children. They were not expected to be singers or performers of any kind, nor to compose music. Lydia Mendoza, a popular singer of this era, was from Houston and was the exception. She was the first female star of recorded Tejano music. She recorded with her parents and her sister in San Antonio in 1928. They were living in Kingsville at the time. Her father, Francisco Mendoza, after seeing an advertisement in the Spanish language newspaper La Prensa about a recording opportunity in San Antonio, decided the family should leave at once. Of course, they had a car, but it was an old one. They hurriedly gathered their things and got in the car for the 150- mile trip. After two days and twenty flats, they finally arrived. The Mendoza family group, called the Cuarteto Carta Blanca, recorded twenty-eight songs for the Okeh record label. It seems their enthusiasm to endure such a troublesome journey was key to her successful career.12 She traveled throughout what Mary Ann Villareal has dubbed the South Texas Triangle of Corpus Christi, San Antonio, and Houston, as well as other parts of the United States and Latin America. Her choice of canciónes rancheras in her repertoire appealed to a wide audience of Mexican Americans and more recent immigrants.13 Villareal describes the South Texas Triangle as an area that saw the development of women entrepreneurs, family-owned businesses, and business communities. The Triangle area offered numerous opportunities to provide entertainment for the populations in both rural and urban centers as well as the many migrant workers.

The South Texas the Perez Orquesta called home has a tumultuous history of segregation and racial discrimination. Signs saying “No Mexicans or dogs allowed” proliferated throughout the region. Schools for Mexican children began in the town of Seguin in 1902, and by the 1930s almost all schools in South Texas were segregated. This did not happen in some parts of the South Texas Triangle such as Houston, where the Mexican population was small at the time the Jim Crow laws were written. Mexicans were legally white. This allowed Mexicans to sit where they wanted on a trolley or bus, whereas the Black people were made to sit in the back. Migration to Houston by the ethnic Mexicans was motivated by the civil war in Mexico that began in 1910. There was a settlement near the ship channel called Magnolia Park that was made up of ethnic Mexicans. There were pockets of ethnic Mexicans throughout the city. Other small groups settled in what was called Second Ward or Segundo Barrio, an area called Denver Harbor where I grew up, and a small settlement on the west side of the city called Sixth Ward. Language was divisive among the ethnic Mexicans and the Texas-born Mexicans or Tejanos. Ethnic Mexicans often spoke different dialects of Spanish or rapid Spanish, while Tejanos often altered the language, using loan words such as el troque for truck instead of the traditional word, el camión. Cultural practices often caused differences with respect to musical styles. Frank Alonzo, a San Antonian whose family group was known as Alonzo y Su Orquesta, did not like the many musical styles from Mexico. Musical styles from Texas included the corrido, a narrative ballad, and conjunto, which included an accordion in the instrumentation. Ethnic Mexicans seemed to prefer bolero, a guitar-based style, and canción ranchera, similar to American country and western music, which would have appealed to those Mexicans from rural areas of Mexico. Frank and his wife Ventura, a piano accordionist, were very popular in the Houston area. She became known as the Queen of the Accordion, as she was the first Hispanic woman accordionist. Their dance hall, La Terraza, located in Magnolia Park, was quite successful for fifteen years.14

Perez Orquesta and the Choir of Our Lady of Loreto

The choir of the chapel of Our Lady of Loreto as well as the Perez band took part in the annual festivities at La Bahía. One of those festivities was the feast day of San Isidro, the patron saint of farmers. This feast day occurs on May 15, and the people pray for a good harvest during the Mass. Encarnación’s daughters, Isabel and Julia, were both members of the choir, and Isabel was the last Perez to serve as the choir director. The choir members, all dressed in white, made quite an impressive display. There were many activities, including a barbecue, pony races, and a beauty pageant. One year, Ignacia Perez Martinez was chosen queen. Another year Anita Perez Salazar was chosen queen. Both of these young ladies were the granddaughters of Encarnación Perez. Following all these activities was the dance in the Perez dance hall, the culmination of a very full and enjoyable day.

By 1920, two of the band members had moved away from Goliad but continued to return to play at their dance hall and in the Victoria area. According to the Victoria Advocate, on November 19, 1908, La Bahía Band played at the Hauschild Opera House for the annual ball given by the Iroquois Club. Another notice in that newspaper stated that La Bahía String Band provided the music for a social event sponsored by the B.P.O. Elks. During this time, Hipolito Jr. led the band. Each of the band members had married and had growing families. Some of the children were learning to play the various instruments and to sing and would become future members of the band.

Victoria and De León’s Colony

As previously mentioned, La Bahía string band often played in Victoria in local venues such as the Elks Club and the Hauschild Opera House. Victoria was founded in 1824 by Martín De León. It was the only predominantly Mexican colony in empresario-era Texas north of the Nueces, which then marked the province’s boundary with Tamaulipas. He applied to the provincial delegation of San Fernando de Bexar for permission to settle forty-one residents and founded the town of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Jesús Victoria. Guadalupe Victoria was a hero of the Mexican War for Independence from Spain in 1821 and became the first president of the new republic of Mexico. After the town was platted, De León designated the main street Calle de los Diez Amigos, signifying unity among ten friends. Martín De León was the first Alcalde of Guadalupe Victoria and was the first of the ten friends; others included his three sons-in-law, J.M.J. Carbajal; Plácido Benavides, a militia captain; and Rafael Manchola, who was an attorney and a commandant of La Bahía. Silvestre and Fernando, De León’s sons, were also counted among the ten friends. Today in Victoria the main plaza is called Plaza de los Diez Amigos. De León was able to satisfy his empresario contract within two years of starting his colony. But they were not all Mexicans. Among the settlers were John Linn, John D. Wright, and Joseph Ware. It was De León’s openness in accepting anyone who was interested in settling in Guadalupe Victoria that allowed him to complete his contract. In fact, he was able to settle more than one hundred families, many from Tamaulipas and a few from the United States. The De León family were ardent Federalists and supported the revolution against Santa Anna, as were many citizens of Guadalupe Victoria. Some of those citizens included John Linn, Juan Antonio Padilla, Jose J.M. Carbajal, Placido Benavides, and Fernando De León. Santa Ana considered them traitors since most were of Spanish descent and were made to suffer severely. They suffered again after the battle of San Jacinto because the Anglo Americans, many of whom were fortune hunters and soldiers, branded them Mexican sympathizers. The De León family was particularly ostracized and forced to flee to Louisiana and Mexico. They lost much of their land, and it wasn’t until 1850, through many court battles and lawsuits, that they were able to regain their property. Other Mexican families were not as fortunate, but many of the descendants of the original Mexican families still live in Victoria today, some on their ancestral lands. After the immigration of new settlers—Germans, Italians, Irish, and Jews—Guadalupe Victoria became an English-speaking colony, and the name Guadalupe was dropped and simply became Victoria. 15 16 The Perez Orquesta often played in Victoria, but the town was not known for its inclusiveness of Mexican Americans. And although they played in certain venues in the town, there were no dance halls that were inclusive of Mexicans. Dance halls were not inclusive in Victoria until the 1960s, and then they were located on the outskirts of town.17 Balde Gonzales was a blind singer/pianist from the Victoria area and a major contributor to the non-ranchera side of orquesta. Gonzales was well known for his smooth baritone voice, and he composed many of his most popular boleros.18

Beto Villa, considered the father of the modern orquesta, was born in Falfurrias, Texas, to an affluent family. His father was a successful tailor and a musician. Villa learned to play the saxophone at an early age and played with the high school band. While still in high school he started his own band with fellow students, which he called the Sonny Boys. They only played American big band songs. By the mid 1940s he decided to change his style of music by including an accordion in addition to saxophone and trumpet. He wanted to play música ranchera with his new instrumentation. He created a unique sound which San Miguel calls lo moderno.19 Villa’s popularity led others to imitate his sound, including Balde Gonzales and Eugenio Gutierrez. By 1949 he again changed his sound, this time by expanding his band from eight to eleven members, and he dismissed the musicians who could not read music. He also removed the accordion. He probably did this because he wanted to create the sound of the big bands he admired that were popular at the time, such as the bands of Tommy Dorsey, Xavier Cugat, and Glenn Miller.

The Perez Orquesta never had an accordion as part of its instrumentation and would not be considered a conjunto-style orquesta. They did not seem to modernize in the Beto Villa mold and continued to play the ballads their audiences loved.

Pedro and the Transition of the Perez Orquesta

Pedro came to my Grandmother, Avelina Perez (Domingo’s widow), to ask that her son Louis be allowed to come and stay with him to help him at his home. Pedro lived in Wharton County. This was told to me by my mother. She didn’t know what he meant by help; she didn’t remember the time period well, but she thought her brother was sixteen. That would have been around 1923. Looking at census records and other genealogical information, I believe Pedro wanted to teach him to play the guitar so that he could participate in the band. There were only two brothers left, Pedro and Steve (Esteban). Both these brothers lived away from Goliad but came back frequently to continue the tradition of the Perez Orquesta. The members included Pedro; his 18-year-old son Mingo; Steve; Louis, Domingo’s son; and Mary, Pedro’s daughter, who was 15. There is a picture of this group that was taken in 1939 in the Perez Dance Hall.20 Pedro’s two children Mingo and Mary were also singers and sang with the band as a duet and as a trio with their cousin Benny Zapata during the early 1940s. Benny was the son of Elvira Perez Zapata. After Pedro’s death in November of 1940, his son Mingo took over the task of leading the band until he was drafted into the military in 1942. There is a photo of the mixed generations, showing Daniel, who was Hipolito Sr.’s son; Benny; Mingo; Esteban; Mary; and Louis, my uncle. This photo was probably also taken in the dance hall before 1942. Mingo served his country and died in Italy in October 1944.

One significant change that did come was the rare inclusion of a woman as a musician in the orquesta when Pedro’s daughter Mary began playing the bass with the band at the age of fourteen. This was reminiscent of her dad, who began playing with the original band at the age of thirteen. Mary said they would tie the bass to the top of the car and go driving down the highway to reach their next destination. She said it was difficult to carry such a large instrument up the stairs of the auditorium in Refugio when they had to play there. According to Encarnación’s two granddaughters, Mary Carbajal and Ignacia Martinez, Mary continued to sing with the orchestra until 1946, and Ignacia said she sang with the band until 1954.

Why Didn’t the Perez Orquesta Change?

As mentioned before, the type of music played by La Bahía band were waltzes and Polish mazurkas. The instruments included strings and woodwinds. And of course, it was an acoustic band, as amplification was still in the future. The band did not seem to be influenced by the jazz and blues sounds of the twenties and thirties. Nor were they swayed by the accordions of the conjunto bands that became popular around the same time. The band kept to its roots, singing the popular Spanish ballads of the day, Mary Carbajal told me. They played songs like “Estrellita,” “Cuando se Quiere de Veras,” “Adios Mariquita Linda,” “La Golondrina,” and “La Barca de Oro”.

Theories about why the group remained fixed to its stylistic roots leads one to question whether the musicians were familiar with certain contemporary sounds. In the 1930 census, a question was asked about who had a radio set. This was a new technology for the time. Hipolito Jr. answered no. He also did not list himself as a musician, but as a barber. He owned a barbershop in Beeville. Musicians from rural areas did not earn enough from their performances to support themselves and their families. One of the most popular conjunto musicians from that era, Narciso Martínez, worked in the fields during the week and performed on the weekend.21 Esteban also listed himself as a barber in the 1930 census. He apparently played with the band and is pictured with some of the remaining members in the photo inside the dance hall in 1939. The other possibility and most likely reason might have been the deaths of Pedro in 1940 followed by the death of Pedro’s son Mingo in 1944. Surely these events had a profound effect on the survivors, especially Mary, who was very close to her brother and her father.

The younger Hipolito’s father died in 1928, bringing his own mortality to the forefront. He had supported his father throughout the height of the band’s popularity, playing and leading the band. Steve (Esteban) began to use the English version of his name after he left Goliad and lived in Fort Bend County. Steve’s oldest son, named for his grandfather, Encarnación, changed his name to John to sound more Anglo. The death of Hipolito Sr. must have influenced the group, but they carried on under the leadership of Pedro and the various other band members, including those in the next generation. Their desire to continue to play was remarkable. With just two brothers remaining and possibly Blas Falcon, the band members were shrinking in number. They needed to rely on the new generation—Pedro’s, Hipolito’s, and Domingo’s children.

The Perez Orquesta’s tenure thus spans much of modern Texas history. In recognition of this fact, in April 2008, Hipolito Sr.’s violin and flute were presented to the University of Houston-Victoria Archive. Included in the presentation was the guitar played by Encarnacion’s grandson, Louis Perez. Mary Carbajal and her sister Ignacia Martinez were both there for the presentation and performed some songs. Henry Wolff Jr., a long-time journalist from the Victoria Advocate, was present at this function and interviewed the two sisters for an article about the occasion. Although I was not able to verify the following, Wolff mentioned that the orquesta played for First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt; however, she did visit Goliad in 1940 to view the historical reconstruction work done by the Civilian Conservation Corps on La Bahía.22 He went on to say the orquesta also played for Al McFadden, a prominent rancher, at his wedding in 1903. In this same article, Wolff quotes Henry J. Hauschild, Victoria historian, as saying, “The Perez Orchestra was ‘Número Uno Por Muchos Años,’” and, given the long generational arc of their time together and indelible presence in the Coastal Bend, it is hard to dispute the contention.23

Notes

- Kathryn Stoner O’Connor, The Presidio La Bahía del Espiritu Santo de Zúñiga, 1721 to 1846 (Austin: Von Boeckmann-Jones, 1966), 34-35.

- Jakie L. Pruett and Everett B. Cole, The History and Heritage of Goliad County (Austin: Eakin Publications, 1983), 53. Researched by the Goliad County Historical Commission.

- Manuel Peña, The Mexican American Orquesta (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999), 80.

- Ibid., 80.

- Guadalupe San Miguel, Jr., Tejano Proud: Tex-Mex Music in the Twentieth Century (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 27-29.

- Ibid., 27-29.

- Thomas O’Connor Papers, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin, accessed March 21, 2021.

- Hobart Huson, “Christmases Past Are Jewels of Recollection in the Casket of Memory,” The Timely Remarks (Refugio, TX), December 22, 1939.

- 1920 Census, Census Place: Goliad,Texas, Roll: T625_1807, Page: 10B, Enumeration District: 73.

- Felicia Piscitelli, “Texas: Where Americans, Mexicans, Germans, and Italians Meet: The Hauschild Music Collection at the Cushing Memorial Library and Archives,” Fontes Artis Musicae 64, no. 3 (July- September 2017): 261–275, JSTOR.

- Teresa Palomo Acosta, “Hauschild Music Company,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, accessed March 28, 2021.

- Mary Ann Villarreal, Listening to Rosita: The Business of Tejano Music and Culture, 1930-1955 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press), 92.

- Tyina L. Steptoe, Houston Bound, Culture and Color in a Jim Crow City (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016), 85-89.

- Villarreal, 41-42.

- Ana Carolina Castillo Crimm, De León, A Tejano Family History (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003), 79-80 & 230.

- Craig H. Roell, “De Léon’s Colony,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, accessed March 28, 2021.

- Villarreal, 94.

- Manuel Peña, Orquestas Tejanas: The Formative Years: 1947-1960, Arhoolie Records, 1992, liner notes, 11.

- San Miguel, Jr., 47-49.

- Raymond Starr, Goliad (Charleston: Images of America, Arcadia Publishing, 2009), 78.

- Steptoe, 89.

- Starr, 74.

- Henry Wolff Jr., “Three Generations of Music,” Victoria Advocate, April 27, 2008.