“¡Vamonos pa’l Chuco!”: Punk Rock, Power, and Memory in El Paso, Texas

Tara Lopez

If “El Paso is the city that Texas doesn’t want,” writing an article for the Journal of Texas Music History presents itself with obvious complications.1 El Paso is geographically situated within the borders of Texas, but in so many ways, socially, culturally, and musically, it transcends, and is defined by, its sense of place. Located at the apex of several different borders, one with the state of New Mexico, and one with Juárez, Mexico, its identity is shaped by Texas, New Mexico, and Mexico, but it is something more. Its common name, El Chuco, best embodies its transcendence and its rootedness to this area. With a Latinx majority population in a state that embraces an Anglo, cowboy image, its nickname does reflect its demography, but the nickname also reflects something more.2 El Chuco touches on the uniqueness of its culture. It is Texan, but not. New Mexican, but not. Mexican, but not.

In this article I will follow the complex contours of this city through one crucial aspect of culture: punk rock in the 1990s. A musical revolution that emerged in the 1970s out of the UK and the United States, punk eschewed the grandiose pretention of progressive music for a raw and vitriolic sound, deeply rooted in a do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos. British bands like X-Ray Spex and the Raincoats embodied punk’s explosive energy at its inception. The voice of X-Ray Spex lead singer Poly Styrene, born Marianne Elliot-Said, for instance, was compared to a “weapon” and exuded the rage and irreverence of first wave punk, which found resonance with American counterparts like the Bags and the Zeros.3 By the 1980s, different permutations developed, such as the hardcore of Bad Brains and Black Flag; the straight-edge punk of Minor Threat; and by the 1990s, Riot Grrrl punk of Bratmobile, Huggy Bear, and Bikini Kill. Afro-Punk of the 21st century is yet another powerful wave revealing that punk continues to live, breathe, and evolve.4

In the 1990s, in particular, cities like Washington D.C., Olympia, and Seattle developed distinctive sounds, which deeply imprinted a geographic stamp of emerging musical movements. The connection between a site and its sound is common. Geographer Ray Hudson, for instance, sees places not as fixed and immobile, but as “porous” and constantly in the process of becoming. For Hudson, music “plays a very particular and sensuous role in place making.”5 Therefore, to understand El Paso, we must follow how music, and punk rock in particular, was pivotal in reconfiguring the city in creative and dynamic ways. Nineties El Paso punk was fierce, unapologetic, and fun. It emerged in different areas of the city, such as the Lower Valley with bands like the Shimpies, V.B.F., Debaser, Sbitch, and Fixed Idea. The sound reverberated through a city where the DIY ethos inspired a rich backyard show culture, featuring places like the Arboleda House, and with homegrown labels like Yucky Bus and Oofas! Records. The West side of El Paso was also teeming with bands like Jerk, Marcellus Wallace, and At the Drive-In. The connection with Juárez did not go untouched as bands like Los Paganos and Revolución X played on both sides of the border and made this scene international in scope.

Unlike other Texas music scenes such as Austin and Houston, however, critics and scholars have overlooked the El Paso scene. The indifference to punk in El Paso is, in part, due to a deeply entrenched understanding of punk as “white boy music.” While journalists are partly culpable, this racialized and gendered myopia is partly due to the origins of academic study of subcultures, which emerged from the UK’s Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, commonly referred to as the Birmingham School. Dick Hebdige’s Subculture: The Meaning of Style provided a path-breaking study of the subculture; nevertheless, he sidelined race and reggae as punk’s “present absence” and went further to assert that the divisions between black and white British youths reappeared as a “rigid demarcation” between the two, despite reggae and Black British influence on punk.6 His counterpart, Angela McRobbie, challenged gender exclusivity of such research and pushed the study to the realms of young women, too.7 By the end of the 20th century, Stephen Duncombe and Maxwell Tremblay’s White Riot: Punk and the Politics of Race interrogated this hegemonic view of punk and shed light on the contributions of women, queer musicians, and punks of color to both the development of punk music and the scene.8 Therefore, the diverse, Chicanx-dominant El Paso punk scene exemplifies the reconsiderations of such academic developments. Michelle Habell-Pallán writes, “Like Chicano/a art, punk makes a space for the critique of social inequality and racism, but mainstream representations of punk represent punk culture as a monolithic, white-boy-only-fad. In fact, punk had various and competing strains; it was not one thing.”9

Therefore, what will follow is a snapshot of one such “strain” of punk that emerged as a vibrant music scene in the 1990s. Despite recent attention to Beto O’Rourke’s former band, Foss, and nationally successful bands such as At the Drive-In, the grassroots sound is deeper and layered and points to a more textured picture of the city and its sound. The sounds and rhythms that reverberated through the ditches and valleys of the city were rooted in intersecting networks of people all focused on music, its production, and its performance. As Lucy Robinson, et. al. note, “The popular-cultural voice is a driver in community response to the world we live in. Music builds communities, makes sense of the world and finds ways of describing, articulating, and enacting change.”10 In the 1990s, young people in El Chuco were creating communities of sound, especially in punk rock, that were transforming the geography of their city and the terrain of music and memory.

History of 1990s El Paso

Historian Monica Perales frames the complex identity of the city: “El Paso was not just the dusty ‘Wild West’ outpost that local and regional historians too often emphasize. El Paso was also the nexus of vast transnational and transborder capitalist industries, a critical railroad, mining, and smelting hub through which capital in the form of ore, money, and labor poured into the United States.”11 Here, Perales critiques the misconception of El Paso as backward and isolated. Rather, several key events in the region mark the profound importance of the city nationally and internationally, especially in the 1990s. One of the pivotal events was the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA, on January 1, 1994. NAFTA had a devastating effect on El Paso’s economy with El Paso becoming the number one US city for NAFTA displaced workers, displacing a total of 24,000 workers from 1994 to the 21st century.12 Second, the eruption of the Zapatista rebellion that coincided with the implementation of NAFTA solidified anti-neoliberal movements locally and internationally. Third, in July 1997, Amado Carrillo Fuentes, the leader of Mexico’s largest drug cartel and responsible for importing as much as 70 percent of the cocaine that entered the US, died while undergoing plastic surgery to evade the authorities. His death sparked a turf war for the drug market with Juárez being the central theater for this battle. It would prove especially vicious considering that 450 gangs were said to already be operating in Juárez by the time of Carrillo’s demise.13 Fourth, within this context of economic and political upheaval, the bodies of mutilated women began to appear in the desert along the border with Juárez. Amnesty International estimates that 370 such femicides took place in Juárez from 1993 to 2003.14 Fifth, a revolution in immigration enforcement originated out of El Paso in the 1990s. Chief Patrol Agent of the El Paso Border Patrol Sector, Silvestre Reyes, pioneered “Operation Hold the Line” on September 19, 1993, which refocused enforcement from pursuing undocumented Mexican immigrants to reinforcing and defending points of entry into the United States, which “became the model for subsequent Border Patrol enforcement efforts at key locations along the Southwest border.”15 All of these events set the context for this punk scene, and the tendrils that began to emerge in the 1990s would come full circle in the following decades. For instance, Silvestre Reyes’s political career in the US House of Representatives would come to an abrupt end when he lost to former El Paso punk Beto O’Rourke in the 2012 Democratic Party Primary, and later the US seat, in 2012.16

“Angels with broken wings”—Belonging, Sound, and Solidarity

“Skating is, in part, about the redefinition of life. When you’re on a skateboard and everyone else sees sidewalks, I see runways.” Ian Mackaye of Fugazi17

“Now if you want to seize the sound, you don’t need a reservation. “Target,” from Fugazi’s LP Red Medicine, 199518

Music provided a gravitational pull for teenagers to meet and transform their worlds. The need for connection was strong, and punk articulated that hunger. This feeling of marginalization united them, and punk was that open sanctuary for those in El Chuco. Friendship was one central opening into punk. Erica Ortegón describes how she and her friend Lindy Hernandez “discovered punk and the punk scene together. We just went with it and learned about music, ethics, and everything about punk and the scene.” Ortegón and Hernandez would eventually form the Shimpies and played “a hand full of shows from 1998 and 99,” and it were these types of bonds that exemplify the intimate scaffolding that helped to create a vibrant punk scene.19

Another gateway out of social pressure and into punk was skateboarding for the young men in the scene. David A. Ensminger emphasizes that there was a “collusion” between skateboarding and punk that “transformed the local landscape and their relation to commodities, media, sports, and entertainment by forming a micro-economy, even micro-society.”20 In El Paso, Ensiminger’s “collusion” between punk and skateboarding was apparent. For instance, Jim Ward from At the Drive-In and Sparta explains, “Skateboarding and punk back then were intertwined.”21 Some of the most obvious overlaps were skate compilations that featured “skate rock,” much of which was punk and served as an introduction to the music for a generation of skaters.22 Furthermore, for the men whom I interviewed, skateboarding provided a space for them to find physical expression if they were not interested in football or basketball. According to Fill Heimer, “I was really an awkward kid, but with skating, it didn’t matter.”23

Skateboarding not only allowed a space for these young men to fit in, but it also allowed them unfettered access to traverse the physical terrain of El Paso and to explore powerful and lasting emotional connections. Michael Morales notes how he and his friends would skate all over El Paso and have fun, but also talk and bond. For Morales, skating was “an exploration of thought,” too.24 He emphasizes the necessity of such conversations:

Of course, we talked about girls. But we also talked about our strained relationships with our families. All of us seemed to be subject to a lot of verbal and emotional abuse, which turned physical amongst a few of us within their households. We got blamed for everything at our homes. That was a common ground we shared. These guys were also the first people with whom I was open about my mom’s schizophrenia, and they were all supportive. They were also the first friends I had sleep over. I gave them the mental prep before coming over, but it was really awesome. I finally had a support system.25

Resonant with the sociological research of Michael Kimmel or the studies in youth psychology by Niobe Way, young men desire emotional outlets and support, and friends play a role that cannot be underestimated.26 Skateboarding, therefore, led young men to punk, and also to lasting friendships.

Support in adolescence for both young women and men emerged in this scene and found a focal point in punk music. Bands like Fugazi and Minor Threat that came out of Washington D.C. were two of the bands most often cited by members of the El Paso punk scene, along with West Coast bands like the Descendents, Bikini Kill, and Jawbreaker. Others included the Sex Pistols, the Misfits, Metallica, Bad Religion, Concrete Blonde, and Crass.

Emotional alienation, compounded by the inequities of classism, racism, and homophobia, found resonance in punk. “The music, first of all, spoke to us…There was like a lot of anger and aggression, and that just suited well with me at the time with the trouble I was going through in my own life,” explains Jessica Flores.27 Ernesto Ybrarra reflects that it was punk’s “uniqueness and rawness” that drew him to the music. He adds that “punk gave me a reason to not feel bad about things I could not control.”28 Jason Cagann reiterates that point because the Descendents, for him, simply made him feel, “like a normal person.”29 Erik Frescas’s first experience listening to punk resonates with the profoundly intimate and transformative power it had for young people:

I remember, specifically…my freshman year of high school and playing on my Walkman the first Fugazi song I ever heard…It was [on the album] 13 Songs. It was the very first song on the record. Like I remember exactly where I was in my life at that exact moment. It was really that moving and life changing. And to this day, I remember exactly where I was at in my life when I hit play.30

Social dislocation amplified the connection to music and the ensuing community. Erica Ortegón notes how “we were like the misfits of the school…We couldn’t relate to like all the kids who were dressing in name brand clothes…It’s stuff we really couldn’t afford.”31 Luis Mota reflects, “I’m a gay male, so I was never really included. All the jock people were really just homophobic,” so his friends Martha and Yvette, who were into alternative music and skateboarding, provided a welcome sanctuary.32 Music has this visceral quality to it, and punk in El Paso became a refuge for all these intense emotions and marginalized identities to flourish as a cohesive community.

Along with music, fanzines were central to igniting passion for the music and creativity. Mundo, who lived both in Juárez and El Paso at different times in his life, describes how the shows and zines were magnetic:

Once you go to a show, you start to know about more shows because you get flyers. There’s people that have fanzines. I didn’t make any friends that night, but it was exciting…I had this sense of empowerment by looking at all these kids doing all these things like doing the fanzines and doing shows on their own, things that I wouldn’t imagine at the time that a kid could do.33

This sense of empowerment infused the music and zines and inspired a scene unique to the city. Alex Martinez writes in the El Paso Punk zine, “I’ve never read any zines covering the scene at all. I think everyone has been too busy worrying about D.C., San Francisco, NY, Fucking Seattle, and whatever other ‘important’ town.” He goes further to explain that despite “how bad El Paso sucks, there is so much around here to be covered here!… Like my friend Nora put it, ‘This is virgin territory for making a permanent dent for the punx!’”34

Such urgency led to an explosion of local bands like Sbitch, VBF, Jerk, Not So Happy, Fixed Idea, Los Perdidos, and Potato Justice, just to name a few, with the influence of punk throughout the nation and a sound that was all its own. In particular, Chicanx culture permeated the sound and how the bands described themselves. In the 1994 volume Book Your Own Fuckin’ Life, for example, VBF, or “Los Vaginal Blood Farts,” describe their music as: “In your pinchi face crazy D.I.Y. punk rock, holmes!”35 The use of such pocho Spanish like the misspelled “pinchi” and informal “holmes” illuminates the Chicanx core of El Paso DIY punk rock.

In an interview with Cedric Bixler-Zavala from ATDI and the Mars Volta, for instance, both the interviewer, Damian Abraham, and Bixler-Zavala note how the dominance of more celebrated metropolitan scenes really made it difficult for ATDI to find a place in the national music scene:

Abraham: “That’s why it is always such an amazing sound that At the Drive-In kind of came to because it sounds like nothing else because it seems like a bunch of different styles of song writing meeting in the middle.”

Bixler-Zavala: “The way you describe it—that’s perfect because we [ATDI] were so obsessed with some of the West Coast stuff that was being called ‘pop punk’ or whatever…Then, we were obsessed with Dischord, too, so we described it as, ‘Yeah, so we’re obsessed with both coasts, but we live in Texas.’”36

El Paso punk Chris Banta reaffirms the unique sound that emerged out of the city. For Banta, “El Paso is so diverse, but it is so specifically a border town.” The punk scene wasn’t simply just “white Western, military, or Hispanic.” For Banta, the music defied these categories, with a sound all its own.37

While the distinctive sound in the city ranged from ska to hardcore to emo, the music provided a focal point for fun and connection. Hardcore was one of the dominant sounds of the city in the early and mid 1990s. Jenny Cisneros, the lead singer of hardcore band Sbitch, loved female-fronted bands like Antischism, Bikini Kill, and Siouxsie and the Banshees. She notes, “The style of music, you know, was aggressive and loud and screaming and all that stuff, which I think took some people by surprise. Possibly, they didn’t expect for me to sound like that or whatever…I feel that people were like impressed by the screaming I could do.”38

In the mid 1990s, emo began to eclipse hardcore. Marissa López traces the origins of emo out of hardcore bands like Fugazi, but she notes that term is contested since many Fugazi fans would reject the emo label for its association with “seemingly watered-down, apolitical aesthetics.”39 In a texting conversation with four El Paso punks, Fill Heimer further questioned the foundation of such labels in music:

Fill Heimer: “What’s emo really? All the bands emoted. That was pretty much the thing we had in common. Mostly anger…Love.”

David Lucey immediately responded: “I think the scene didn’t really care about what was played as long as you hated Fill.”40

The ties of humor and fun are still apparent in these relationships and were also infused into the music. The band Fixed Idea, for instance, pushes forward this need for fun in the song “Chucotown Ska”:

I went to a ska show just last night

It didn’t suck, it was alright

I saw the prettiest thing I’ve ever seen

I had to ask her to dance with me

We started dancing, I hold her tight

Till she asked me about animal rights

I told her I couldn’t really care

I want to see her in her underwear

It was over, we went outside

And we kissed all through the night

I asked her to give me a little chance

I only wanted true romance

I don’t give a shit about animal rights

Just wanna dance with my baby tonight

Because the bass is thumping everybody’s pumping

To the heavy, heavy sounds of the heavy, heavy Chucotown ska

Don’t give a shit about animal rights

I’m gonna party on the hilltop tonight41

The thirst for fun also tied into the deeper need for solidarity that developed in the face of physical threats. For example, skaters and punks were visible targets for “jocks and cholos,”42 but, if punks were targeted, especially at shows, Ernesto Ybarra notes, “We all had each other’s backs.”43 For Jessica Flores such connections were central: “You know as an adolescent, you’re always looking for that group to feel part of something, and I knew it after my first show there [in El Paso], it was like being a part of something I was looking for.”44

Mikey Morales describes how he and other punks and skaters in El Paso at the time were “angels with broken wings.”45 Whether fleeing the ravages of classism, racism, sexism, homophobia, or just an overall disconnect with mainstream society, punk provided, and these El Paso punks forged, a site of creativity and solidarity. Nevertheless, the regionalism inherent in the city would also appear in the scene. Therefore, what will follow is an exploration of how these larger punk connections were rooted in disparate parts of the city but would eventually coalesce in a larger sense of unity of sound and connection.

The Geography of Sound in “El Chuco”

The punk scene was localized in different pockets around the city. The Lower Valley, and the West Side, in particular, were rooted in more than a century of class and racial segregation. In the early 20th century, city officials pushed forward measures to relegate Chicanos to South El Paso. By the 1920s the lasting legacy of the Ku Klux Klan’s domination of the El Paso school board assured that segregation would be solidified in the educational system. Their justification was a potent and pernicious form of eugenics. According to historian Monica Perales, “administrators and psychologists justified the separation of Mexican students into distinctly inferior facilities on the grounds that they were mentally incapable of succeeding in American classrooms.” Moreover, such misconceptions inspired city officials to also pass ordinances that were aimed primarily at Mexicans, and which prohibited them from congregating on city streets and sidewalks.46 At exactly the same time, however, a nascent pachuco subculture was emerging from the corner of 8th street and Florence in South El Paso.47 Pachuquismo was a subculture most often associated with Mexican-American women who dressed provocatively and donned pompadours and men who wore Zoot suits. Pachucos spoke a caló form of slang.48 Although much more multiracial in composition than commonly noted, pachuquismo was a force of cultural and political resistance against such overt forms of white supremacy in the early to mid 20th century.

Decades later the legacy of such divisions and cultural resistance would provide a backdrop to the local punk scenes that emerged, such as those in the Lower Valley and West Side. These punks would seize the power of space and eventually unite the scenes in 1996 and 1997 as they defied these borders with skateboards and guitars.49 Such geographic and sonic transgressions amongst the Lower Valley and the West Side punks, furthermore, were both rooted in a collective approach to music, which is resonant with Howard Becker’s concept of “art worlds,” which, for Becker, reveals how art is a “form of collective action.”50 Therefore, despite their distinctive demographics and characteristics, El Paso punks’ “art worlds” and their collective creativity is what fueled their music and eventually united them.

The Lower Valley

Other than geography, the key division between the Lower Valley and West side punk scenes was social class. Situated in the southeast part of the city near the border with Juárez, the Lower Valley was historically working class and poor. Today, approximately one-third of the people in this area live at or below the poverty level, reflecting long-standing economic struggles of the area.51 The area’s socio-economics, nevertheless, intersected perfectly with punk DIY values practiced not only due to economic scarcity and philosophical imperative, but also in alignment with key values of Chicanx culture. Michelle Habell-Pallán argues that the DIY punk values “found resonance in the practice of rasquache, a Chicana/o cultural practice of ‘making do’ with limited resources; in fact, Chicano/a youth had historically been at the forefront of formulating stylized social statements via the fashion and youth subculture, beginning with the Pachucos and continuing with the Chicana Mods in the 1960s.”52 Punks throughout El Paso, and especially in the Lower Valley, utilized this rasquache to create their own record labels and music venues.

The intense focus on creating the music they wanted to hear inspired punks to create their own record labels. Fill Heimer’s label Oofas! Records carried bands like Fixed Idea and the Hellcats, while Ernesto Ybarra’s Yucky Bus put out nine 45s and had bands like VBF, Short Hate Temper, Potato Justice, and the Chinese Love Beads.53 Ybarra’s ad in the 1994 issue of the national zine Book Your Own Fucking Life shows how such publications were essential to promoting these labels:

YUCKY BUS WRECKIDS

c/o Urnie Ybarra, xxxx, El Paso, TX 79907. (915) xxx-xxxx

DIY label interested in putting out underground bands for the fun of it. VBF 7" and Short Hate Temper/Potato Justice split 7" out now.

YUCKYBUS WRECKIDZ/GUIDO VASELINE PRODUCTIONS

xxxx, El Pisshole, TX 79907. (915) xxx-xxxx (Urn)54

Venues for live music were scarce in the early 1990s. Bars and clubs were known to have a “stranglehold on the shows,”55 and since most of the kids in places like the Lower Valley did not have cars, a very local scene developed with kids living within a three- to four-mile radius. Garages and backyards became the central venues. For example, when Ernesto Ybarra started to book bands from out of town to play, his grandparents graciously provided the band members a place to stay for the night. Despite limited resources, Ybarra’s grandparents “were the foundation” for him. Moreover, his focus was not on profit: “It was not about making money. It was about DIY ethics.”56

One of the key focal points of this vibrant live music culture in the Lower Valley was Erica Ortegón’s house. Described, in retrospect, as “the scene’s safe space . . . where we could all congregate and not really worry about getting gawked at or picked on,” this place became a cornerstone of the Lower Valley scene.57 Ortegón relates that she first proposed having shows at her house by insisting that her mom allow her to invite bands to her birthday party. Her sister’s support and Ortegón’s good grades in school finally convinced her mother to let her have the bands come play.58 One show turned into several, and her backyard transformed into a DIY venue known as the “Arboleda House.” Managing crowds and people could prove difficult. When one show was winding down, for instance, a neighborhood friend told Ortegón that a guy who had most likely been at the show was going around with a knife and slashing tires on neighbors’ parked cars all over the cul-de-sac.59 Ortegón did her best to keep the peace with neighbors, but after an especially loud show, her mother was fined $200, and her ability to put on shows was in peril. Ortegón recounts this particularly difficult evening:

I remember one of the last shows. It was Fill [Heimer] actually who was determined to have a show on a Wednesday. And I was like, “Nah, dude, I don't think we can do it.” And he's like, “Well, there's nowhere else.” And I'm like, “Well look for other places first.” And I don't think he could find anything. So we did it. The cops got called. And once the cops get called, you would end it. But then I think we didn't. So it kept going till the cops came again. And then I remember my sister coming out. She's like, “I hope you're happy!” I went to go to the front of the house. And sure enough, I saw the cop writing down something. We did have to pay a fine. But Fill was totally cool about it because he helped us out. Like he wrote a letter to whoever needed the letter to give us an extension or a payment plan. And I think after that we had one more show, to get money to pay for that citation.60

In Lindy Hernandez’s zine Candy from Strangers, Ortegón also called on kids in the scene to help pay the fine by appealing to their memories of “all the good times . . . WYNONA RIDERS, HICKEY, BRISTLE, zine distribution, shows, ALL the locals, the juice, the flat tires.”61 Despite the fine, she reflects, “It was fun! It was like these bands started coming to play…You know people would come in from all over town, so, like I said, you’d meet new people. It was more like . . . a community. The building of a community kind of thing."62 What Ortegón was building, along with others, was a DIY form of “social infrastructure.” Sociologist Eric Klienenberg defines “social infrastructure” as the physical conditions that allow “social capital” to develop. Like the backyards that encouraged a sense of community in El Paso, good social infrastructure, according to Klinenberg, “fosters contact, mutual support, and collaboration."63

Such backyard shows, like those at the Arboleda House, were the signature of the Lower Valley/Ysleta scene. Nevertheless, the police began to target these shows. Therefore, these Chuco punks had to be innovative and be versatile so the show could literally go on. Erik Frescas recounts one show that started in his own backyard:

One night, in particular, it's at my mom’s house, and there were these two bands that were pretty popular…So the night starts off a little bit strange. Like the bands show up, and my mom would always say, “If the cops show up, tell them I am out of town, and you’ll have to figure it out.” Ultimately, at the end of the night, there was like 200 people that showed up at my mom’s backyard. So the night starts getting crazier, and more people start jumping the gate…Even before the first band plays, the SWAT team and two helicopters get sent to my mother’s house. All chaos breaks loose. People start moshing and throwing themselves off the rooftop. And it gets moved two or three times, and out of 200 people, it ended being 20 people, and the band played in the middle of the night between some like apartment complex and a basketball court.64

The sense of community, connection, and just outright wild fun flourished at these shows, but there was also something more visceral at stake in these backyards and alleys. Fill Heimer emphasizes the profound emotional coalescence and transcendence that live music ignited. For him, shows were one of his “pillars” and presented “definitely a spiritual experience, sharing something together and becoming part of the bigger crowd."65 Jenny Cisneros, the lead singer from Sbitch, adds further that when playing shows, the experience could be equally profound. A show she played with Sbitch in Minot, North Dakota, for example, proved to be one of the best shows they played because that “show was crazy. I felt like these kids were starved for music or something…But they were just like the most energy I’ve ever seen at a show.” This feeling at shows was not uncommon. Cisneros says, “The energy is electric. I don’t know how you describe it. When you have a room full of people, you know, 100 kids, and everybody is feeling the same like that. It’s so moving."66 Barry Shank’s analysis of Austin’s scene resonates with the powerful experience of watching live music that Heimer and Cisneros point to here. Shank argues that moments of “collective musical pleasure…contain a promise that transcends any competitive drive for individual gain."67 Shows, therefore, provided intangible feelings of solidarity that were just as important as the physical sites where they were played.

The West Side

Such frenetic energy was also present on the West Side. While the two scenes will be analyzed as distinct entities, they eventually unified in 1996 and 1997. Two key people from El Paso High School, Jim Ward and Cedric Bixler-Zavala, would not only lead the West Side scene, but were key players, along with Lower Valley punks Ernesto Ybarra and Fill Heimer, in uniting the scene across these class and geographic divisions.68 In the El Paso Punk Zine, one contributor notes, “I’d like to add that at shows lately, there has been a sense of unity. I really like that, that we all stand together and keep the trouble makers away from the shows."69

Despite the eventual unification, the areas of town had significant differences. Compared to the poverty rate that hovered around 30% in the Lower Valley, on the West Side, and, in particular in the zip codes around Coronado and Franklin High Schools, the poverty rate was 16.3%.70 The West Side’s reputation as affluent obscured deep-rooted class and racial inequalities, however. This complex context gave rise to bands like Phantasmagoria, Out of Hand, Jerk, Marcellus Wallace, and At the Drive-In. While venues like the Mesa Inn were sites of key shows, West Side punks also booked shows near the University of Texas at El Paso, but for many West Side punks, the “East Side was where all the cool shows were.”71 For instance, Jessica Flores, who attended Franklin High School on the West Side, recognizes that others assumed she was rich and “had money” even though her family was poor.72 Despite that image, and being a woman, she became very involved promoting shows:

It’s really hard for girls to be a promoter. Like back then, it was. I don’t know about now, but back then, it was really hard. I would get people just telling me comments like, “This is a real good turnout for a girl promoter.” Just stupid shit like that. You know what I mean? And, so Luis [Mota] started getting most of the shows because he’s like a dude, y’know? And then I just didn’t have time for it. I was working. And I was trying to survive, and I wasn’t really going in the direction that I wanted to. I just kind of just stopped. I’m not saying that’s the line in the sand. Maybe it was me, and I didn’t want to do it, but it was probably a mixture of a lot of things.73

The marginality Flores describes resonates deeply with feminist analyses of women in subcultures. Angela McRobbie, for instance, argues that subcultures resign women to ancillary, and often derided, roles of backup singer and groupie.74 The shock at Flores’s skill as a “girl promoter” is indicative of sexist hierarchies and exclusions prevalent in broader society. Her reflection on her experience goes to the heart of women’s restricted roles in scenes like the 1990s El Paso punk scene:

For me there was like going to shows, and then, there was like being part of the scene. That’s the difference, and groupies just go to shows. If you’re part of the scene, and you’re a chick, you either sing or play bass. Right? Or you just go to shows, and I didn’t do either, so I just found my own way to do it.75

Like in other metropolitan scenes throughout the US, young women in El Paso did not readily have central roles in the scene and had to creatively forge their own spaces. Sbitch lead singer Jenny Cisneros, nevertheless, did have a unique role as a singer in a hardcore band but never felt any sense of exclusion. Therefore, the terrain for women in this punk scene was obviously textured with variation.76

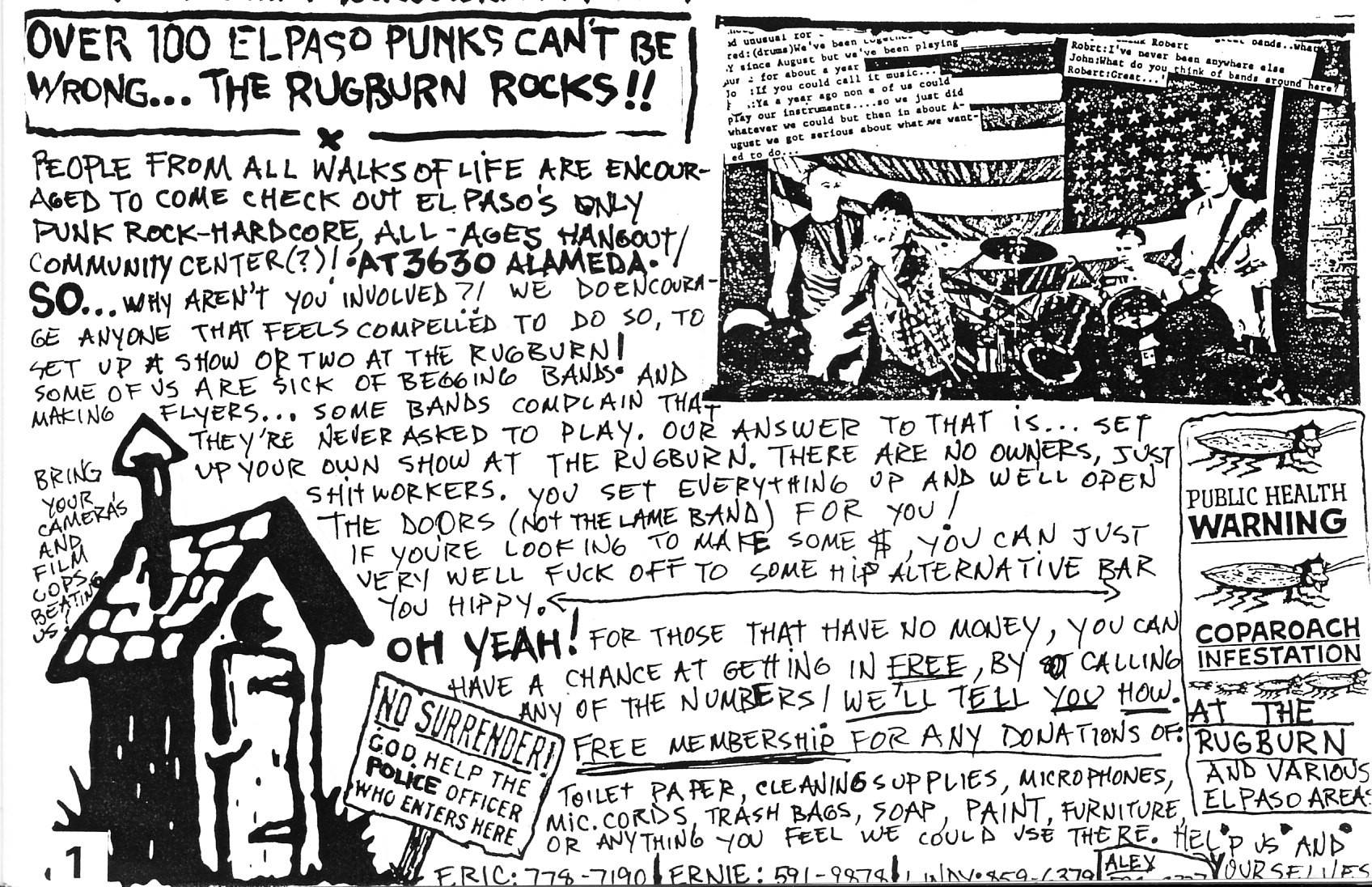

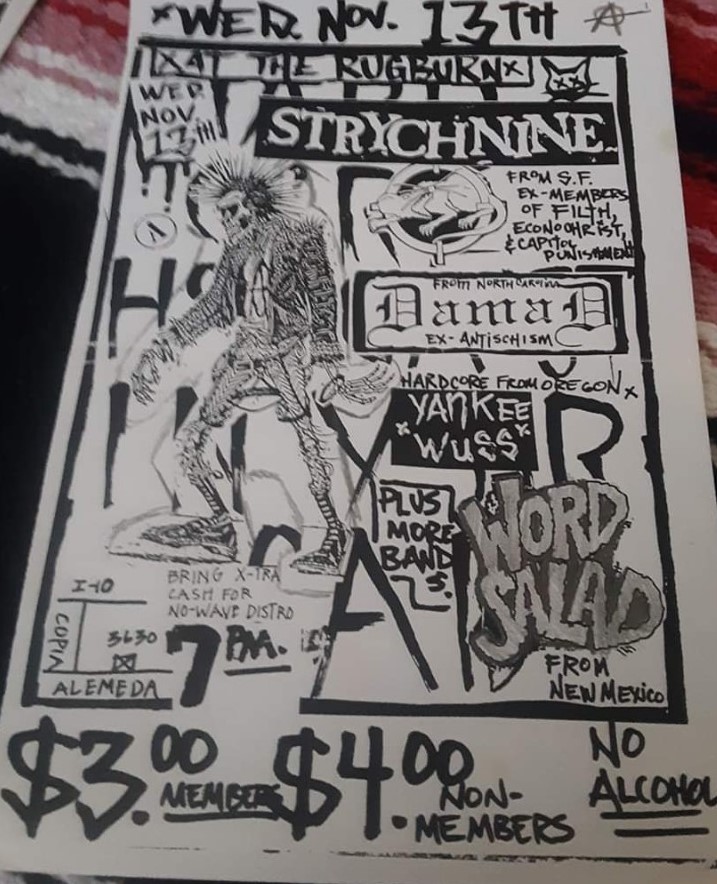

One of the key venues that started Flores’s pursuit of booking shows was the Rugburn. Lower Valley punks Alex Martinez and Carlos Palacios began to recognize that it was difficult for people to travel across town to see backyard shows, and now they also had really good but big equipment, so in both cases, moving around “was getting tiring.” Therefore, in 1996, the guys from the Fla Fla Flunkies put up the money to rent a car repair shop that was located on the main strip of Alameda Ave. Their choice was “strategic” because the Rugburn was just off a major exit on I-10, making it easily accessible. They then put their DIY ethos to work by sound-proofing the small venue by covering it with carpet and nailing upholstery sponge to the ceiling. They eventually realized the building was not only shared with another business, but the owner’s family lived in that building and had access to the breaker box. When shows became too loud, they would cut off the electricity right in the middle of a show. Martinez was able smooth things over with the family, and they began to send their son to sell peanuts and sodas during shows.77

Cramming punks from every part of the city into a small, hot building eventually would boil over into the “Rugburn Riots” of 1996. On November 13th of that year, a “pulverizing metal hardcore” show was booked with bands like San Francisco’s Strychnine and New Mexico’s Word Salad.78 There was an intensity in the air, and Jessica Flores decided to leave early: “You could feel it. You could definitely feel it. Something was going to happen."79 A fight then broke out in the parking lot, and one of Martinez’s friends decided to call the police. Five or six police cars immediately surrounded the Rugburn. According to Martinez, some West Side punks parked across the street and jumped into their truck to leave, and a police officer pulled out his gun and made the punks get out of the truck and started kicking one kid in the head. Martinez shouted at the police officer to stop and eventually was met with blows himself and was arrested.

Despite the brutality and chaos of that night, Martinez reflects on how the Rugburn was “a culmination of the kids from all the scenes coming together, all the different parts of town. I think that was the maximum, the Rugburn; that was like the peak, all parts of town coming together for shows.”80 Like with the Arboleda House, the Rugburn became a site of sound and connection that further solidified this scene, but unlike the Arboleda House, its location and purpose transcended the Lower Valley to connect punks throughout the city.

Tragedy, unfortunately, would also reaffirm these cross-city ties. Sarah Reiser and Laura Beard were West Side punks who defied the roles prescribed for women and formed bands like Rope and the Glitter Girls. In their final band, the Fall on Deaf Ears, Beard played bass and Reiser played guitar, with Clint Newsom also on guitar, and Cedric Bixler Zavala on drums, and all were on vocals. Jason Cagann, whose band Debaser played shows with several of Reiser’s and Beard’s bands, notes that while some in the scene ridiculed them for being women playing in bands, he emphasizes, “I think there was respect for what they were doing whether people realize it or not.”81 In 1997, Newsom asserted, “They were kind of mentors. I know they wanted to see more females in the punk scene.”82 When they formed the Fall on Deaf Ears, their reach extended beyond the local scene and the city limits as they opened up for bands like Propagandhi and Egon.83 Exhausted after returning from a tour on the way back from Austin, Texas, in 1997, the driver fell asleep at the wheel, and Reiser and Beard were thrown from the Nissan pickup truck and killed.84 “They were part of the punk scene here. They had a lot of friends, and the punk scene is pretty tight. Everybody is taking it pretty hard," noted one UTEP student interviewed in 1997.85 Jason Cagann reaffirmed this sentiment two decades later. He notes they “affected a lot of people in a profound way.” He adds further that “it was a coming together” since by 1997 “the West side and the Lower Valley were, you know, united,… so we kind of experienced it as a group."86

ATDI remembers Reiser and Beard’s deaths in the song “Napoleon Solo” with a hurt and raging despair that is indicative of the wound that their deaths left on the scene. Bixler-Zavala sings:

March 23rd hushed the wind the music died

If you can't get the best of us now

It's because this forever

Makes no difference our alphabet

Is missing letters

17 embalmed and caskets lowered

Into the weather

A drizzle brisk and profound

From this Texas breath

Exhaled no sign of relief

This is forever87

Lucy Robinson, et. al. emphasize that “Music is also how…events have been memorialized."88 “Napoleon Solo” embodies this effort to remember these two women and the scar their deaths left on a flourishing punk scene in El Paso.

“A communion of two scenes”—Punk and El Paso/Juárez—Sound and Politics

The differences between the East and West sides were set within the overpowering backdrop of an international border. El Paso and Juárez present the curious case of two distinct cities that beat with the same, albeit fractured, heart. They are both united and divided by history, a river, and a border. Historically, they were a unit. El Paso del Norte traversed both sides of the Rio Grande as an essential route for Spanish colonizers from Mexico to New Mexico and other parts of what is the now the American Southwest. The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo bifurcated the community after the Mexican-American War. Since then, El Paso and Juárez have existed in an intertwined, but staggeringly uneven, relationship. Juárez’s 1.5 million inhabitants, for instance, outstrip El Paso’s population of close to 700,000.89 On the other hand, while El Paso consistently has one of the lowest murder rates in the region,90 once again, after decades of the same, Juárez was deemed one of “the most dangerous cities in the world."91

The El Paso scene created a fluid relationship with the burgeoning Mexican metropolis across the border. Gloria Anzaldúa’s conceptualization of the borderlands best captures the cultural fluidity of the El Paso and Juárez punk scenes. She argues that “the U.S.-Mexican border es una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before the scab forms, it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of two worlds merging to form a third country—a border culture."92 The interplay and overlap of the El Paso and Juárez scenes, therefore, embodied this fused “border culture.” Alex Martinez of Faction X and Sbitch explains, “Being in the middle of nowhere allows you to carve out your own identity free from creeping influence of major city fads…Mexico was an added sphere of influence."93 Ed Ivey from the Rhythm Pigs describes how the band had made a deal with some punk in Juárez to share their electricity with them. According to Ivey, the band extended a cord linked to a generator across the Rio Grande to the Juarense punks who did not have the electricity for the show. Then, when the show started, the bands took turns playing to one another across the border.94

Later in the 1990s, ignited by punk DIY ethics, Mundo, a punk living in both Juárez and El Paso, and El Paso punk Erik Frescas, solidified an international connection between the two scenes. Mundo describes how zines like Maximum Rock n’ Roll and Profane Existence inspired him to engage in such an endeavor:

They would have like scene reports from other cities, and I thought, “Okay! I want that happening in my town.” So I was proactive, I guess, and I started to ask people that looked, that had a weird look or had a different look with their outfit to see if to see what they were into, and I would ask, “Hey! Do you know any punk bands? Do you know anyone that would want to throw a punk show in Juárez?” And every time I asked that, people were a little bit, not shocked, but like I guess me asking them was strange because a punk scene didn’t exist for them.95

This desire to forge a truly international live scene found expression when Mundo met Erik Frescas outside a bar called La Raya in Juárez. Frescas was handing out flyers for a show, and the subsequent conversation with Mundo culminated in nascent plans to book El Paso and touring bands in Juárez.96 Frescas was keen to collaborate with Mundo because he knew the power of Mexican audiences. He reflects how bands in El Paso were always “hoping for that Mexico crowd” since they were known to arrive, without notice, in busloads and bring an ideal presence to any live show.97

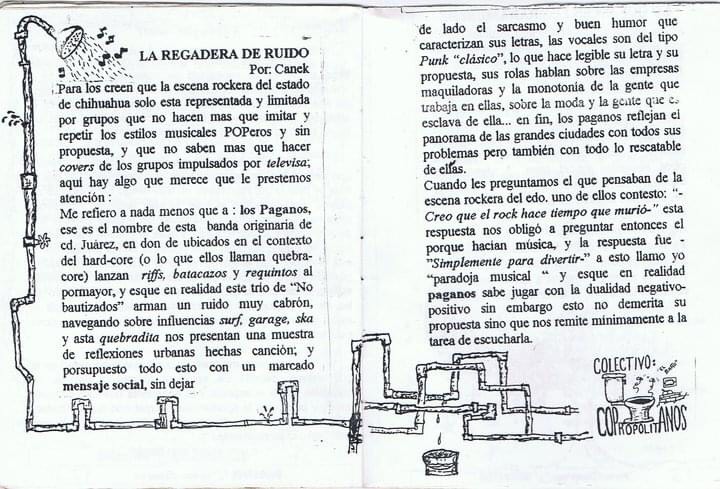

One of the first steps in attracting touring bands to Juárez was to advertise in the 1996 edition of Book Your Own Fucking Life. When bands responded to the following ad, Frescas would offer the bands to play only one show in El Paso or one show in El Paso and another in Juárez the following night. His ad read, “Will be able to hook-up bands with a place to play from clubs to back yards. I will try to provide food and or lodging."98 It was difficult, however, for bands to play in Juárez because upon returning to the States they would have to show receipts for the purchase of their equipment. If they could not produce those receipts, the Border Patrol could confiscate their instruments and amps. Therefore, Mundo took the next step of booking Juárez bands “under the premise that they would have to share their equipment” with the visiting bands.99 Once they gained momentum, Mundo and Frescas booked a host of El Paso bands like Los Perdidos, the Hellcats, Fla Flas, Debaser, Sbitch, and touring bands like Hickey to play in Juárez at a venue called Lencho’s Place.100 Being part of a group of people that created a blossoming international DIY punk community had lasting emotional resonance with the two. Frescas reflects that “a sense of popularity” did emerge from this work, but really it was for the love of live music and “just bringing people together.”101 Not only was Mundo proud of this collaboration and its success, it was part of how the totality of his DIY efforts were coming to fruition, especially once he started playing with his band Los Paganos:

In 1998 we played with Los Crudos in an art gallery, which for me was a big accomplishment because I mean I started reading about Los Crudos in a fanzine, and then, two years later, I was playing a show with them. And that’s mentioned a lot in the history of punk rock. And it sounds cliché, but it’s true. I lived it. So I’m really happy it happened. I’m very grateful of being given the opportunity that almost anyone can do it.102

Another band connected with Mundo and Frescas was the Juárez band Revolución X, which literally bridged the international border with its band members, but even more powerfully, its politics. Referred to by one Latin American journalist as “una banda fantasma (a ghost band),"103 it was fronted by poet and diplomat Gaspar Orozco. Originally from the Cd. Chihuahua, Orozco formed Revolución X on January 1, 1994. The Zapatista uprising in Chiapas, Mexico, was the inspiration for the band and its first album. For years, Orozco loved “the pure, brutal power” of punk rock and its inherent critique of “social injustice,” and he began recording songs with his friend Antonio Martinez in Mexico. Subsequently, Orozco sent out copies of the album primarily to contacts through Maximum Rock N’ Roll. Their music soon aroused the interest of bands like Los Crudos and Huas Crudos and Guasipongonterest of bands liek z. Subsequently, Orozco sent out copies of the album primarily to contracts trhousipungo.104 The political and musical ferocity were the hooks. The band’s song “I’m Making My Future with the Border Patrol,” for instance, eviscerates the racism and brutality of immigration enforcement:

I’m working happily with the border patrol

I’m so excited and filled with joy

I’m the friendly face of the land of the free

But if you want to get inside

I’ll kick out your teeth

I’m making my future with the border patrol

Beating Mexicans is so much fun!"105

Orozco later recruited El Paso punks Alex Martinez on bass and Jason Cagan on drums to play a handful of shows. For Cagann, Revolución X’s political hardcore was inspiring at a time when he was developing a social awareness from sociology classes he was taking at the college.106 Even though the El Paso version of Revolución X only played two shows, the effect of its music, and the song “I’m Making My Future With the Border Patrol,” is far-reaching, seen as “something of an anthem for Latina/o punks.”107 When Orozco re-formed the band around 2015 and was playing in Mexico City, he notes that “when we played the song of the border patrol, the people knew the lyrics, and they were singing it with me. It was something that we had recorded twenty years earlier!"108

Other resonances of cross-border politics continued to emerge throughout the 1990s. For instance, Bowie High School, considered a West Side high school, was the site of a lawsuit that eventually changed Border Patrol enforcement nationally. The successful lawsuit presented a host of cases where the Border Patrol, on Bowie High campus, or in the surrounding areas, were accosting and abusing Mexican Americans. One of the long-standing issues was how the Border Patrol maintained a hole in a fence at Bowie High School for undocumented immigrants to pass through so the Border Patrol could catch them, oftentimes, on campus. In Murillo, et al. versus Musegades, et al., filed in October of 1992, the plaintiffs successfully put forward that the Border Patrol had engaged in “egregious violations of the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which protects all persons from ‘unreasonable search and seizure.’” The court’s refusal to allow the Border Patrol to operate so extensively, and illegally, on the US side of the border eventually led to the rise of Silvestre Reyes and the creation of his “Operation Hold the Line” that sought deterrence at the border itself.109

Such border politics emerged in El Paso bands’ music, too. West Side punks Cedric Bixler-Zavala and Jim Ward formed At the Drive-In in 1994. With a mix of Chicano, Puerto Rican, Anglo, and Arab musicians, they reflected the dynamism of the El Paso punk scene. In the early 2000s the band was picked up by a major label and recording in Los Angeles, yet their music was still tied to El Paso and, in particular, the mass murder of women along the El Paso/Juárez border. These femicides were rooted in history of the area and coincided with the cataclysmic economic and political changes occurring in the area in the 1990s and early 2000s.

The 1960s Border Industrialization Program established the first maquilas, and they soon attracted migrant workers from across Mexico, especially women. With the signing of NAFTA in 1994 and the opening of markets, maquila employment increased from a little over 3,000 employees in 1970 to almost 250,000 in 2000. The attraction of these jobs fueled a threefold increase in the population of Juárez at the end of the 20th century.110 There was a change in the gender of the workforce, too. When the maquilas were first developed, 80 percent of the workforce was made up of women, but after 1994, women made up about half of the 200,000-strong workforce. Many of these women would become the victims of what eventually would be termed femicide that began to grip Juárez in the 1990s.111

According to Julia Monárrez Fragoso, femicide is “murder of women by men who are motivated by misogyny and is a form of sexual violence where you have to take into account: violent acts, the motives, and the inequality of women and men in economic, political, and social spheres.”112 More men were, and are, killed annually in Juárez than women. However, what distinguished femicides from other forms of murder was the level of brutality these women endured before and after their murder and the disposal of their bodies. The following murder in Juárez exemplifies the nature of femicide: “1995—An unknown woman that was 24 years old was found with the strap of woman’s purse around her neck, her neck broken, wounds on the right arm, with the right breast amputated and left nipple bitten off."113

The head of the National Citizen Femicide Observatory, Maria de la Luz Estrada, comments, “Hate is what marks these crimes. The bodies show 20 or 30 blows. They slice off breasts and faces and throw the fragments in the garbage. In a macho society like Mexico, authorities are always questioning what the women did. What was she wearing? Was she sexually active? This helps the impunity and lack of action."114 Despite the severity of the crimes, police authorities systematically downplayed the number of murders, ignored the pleas of desperate families, or impugned the reputation of the victims, asserting they were promiscuous women who invited their own demise. Furthermore, the effort to make these crimes fade into obscurity was central to the perpetrators’ efforts. Fragoso explains, “This aggression [femicide] is so common that the victims’ names or where they were killed are forgotten from one day to the next. Forgetting is part of what those who remain observers or those agents who execute the aggression do. As opposed to the victim whose feelings and body are marked with everything she has to remember."115

The first political steps activists in Juárez and El Paso took were to memorialize the victims, not allowing the public, and most importantly, the families and authorities, to forget them. Such tactics included protesting with pictures of the victims or the missing and the placement of crosses, especially pink crosses, where such femicides had occurred. At the Drive-In’s song “Invalid Litter Dept.,” and the accompanying music video, directly address femicide in Juárez, aligning the band with the posters and crosses that pose a resistant form of remembering. While the music video features the visible signs of resistance, the song itself is a scathing portrayal of cruelty and corruption in the distinctive setting of El Paso/Juárez:

And they made sure the obituaties

Shows pictures of smokestacks

Dancing on the corpses' ashes.

Not only does the image of smokestacks denote the random and industrial resting places of the murdered women, but they are so integral to the face of both cities, especially El Paso in the 1990s. On February 8, 1999, the Asarco smelter, representative of the former industrial strength of El Paso, closed.116 The resonance of smokestacks is both a commemoration of the anonymity of the murders, but also a reference to the industrial geography of El Paso and Juárez at the time.

The song then eviscerates Mexican officials’ perfunctory efforts to capture those responsible, thereby furthering the violence against the victims, as their hollow gestures simply service as “dancing on the corpses ashes”:

In the company of wolves

Was a stretcher made of

Cobblestone curfews

The federales performed

Their custodial customs quite well

Dancing on the corpses' ashes117

The critical power of the lyrics is a direct reflection of the frustration activists in Juárez faced. When the governor of the state of Chihuahua created a Special Task Force for the Investigation of Crimes Against Women in response to public outcry against the femicides, the director, Suly Ponce Prieto, came to realize that police had burned thousands of pounds of evidence; her office had been cleared of files related to previous investigations and bystanders and news reporters had been given unlimited access to crime scenes.118 At a live show, ATDI lead singer Cedric Bixler-Zavala emphasizes this criticism by introducing the song:

Where we come from is between two passes. It’s why it’s called El Paso. In between that border town, there are little secrets lying underneath the desert floor along the cactus written all over the highway…And this is for the women that have died in Juárez, Mexico. For anyone who wasn’t chickenshit enough to bring it up in the press. For you we sing it out loud, and we sing your name…And we hope that you just don’t become part of the “Invalid Litter Department."119

Lower Valley punk Mikey Morales describes the relationship between El Paso and Juárez punk as a “communion of two scenes,"120 where, in Gaspar Orozco’s words, punks created “an open, borderless community."121 Whether it was El Paso punks performing at Lencho’s Place in Juárez or sharing instruments or politics, the relationship was intimate and profound. At this site, Andzaldúa’s “border culture” of music fed into the uniqueness of El Chuco punk.

“Vamonos pa’l Chuco!”—Power, Punk, and Memory

“Places make memories cohere in complex ways. People’s experiences of the urban landscape intertwine the sense of place and the politics of space.” Dolores Hayden122

In the early 20th century, El Paso was known as such a den of illegality, or chueco, that it became commonly known as chueco and, eventually, transformed into its nickname: “chuco.” Mexicans travelling up to the city would exclaim: “Vamonos pa’l Chuco!” (Let’s go to El Chuco!). “Pa’l Chucho,” then, in turn, evolved into the word “pachuco."123 Despite surprise at the city’s subcultural creativity, its nickname adamantly declares its subcultural identity and resists historic amnesia of its roots. Its foundation is deeply intertwined with a tradition of cultural resistance, originating in the early 20th century, and is continuously being recreated and revived throughout subsequent decades.

Punks in the 1990s and early 2000s were part of this continual process of reclaiming El Paso and reconfiguring it into El Chuco. They did it, first, by transforming space. With skateboards, they escaped their neighborhoods and explored the city on their own terms. Their shows at places like the Arboleda House took the power away from bars and clubs and redesigned their backyards into central venues for live shows. They took car repair shops, outfitted them with discarded carpet, and created spaces like the Rugburn where punks from throughout the city could congregate. They bent international borders at their will by booking shows in El Paso and at Lencho’s Place in Juárez. These punks seized the space and recreated it on their own terms, thereby recreating El Chuco.

The multiracial, Chicanx-majority city created a scene that did not deny its Mexican roots. Ernesto Ybarra is adamant that people remember that “Mexican, indigenous, and poor kids” created this powerful scene.124 Moreover, women of color like Erica Oretgón, Jessica Flores, and Jenny Cisneros further fueled the dynamism of El Chuco punk. Pachucas and pachucos of the early 20th century forged cultural space and power among the powerless, and decades later, punks would do the same.

Despite divisions of class, race, and gender, these communities of sound forged emotional and creative connections that propelled the momentum of El Chuco punk. They created “a real kind of spiritual entity of the DIY ethic”125 and developed “a real sense of community that was inspiring.”126 While power and domination is about division and disconnection, the punks created a Chuco of something more: “We figured out that we could do it on our own, and we figured out that we needed and loved one another.”127

At the end of the nineteenth century, Anglo-run newspaper editors praised the erasure of Mexican power and culture from El Paso’s landscape. For them, “the removal of ancient adobe with all their bad associations means a new life for El Paso.”128 Nevertheless, George Lipsitz counters that “obliterating suppressed memories and desires requires constant vigilance,” and the memories of El Paso as El Chuco, pachuca and pachuco resistance, and El Chuco punk in the 1990s, have proved themselves as forms of cultural insurgency against such historical oblivion.129

Therefore, their memories are not novel pieces of trivia; they are a powerful force against a broader force of sterile but ruthless historical amnesia. Lipsitz underlines how memory is a terrain of struggle for marginalized groups, and how what he terms “counter-memories” are tools to fight against domination: “We may never succeed in finding out all that has happened in history, but events matter and describing them as accurately as possible…can, at the very least, show us whose foot has been on whose neck.”130

Like the history of pachucas and pachucos almost a century earlier, the El Chuco roots of this dynamic subculture of punk have been overlooked or just forgotten by others, but El Chuco punks’ “counter-memories” in their music, flyers, zines, and in this article, are a powerful force of remembering.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, an awareness of documenting this memory appears in At the Drive-In’s song “One Armed Scissor”:

Dissect a trillion sighs away

Will you get this letter

Jagged pulp sliced in my veins

I write to remember.131

While particular to one band, this lyric’s resonance is a powerful reflection of how these punks were part of almost a century-long rebellious tradition of reshaping El Paso into El Chuco. Moreover, it sheds light on the powerful way music connects beyond the present and does not allow us to forget.

Notes

1. Fill Heimer, interview with author, January 2020.

2. “Quick Facts: El Paso County, Texas,” United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/elpasocountytexas

3. Lucy O’Brien quoted in Emiliano Castrillón Mondragón, “Rupturas y continuidades en el concepto “ruido-no música” en la escena punk de la Ciudad de México,” unpublished thesis.

4. This is obviously not the hegemonic history of punk, but the standard narrative is not only ubiquitous and stale by 2020, but it resigns women, people of color, and LGBT folk literally to the margins of the narrative. Therefore, the most punk rock gesture is to mention the Clash, the Sex Pistols, and the Ramones literally in the margins for once. See Stephen Duncombe Maxwell Tremblay, eds., White Riot: Punk Rock and the Politics of Race (London: Verso, 2011); Maria Katharina Wiedlack, “‘We’re Punk as Fuck and Fuck Like Punks’: Queer-Feminist Counter- Cultures, Punk Music and the Anti-Social Turn in Queer Theory” (PhD. diss. Universität Wien, 2013).

5. Ray Hudson, “Regions in Place: Music, Identity, and Place,” Human Geography 30, no. 5 (2006), 627.

6. Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (New York: Routledge, 2002), 68.

7. Angela McRobbie, Feminism and Youth Culture: From Jackie to Just Seventeen (New York: MacMillian, 1991).

8. Stephen Duncombe and Maxwell Tremblay, eds., White Riot: Punk Rock and the Politics of Race (London: Verso, 2011).

9. Michelle Habell-Pallan, Loca Motion: The Travels of Chicana and Latina Popular Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 173.

10. Lucy Robinson, et. al, “Introduction: Making a Difference by Making a Noise,” in Youth Culture and Social Change: Making a Difference by Making a Noise (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2017), 10.

11. Monica Perales, Smeltertown: Making and Remembering a Southwest Border Community (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 267.

12. Kathleen Staudt, Violence and Activism at the Border: Gender, Fear, and Everyday Life in Ciudad Juárez (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008), 81.

13. Teresa Rodriguez and Diana Monatné with Lisa Pulitzer, The Daughters of Juárez: A True Story of Serial Murder South of the Border (New York: Atria Books, 2007), 92.

14. Staudt, Violence and Activism at the Border, 2.

15. Timothy Dunn, Blockading the Border: The El Paso Operation that Remade Immigration Enforcement (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010), 59.

16. Rachel Weiner, “Rep. Silvestre Reyes (D-Texas) Defeated By Beto O’Rourke,” Washington Post, May 30, 2012.

17. Quoted in David A. Ensminger, Visual Vitriol: The Street Art and Subcultures of the Punk and Hardcore Generation (Jackson: University of Mississippi, 2011), 107.

18. Fugazi, “Target,” 1995, track ten on Red Medicine, Dischord Records.

19. Erica Ortegón, Facebook Messenger conversation with author, April 2020.

20. Ensminger, Visual Vitriol, 109.

21. Jim Ward, interview, “Life is to Live,” published April 21, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jt5HjLyqqjk

22. Ernesto Ybarra, interview by author, December 2019.

23. Heimer, interview, January 2019.

24. Michael Morales, interview by author, December 2019.

25. Michael Morales, text conversation with author, May, 2020.

26. See Michael Kimmel, Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men, Understanding the Critical Years Between 16 and 26 (New York: HarperCollins, 2018) and Niobe Way, Deep Secrets: Boys’ Friendships and the Crisis of Connection (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2011).

27. Jessica Flores, interview by author, January 2020.

28. Ernesto Ybarra, interview by author, December 2019.

29. Jason Cagann, interview by author, April 2020.

30. Erik Frescas, interview by author, April 2020.

31. Erica Ortegón, interview by author, January 2020.

32. Luis Mota, interview by author, January 2020.

33. Mundo, interview by author, April 2020.

34. El Paso Punk zine from the personal collection of Fill Heimer.

35. Book Your Own Fuckin’ Life, Vol. 4 (1994).

36. “Episode 185—Cedric Bixler-Zavala (At the Drive-In, the Mars Volta, Foss, Antemasque, Anywhere, De Facto etc)” September 18, 2018, in Turned out a Punk Podcast, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/footnote-185-cedric-bixler-zavala-at-drive-in-mars/id940288964?i=1000420340549.

37. Chris Banta, interview by author, January 2020.

38. Jenny Cisneros, interview by author, April 2020.

39. Marrisa López, “¿Soy emo y Qué?: Sad Kids, Punkera Dykes, and the Latin@ Public Sphere,” Journal of American Studies, 46, no. 4 (2012), 900.

40. Fill Heimer, David Lucey, Ernesto Ybarra, and Michael Morales, text conversation with author, February 2020.

41. Fixed Idea, “Chucotown,” 1996, track B2 on “Chuco Town” 7” EP. Permission to reproduce lyrics to “Chucotown” given by Fill Heimer to author, April 21, 2020.

42. Morales, interview, December 2019.

43. Ybarra, interview, December 2019.

44. Flores, interview, January 2020.

45. Morales, interview, December 2019.

46. Perales, Smeltertown, 48-50.

47. Gerardo Licón, “Pachucas, Pachucos, and Their Culture: Mexican American Youth Culture of the Southwest, 1910-1955” (PhD Diss., Department of History, University of Southern California, 2009), 79.

48. Ibid., 32.

49. Morales, interview, December 2019. See also Alex Durán, “Steppin’ Out with Cedric of Antemasque,” Fusion, May 20, 2015.

50. Howard S. Becker, “Art as Collective Action,” American Sociological Review 39, no. 4, December 1974, 767.

51. American Fact Finder, US Census Bureau. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml?src=bkmk. The author gathered poverty rates from two zip codes, 79907 and 79915, the zip codes of the Ysleta, Del Valle, and Bel Air High Schools, which Lower Valley punks attended.

52. Habel-Pallán, Loca Motion, 150.

53. Ybarra, interview, December 2019.

54. Book Your Own Fucking Life, Vol. 4.

55. Morales, interview, December 2019.

56. Ybarra, interview, December 2019.

57. Morales, text conversation, April 2020.

58. Erica Ortegón, interview with author, March 2020.

59. Erica Ortegón, Facebook Messenger conversation with author, May 2020.

60. Oretgón, interview, January 2020.

61. Ortegón, interview, January 2020. Candy From Strangers zine, issue #3. From the personal collection of Erica Ortegón.

62. Ortegón, interview, March 2020.

63. Eric Klinenberg, Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life (New York: Crown, 2018), 5.

64. Frescas, interview, April 2020.

65. Heimer, interview, January 2020.

66. Cisneros, interview, April 2020.

67. Barry Shank, Dissonant Identities: The Rock n’ Roll Scene in Austin, Texas (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1994), xiv.

68. David Lucey, interview by author, January 2020.

69. El Paso Punk zine. From the personal collection of Fill Heimer.

70. American Fact Finder, US Census, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml?src=bkmk. Author used poverty rates in zip code 79912.

71. Mota, interview, January 2020. See also Maribel Sanotoyo, “Show reunites Bands from ‘80s, ‘90s El Paso punk scenes,” What’s Up, December 15, 2010, https://whatsuppub.com/music/article_e63a)b17-8bf4-5719-aee1-1c16d23b9c56.html.

72. Flores, interview, January 2020.

73. Jessica Flores, interview by author, April 2020.

74. McRobbie, Feminism and Youth Culture, 25.

75. Flores, interview, April 2020.

76. Cisneros, interview, April 2020.

77. Alex Martinez, interview by author, May 2020.

78. Martinez, interview, May 2020.

79. Flores, interview, April 2020.

80. Martinez, interview, May 2020.

81. Cagann, interview, April 2020.

82. Quoted in “Two UT El Paso Students Die in Car Accident,” The Prospector. March 25, 1997.

83. Crystal Robert, untitled article on Sarah Reiser and Laura Beard, accessed May 1, 2020, https://atd-i.tumblr.com/post/164851273/sarahreiser-left-and-laura-beard-prospector.

84. “Two UT El Paso Students Die in Car Accident,” The Prospector, March 25, 1997.

85. Ibid.

86. Cagann, interview, April 2020.

87. At the Drive-In, “Napoleon Solo,” 1998, track four on In Casino/Out, Fearless Records.

88. Robinson, et. al, “Introduction,” 10.

89. “El Paso Population,” World Population Review, https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/el-paso-tx-population. “Ciudad

Juárez,” Population City, https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/ciudad-juarez-population.

90. “El Paso Stays Low in Crime Stats,” El Paso Inc., October 31, 2016, http://www.elpasoinc.com/news/local_news/el-paso-stays-low-in-fbicrime-stats/article_90e2750c-9f7e-11e6-9d3f-ef1d0f1c3564.html.

91. “Juárez Among the 50 Most Dangerous Cities in the World,” El Paso Times, July 17, 2018, https://www.elpasotimes.com/story/news/world/2018/07/17/juarez-50-most-dangerous-cities-world/791543002/.

92. Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands: La Frontera, The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Anne Lute Books, 1987; 2007), 25.

93. Quoted in Sanotoyo, “Show reunites Bands from ‘80s, ‘90s El Paso punk scenes.”

94. Ed Ivey, interview by author, December 2019.

95. Mundo, interview, April 2020.

96. Ibid.

97. Frescas, interview, April 2020.

98. Book Your Own Fuckin' Life, Vol. 5 (1996), https://archive.org/stream/byofl_5/byofl_5_djvu.txt.

99. Frescas, interview, April 2020.

100. Mundo, interview, April 2020.

101. Ibid.

102. Ibid.

103. “Revolución X en Imperdibles,” NOESFM, podcast, March 27, 2017.

104. Gaspar Orozco, interview by author, May 2020.

105. Revolución X, “I’m Making my Future with the Border Patrol,” track B2 on “Revolución X” 7” EP, 1994. Lyrics reprinted with permission from Gaspar Orozco.

106. Cagann, Interview, April 2020.

107. Patricia Zavella, “Beyond the Screams: Latino Punkeros Contest Nativist Discourses,” Latin American Perspectives, Vol. 39, no. 2, (2012), 37.

108. Orozco, interview, May 2020.

109. Dunn, Blockading the Border, 38.

110. Steven S. Volk & Marian E. Schlotterbeck, “Gender, Order, and Femicide: Reading the Popular Culture of Murder in Ciudad Juárez,” Aztlan 32, no. 1 (2007), 59.

111. Staudt, Violence and Activism at the Border, 69.

112. Julia Monárrez Fragoso, “Feminicidio sexual serial en Ciudad Juárez: 1993-2001,” Debate Feminista 25, (April 2002), 283.

113. Staudt, Violence and Activism at the Border, 99-100.

114. Quoted in Judith Matloff, “Six women murdered each day as femicide in Mexico nears a pandemic,” Al Jazeera American, January 4, 2015.

115. Fragoso, “ Feminicidio sexual serial en Ciudad Juárez,” 283.

116. Perales, Smeltertown, 261.

117. At the Drive-In, “Invalid Litter Dept.,” 2000/2013, track five on Relationship of Command, Twenty-First Chapter Records.

118. Rodríguez, The Daughters of Juárez, 102-103.

119. At the Drive-In, “Invalid Litter Dept.,” posted November 10, 2006, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0ozn8DsNGc.

120. Morales, interview, December 2019.

121. Orozco, interview, May 2020.

122. Quoted in Perales, Smeltertown, 259.

123. Licón, “Pachucas, Pachucos, and Their Culture,” 109.

124. Ybarra, interview, December 2019.

125. Cagann, interview, April 2020.

126. Cisneros, interview, April 2020.

127. Heimer, interview, January 2020.

128. Quoted in Perales, Smeltertown, 46.

129. George Lipsitz, “Buscando America (Looking for America): Collective Memory in an Age of Amnesia,” in Time Passages: Collective Memory and American Popular Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990), 260.

130. George Lipsitz, “History, Myth, and Counter-Memory: Narrative and Desire in Popular Novels,” in Time Passages: Collective Memory and American Popular Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990), 212.

131. At the Drive-In, “One Armed Scissor,” 2000/2013, track three on Relationship of Command, Twenty-First Chapter Records.