Ornette Coleman: The Territory and the Adventure

By Maria Golia (London: Reaktion Books, 2020)

The history of jazz is often a tale set in the hip bunkers of the East Village, 52nd Street, or uptown in Harlem, yet its fabric so frequently coalesced in Midwest urban centers like Detroit and Chicago and southwestward to the plains states and beyond. North Texas cities Fort Worth and Dallas saw a host of their young jazz modernists find employment with territory bands or venture for New York and Los Angeles in search of greater opportunities, but not before paying their dues in dance or rhythm & blues bands at local joints of varying repute. In her new biography, Ornette Coleman: The Territory and the Adventure, Maria Golia seizes a pivotal moment and place in jazz history, not on 52nd Street in New York or Central Avenue in Los Angeles, but in an unnamed, all-white nightclub in Fort Worth with a young, hirsute, and curious saxophonist playing alongside fabled tenor giant Red Connors. As the laconic chords of “Stardust” slowly ushered dancers across the floor and his moment for a solo approached, Ornette Coleman experienced an epiphany. Rather than building a solo around melody that adheres to and anticipates chord changes, Coleman “literally removed it all and just played.” Coleman’s radical reinterpretation of “Stardust” got him fired from the gig, but his adventure had begun.

Following John Litweiler’s Ornette Coleman: The Harmolodic Life and Dave Oliphant’s Texan Jazz and Jazz Mavericks of the Lone Star State, Golia’s work picks up where her colleagues left off, charting the course of Coleman—not to mention other free jazz stalwarts of North Texas origin like Dewey Redman, Charles Moffett, and Bobby Bradford—as he navigates the burgeoning fields of radical improvised music and forges his harmolodic adventure. Demanding not only melodic but rhythmic and harmonic improvisation in equal measure, as well as what Coleman describes as “the use of the physical and mental of one’s own logic made into an expression of sound to bring about a musical sensation of unison executed by a single person or with a group,” harmolodics provided Ornette, his band, and his disciples a profound improvisatory language and philosophy. The Territory and the Adventure not only theorizes Coleman’s playing and purpose; it is a book deeply concerned with the “sonic and social ambiance of Ornette’s youth” in Fort Worth and surrounding areas. Golia notes, too, her book is “more a compendium than a comprehensive biography or technical analysis.” It is this frame in which Golia proceeds to “describe some of the pivotal places, people, and struggles that shaped [Ornette’s] music and his life.”

Golia places ample attention on Coleman’s early discoveries in Fort Worth’s beer joints and dancehalls, as well as the art and enterprises of Fort Worth’s mid-century African-American community. She details Fort Worth’s Black neighborhoods such as the historic Southside and, in the midst of wealthy west Fort Worth, Como, home to the venerable Blue Bird Lounge. The musical happenings at Fort Worth’s Black-owned Jim Hotel, which saw T-Bone Walker and his group appear as a house band, are also sketched. This focus on the musical landscape from which Ornette emerges, along with the struggles, rejection, and guilt he faced while playing professionally in nightclubs for raucous crowds, makes Golia’s work an invaluable contribution not only to Coleman scholarship but also to the history of African-American music, culture, and commerce of mid-twentieth-century Fort Worth.

Coleman bounced between Fort Worth, Los Angeles, and regional stages on the rhythm & blues circuit in the 1950s, but his 1959 arrival in New York City galvanized his harmolodic project. Golia vividly recalls the Coleman quartet’s residency at the Five Spot in New York. Following lengthy appearances from Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane, as well as fellow free jazz stalwart Cecil Taylor, Ornette stormed onto the Five Spot stage with trumpeter Don Cherry, bassist Charlie Haden, and drummer Billy Higgins, leaving audiences and fellow jazz musicians either dazzled or dismayed. As lines formed around the block, Ornette led a band whose improvisational adventures spoke to the title of the group’s 1959 LP The Shape of Jazz to Come. Golia moves rapidly from Ornette and company’s Five Spot gigs to the mid-sixties, a period in which Coleman reshuffles the deck after his groundbreaking Atlantic discs. She supplies much needed evaluation of Coleman collaborators like bassist David Izenzon and tenor saxophonist Dewey Redman. And, of course, there are Coleman’s late-sixties Blue Note sessions with his not-yet-teenaged son Denardo on drums and even appearances in the 1980s with Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead. It’s fascinating to learn how Coleman developed musical and spiritual rapports with his diverse and lauded collaborators, and it speaks to the profound influence Coleman had on developments in jazz and improvised music as well as rock and punk.

Perhaps the most surprising element of Golia’s book is the documentation it offers on Fort Worth’s Caravan of Dreams, “a world-class performing arts facility ‘designed and managed by and for artists.’” Caravan was a massive 131,000-square-foot venue with multiple bars, stages, functional spaces, and lodging for staff and visiting artists. Topped with a 165-foot geodesic dome under which a garden of cacti thrived, Caravan of Dreams sought to establish an artistic antidote to the creeping conservativism of the moneyed elite in Fort Worth. Golia, who managed and lived at the venue for many years, offers keen insight into this radical nightlife venture in the midst of downtown Fort Worth’s revitalization. When plans for the venue’s opening week were established, it was no surprise to see Ornette Coleman, the Fort Worth native, leading the festivities with such noted guests as writers William Burroughs and Brion Gysin and early Coleman collaborator James Clay from Dallas.

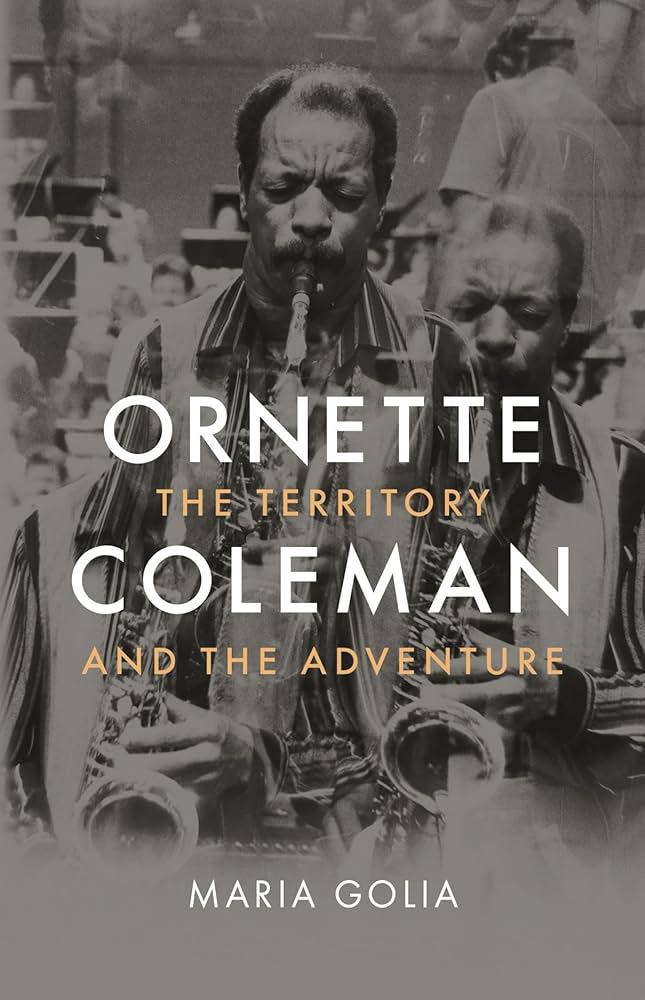

Maria Golia has assembled a valuable oral history, too, for much of The Territory and the Adventure benefits from her own recent correspondence with such key figures as trumpeter Bobby Bradford and numerous published interviews with Ornette, Dewey Redman, and Denardo Coleman. Golia writes with precision and humor; she coolly details the various proceedings of Ornette’s musical worlds, and she happily recognizes Coleman’s wit and whimsy, reminding the reader of his many witticisms, maxims, and scathing indictments of the music industry. A slew of images from noted photographers such as Ira Cohen rounds out the work. Reaffirming Ornette Coleman’s place as one the most important figures in avant-garde music, Maria Golia’s book offers an expedition into the history of North Texas music, free jazz, and the outer reaches of Coleman’s improvisational adventures.

-Alan Schaefer